THE BASS LINES OF PAUL SIMON’S GRACELAND

By

CHARLES S. DEVILLERS

A RESEARCH PAPER

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Music in Commercial Music

in the School of Music

of the College of Visual and Performing Arts

Belmont University

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

May 2020

ii

Submitted by Charles S. DeVillers in partial fulfillment of the requirements for

the degree of Master of Music in Commercial Music.

Accepted on behalf of the Graduate Faculty of the School of Music by the

Mentoring Committee:

_______________ ______________________________

Date Roy Vogt, M.M.

Major Mentor

______________________________

Bruce Dudley, D.M.A.

Second Mentor

______________________________

Peter Lamothe, Ph.D.

Third Mentor

_______________ ______________________________

Date Kathryn Paradise, M.M.

Assistant Director, School of Music

iii

Contents

Examples ............................................................................................................................ iv

Presentation of Material

Introduction ..............................................................................................................1

Chapter One: An Overview of Paul Simon’s Graceland.........................................3

Chapter Two: Bakithi Kumalo and South African Township Music ....................14

Chapter Three: Elements of South African Music Within the Bass Lines of

Graceland ..............................................................................................................22

Chapter Four: The Bass in Paul Simon’s Post-Graceland Material ......................44

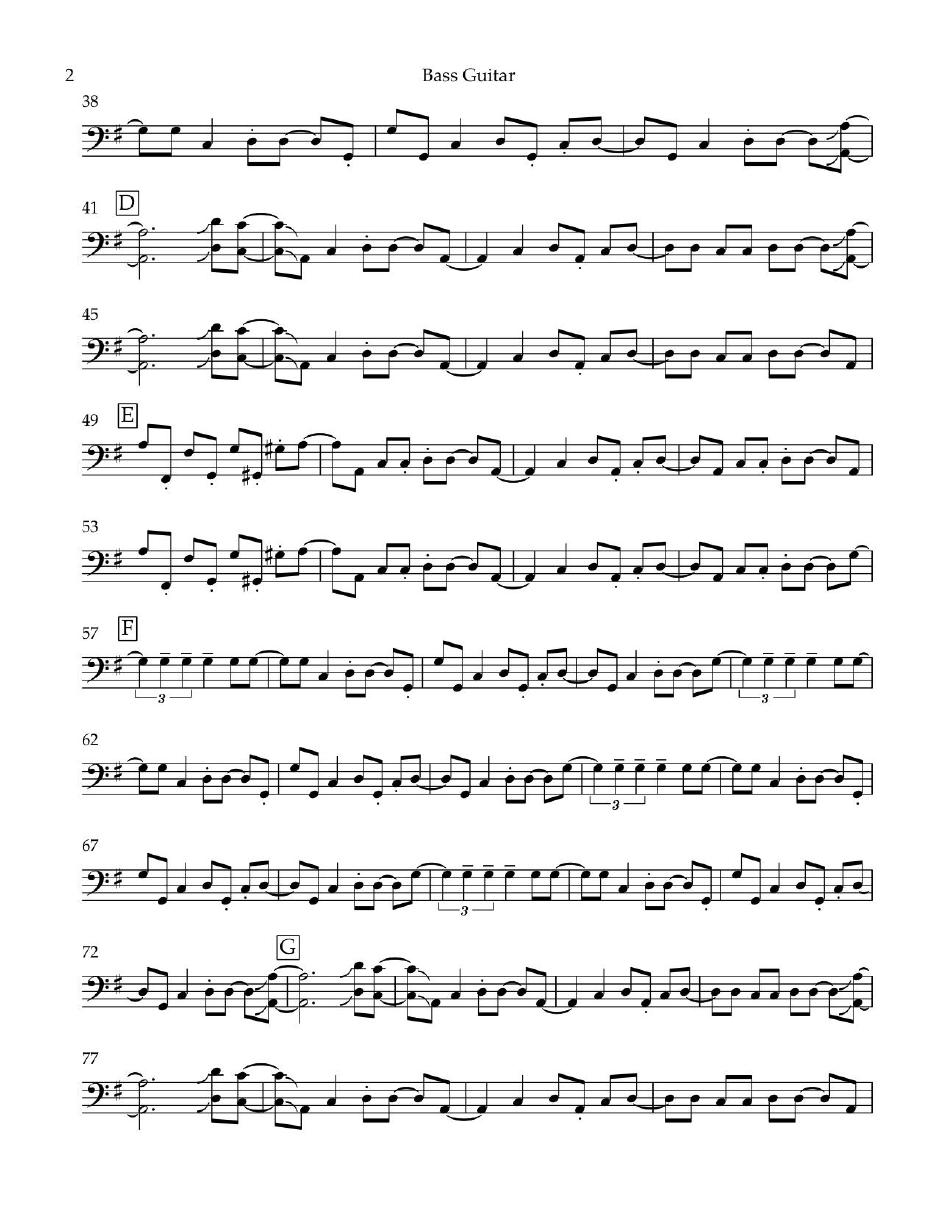

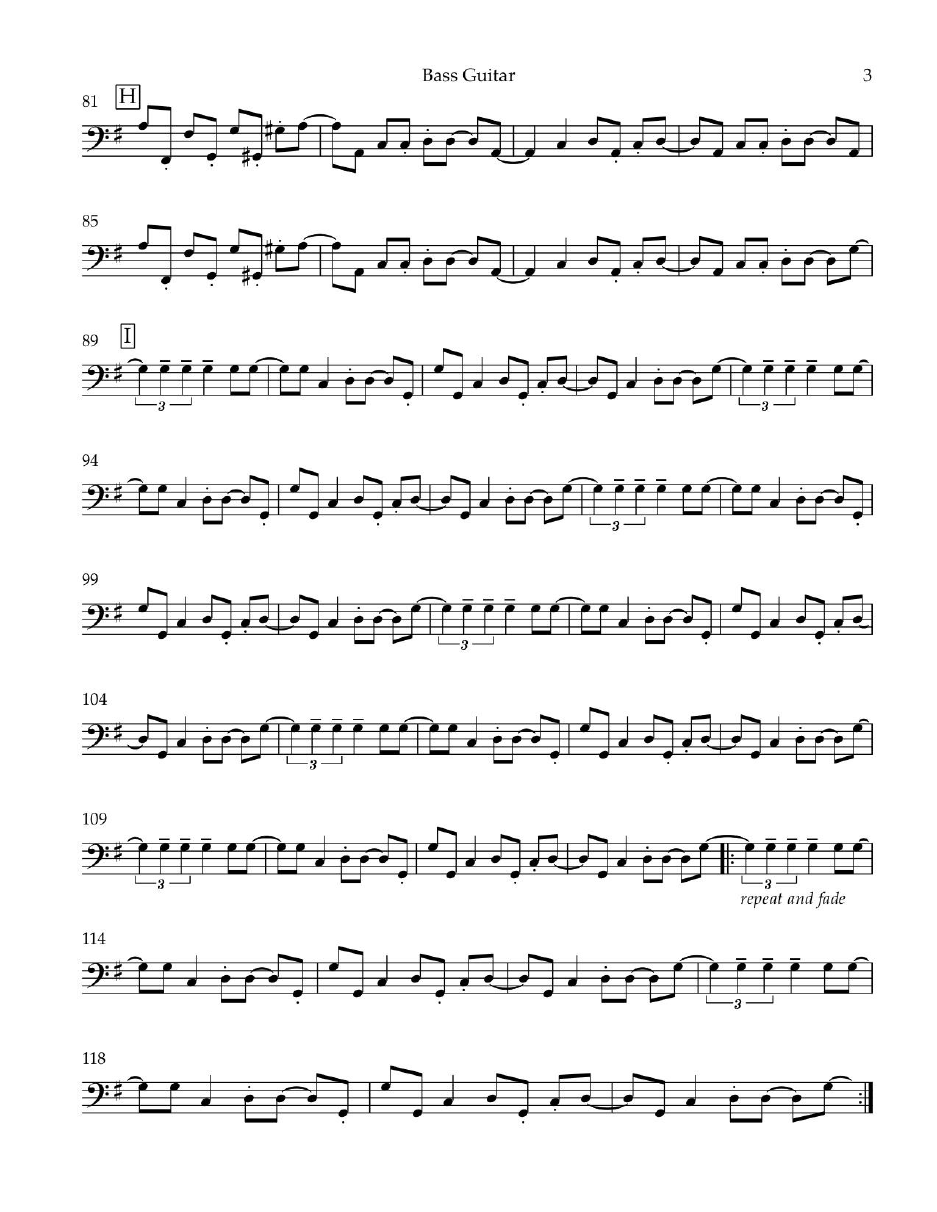

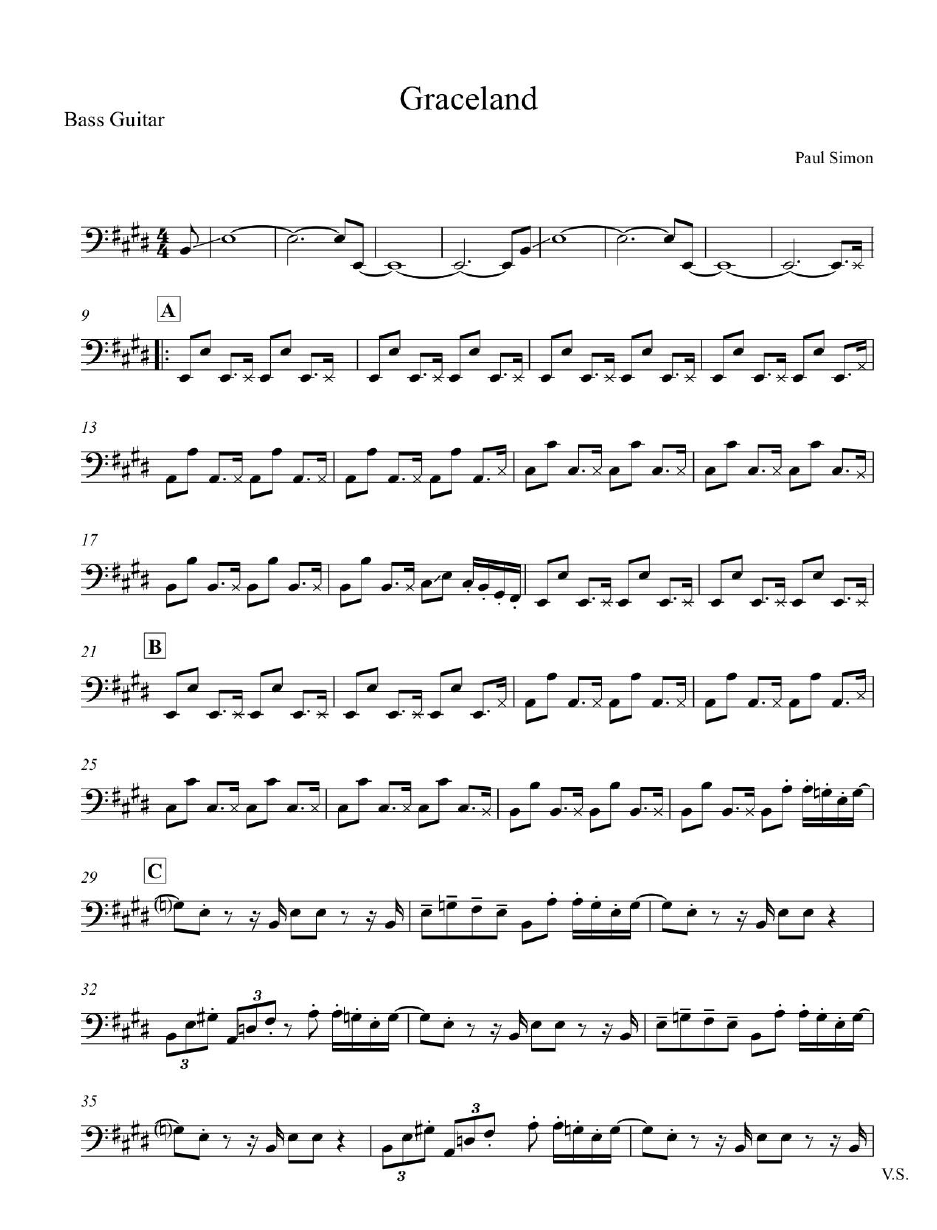

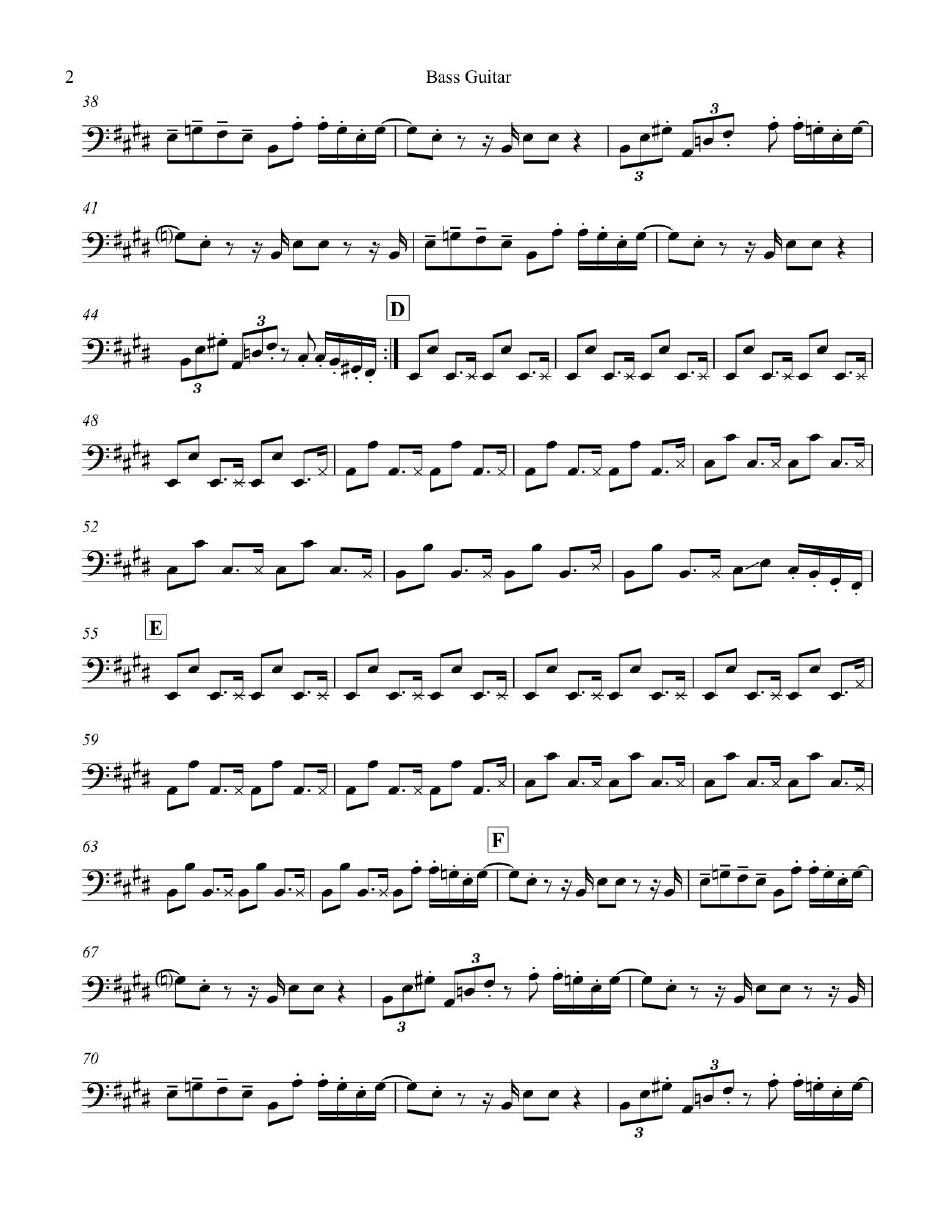

Appendix: Full Transcriptions ...........................................................................................54

References ..........................................................................................................................79

iv

Examples

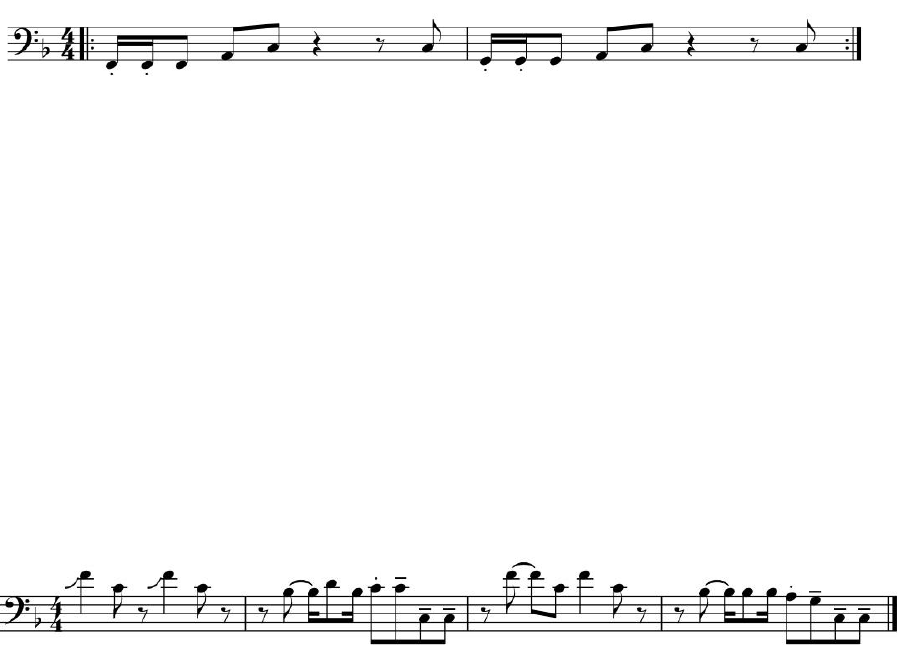

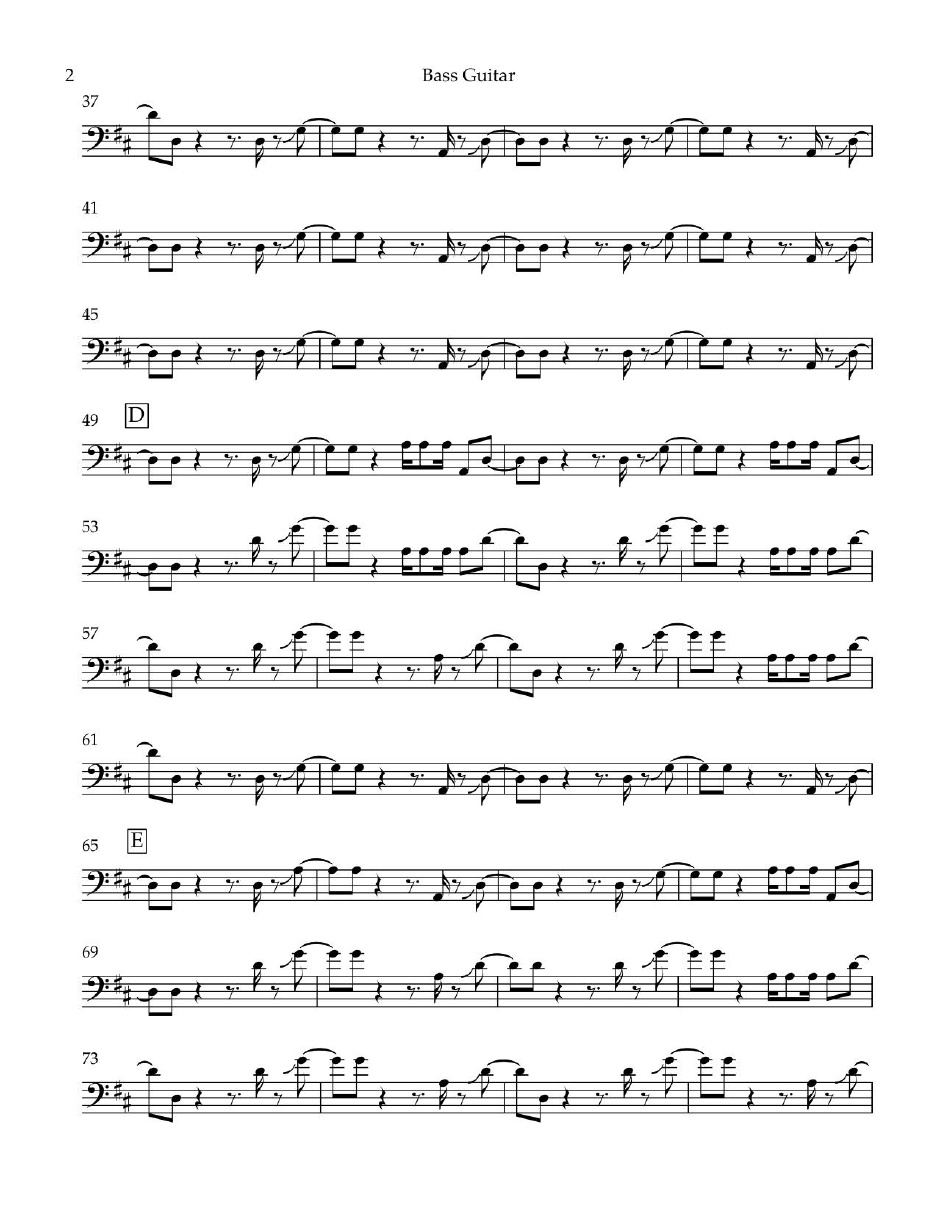

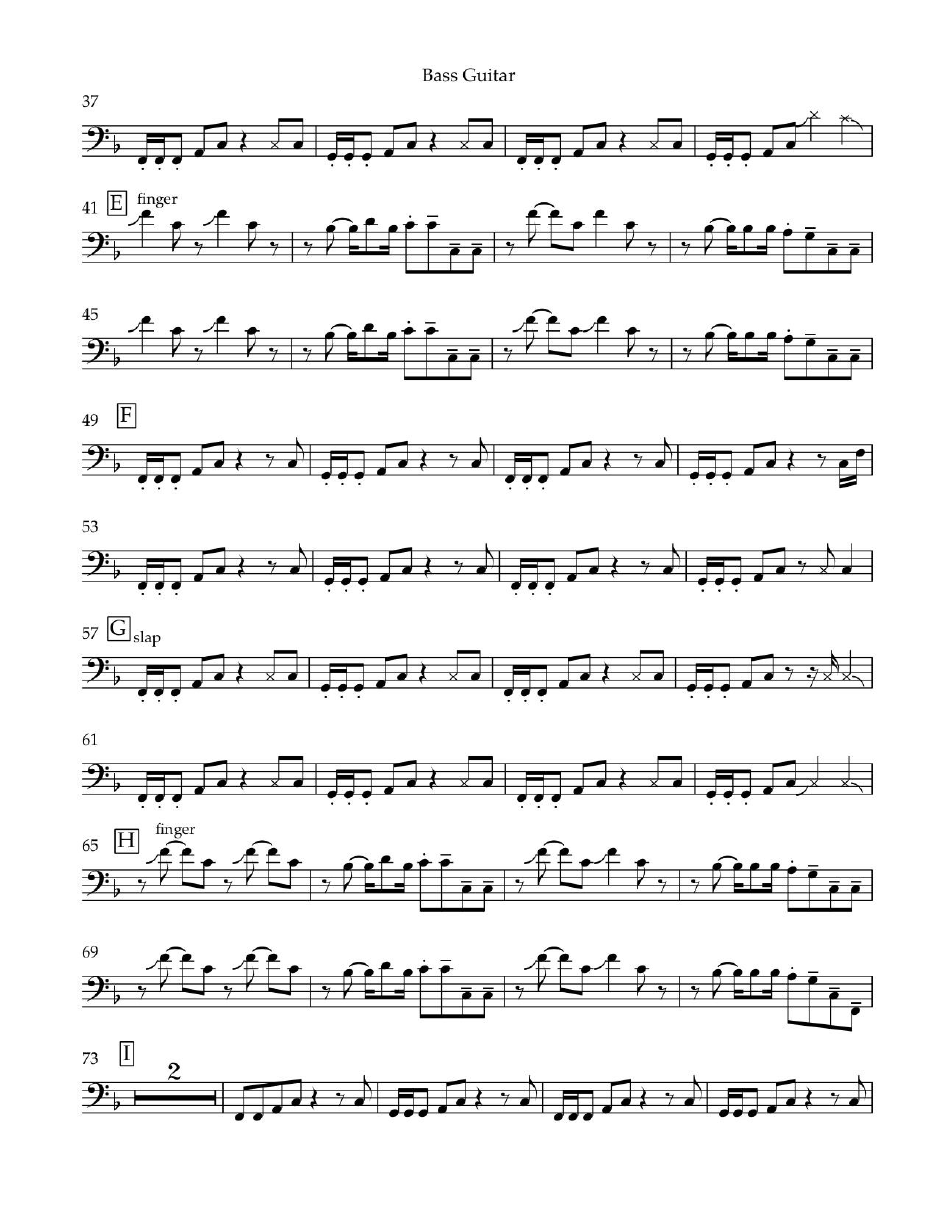

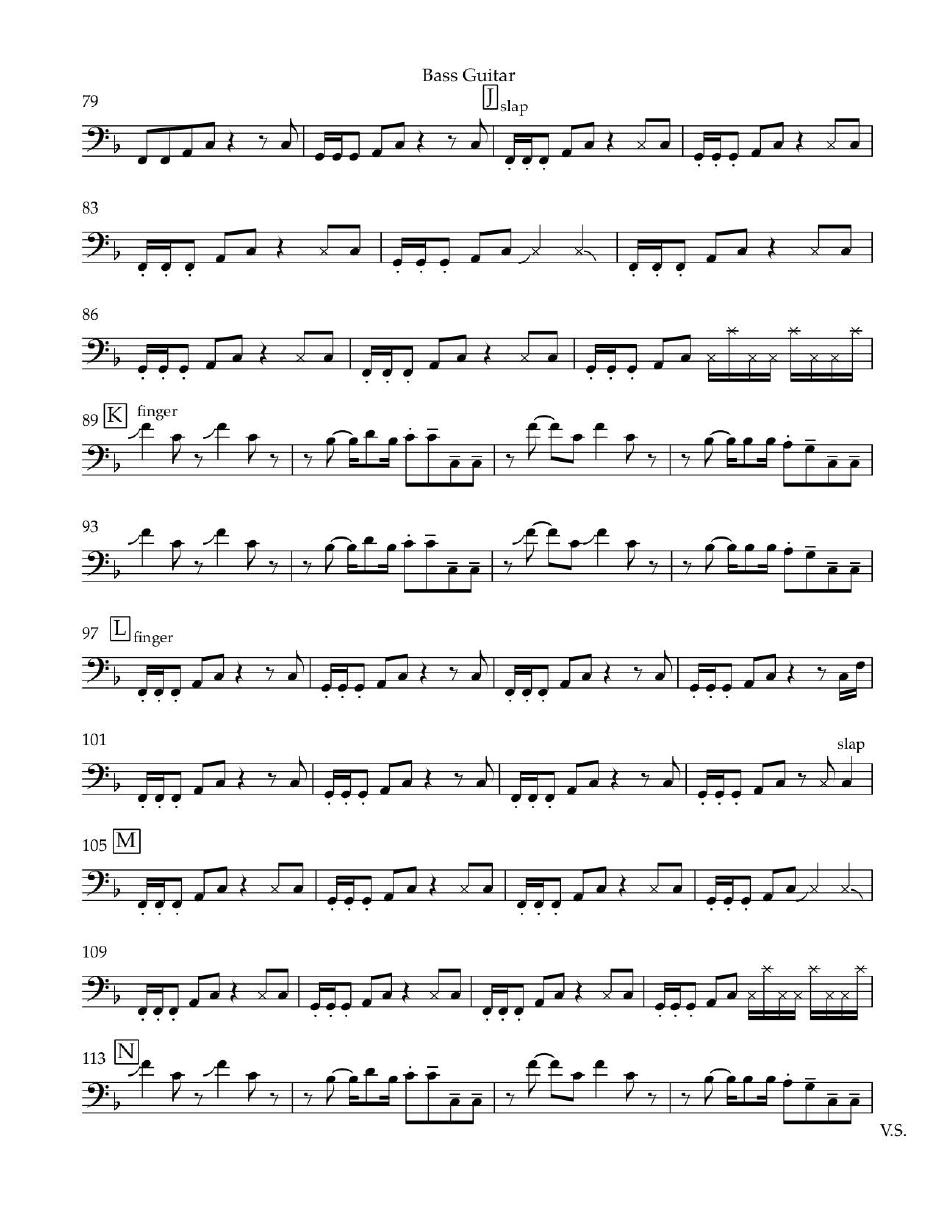

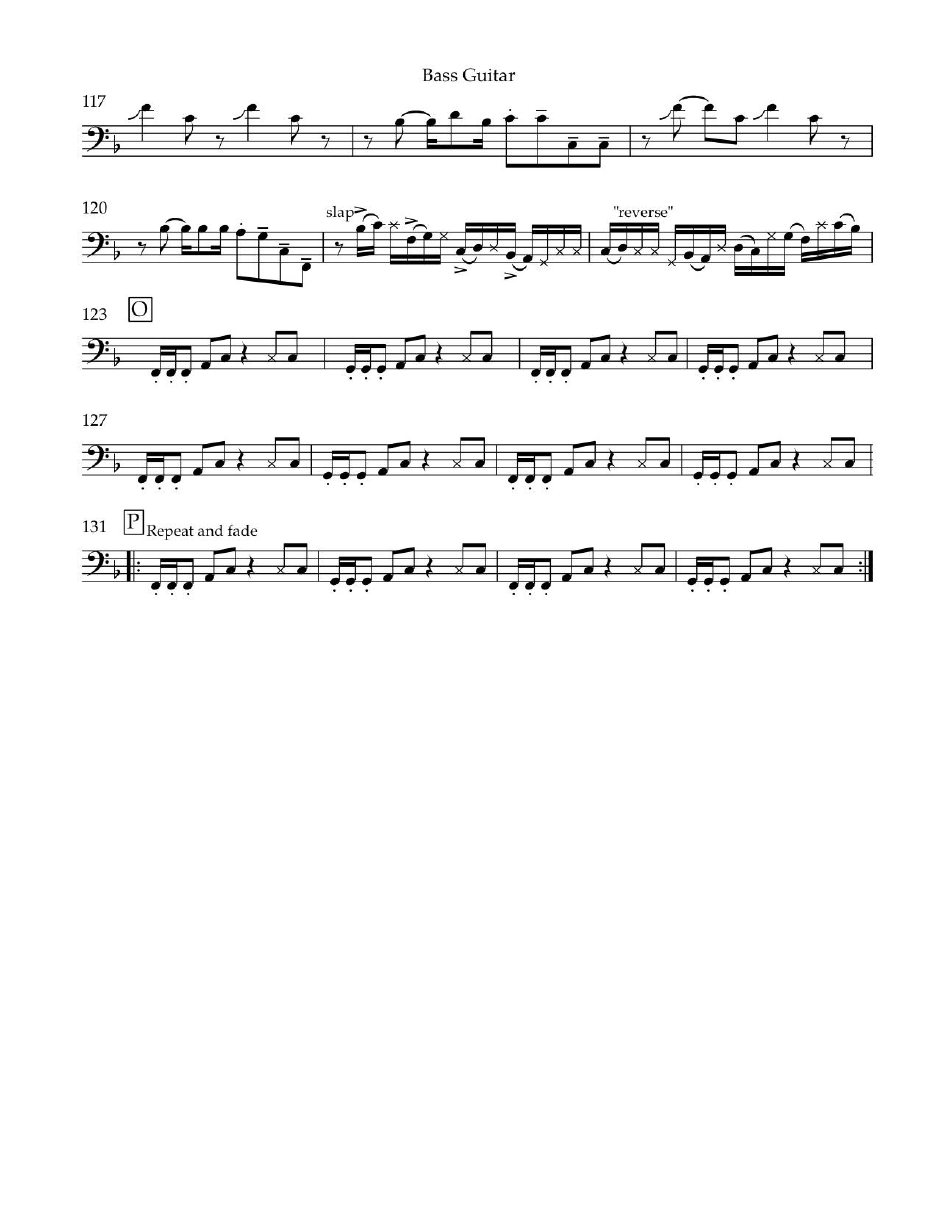

3.1 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 9-12 .....................................................................29

3.2 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 25-28 ...................................................................30

3.3 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 41-44 ...................................................................30

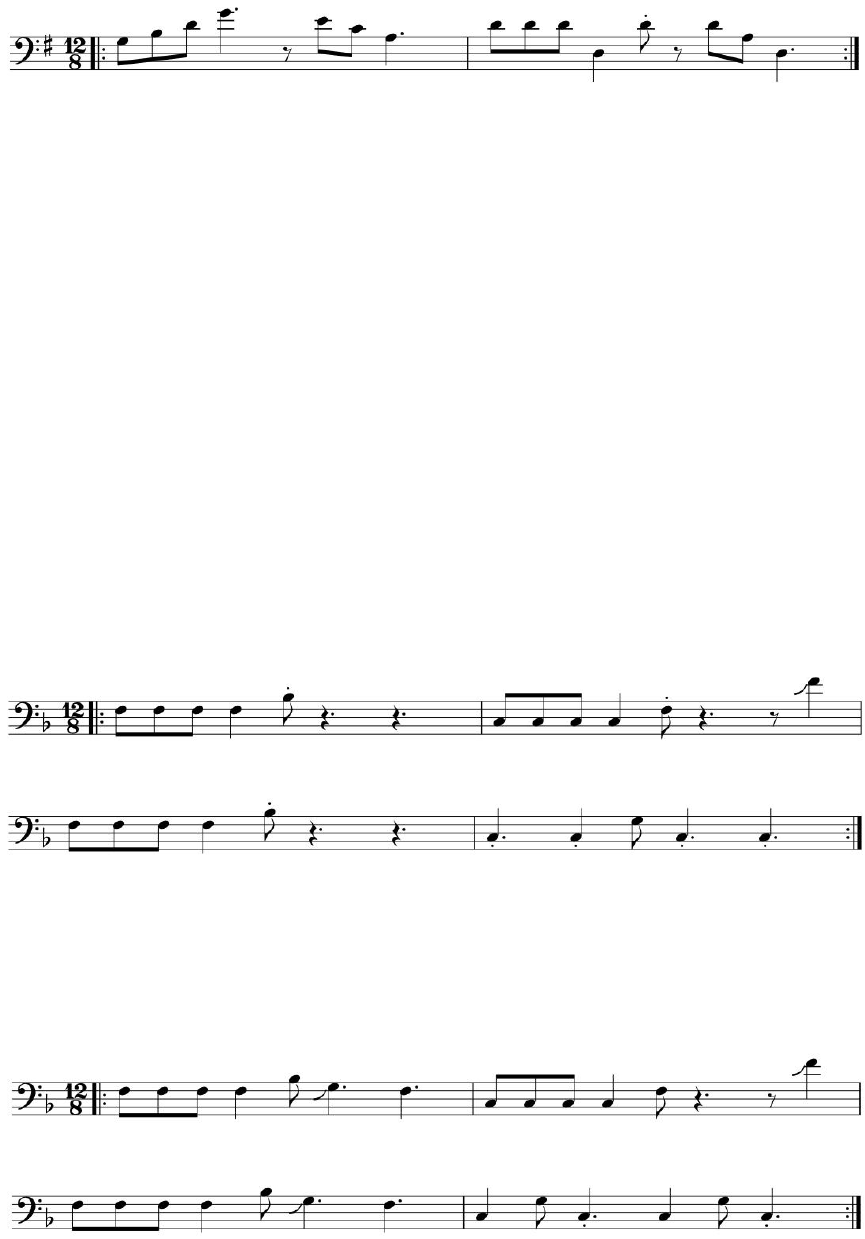

3.4 “Graceland” measures 9-16 .........................................................................................31

3.5 “Graceland” measures 28-32 .......................................................................................33

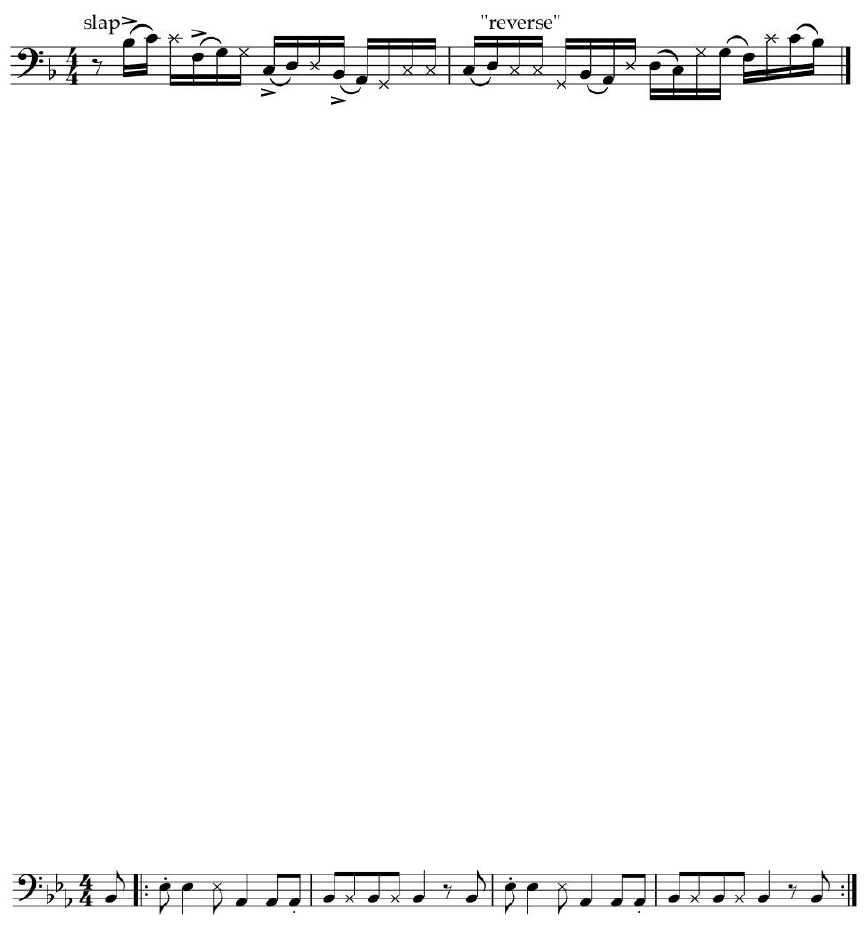

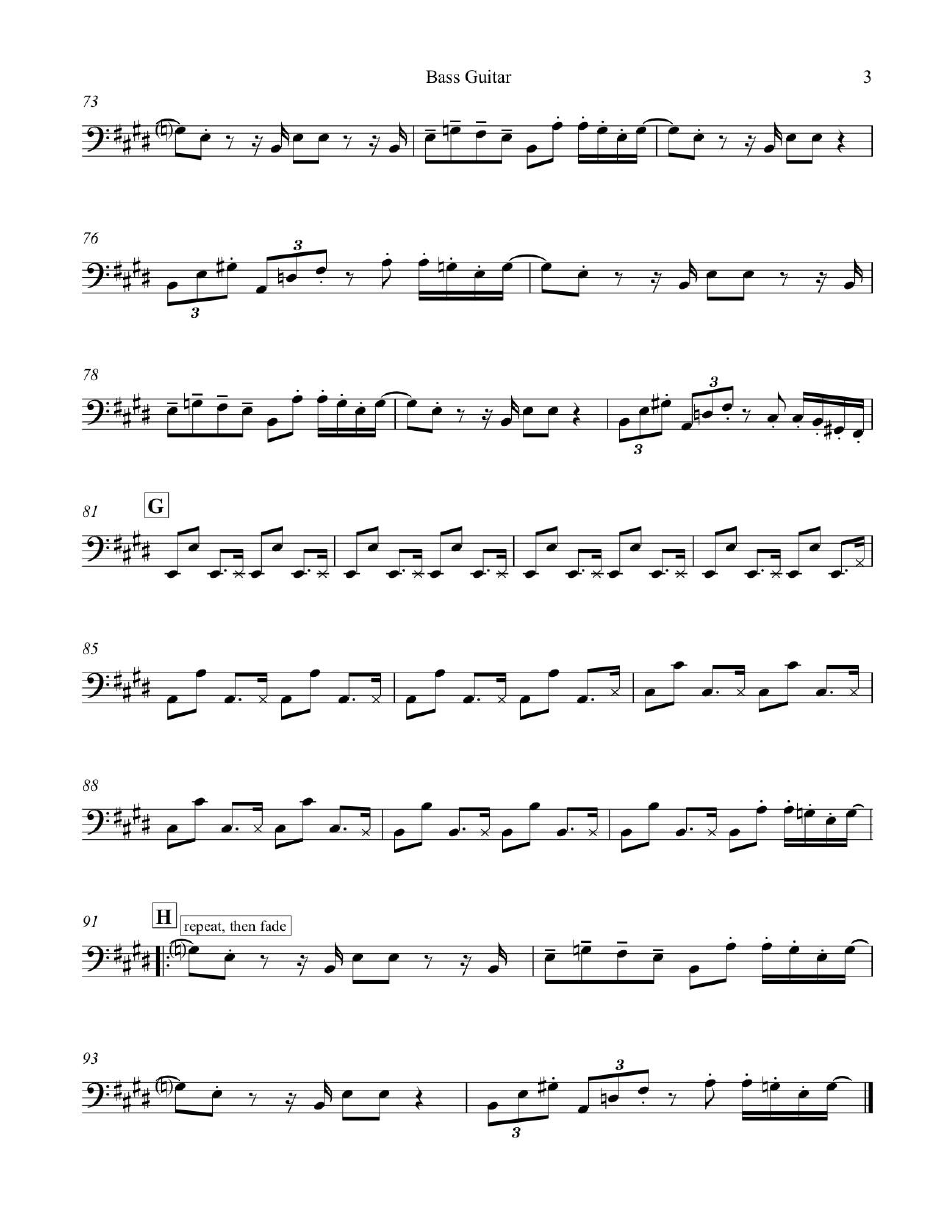

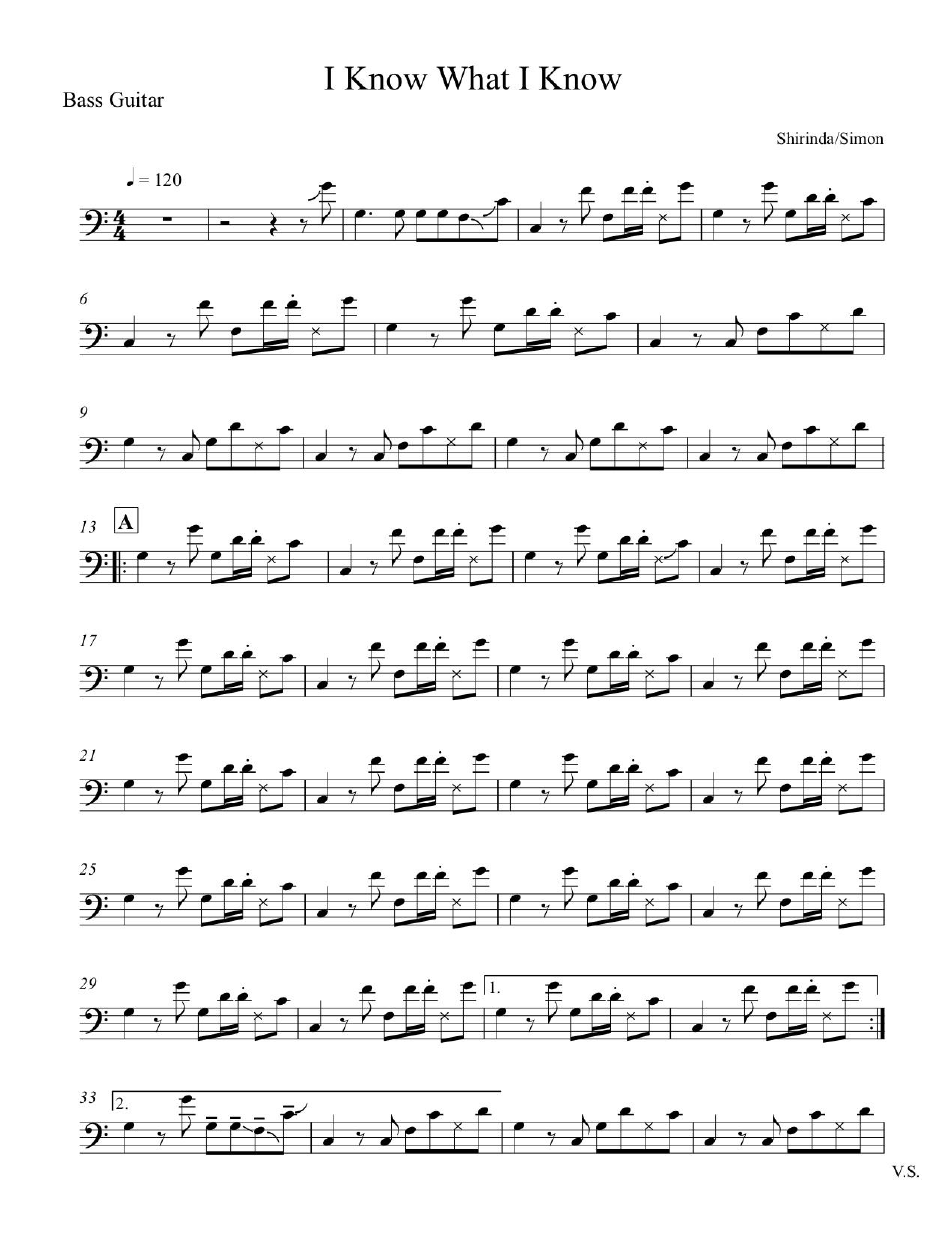

3.6 “I Know What I Know” measures 3-5 .........................................................................33

3.7 “I Know What I Know” measures 8-9 .........................................................................33

3.8 “Gumboots” measures 3-7 ...........................................................................................34

3.9 “Gumboots” measures 13-17 .......................................................................................35

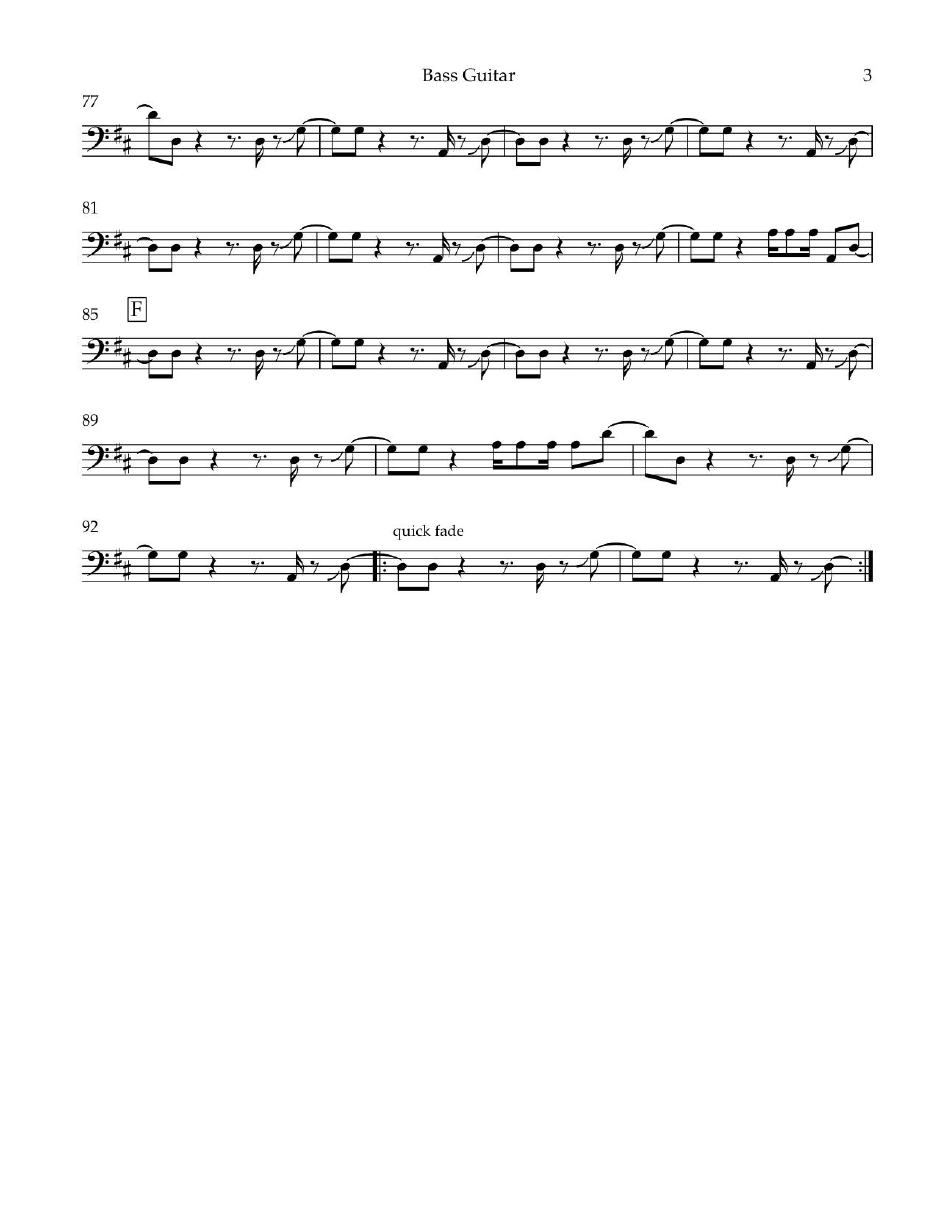

3.10 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 1-3 ...............................................36

3.11 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 17-18 ...........................................36

3.12 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 25-27 ...........................................37

3.13 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 35-43 ...........................................37

3.14 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 3-4 ........................................................................38

3.15 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 17-20 ....................................................................38

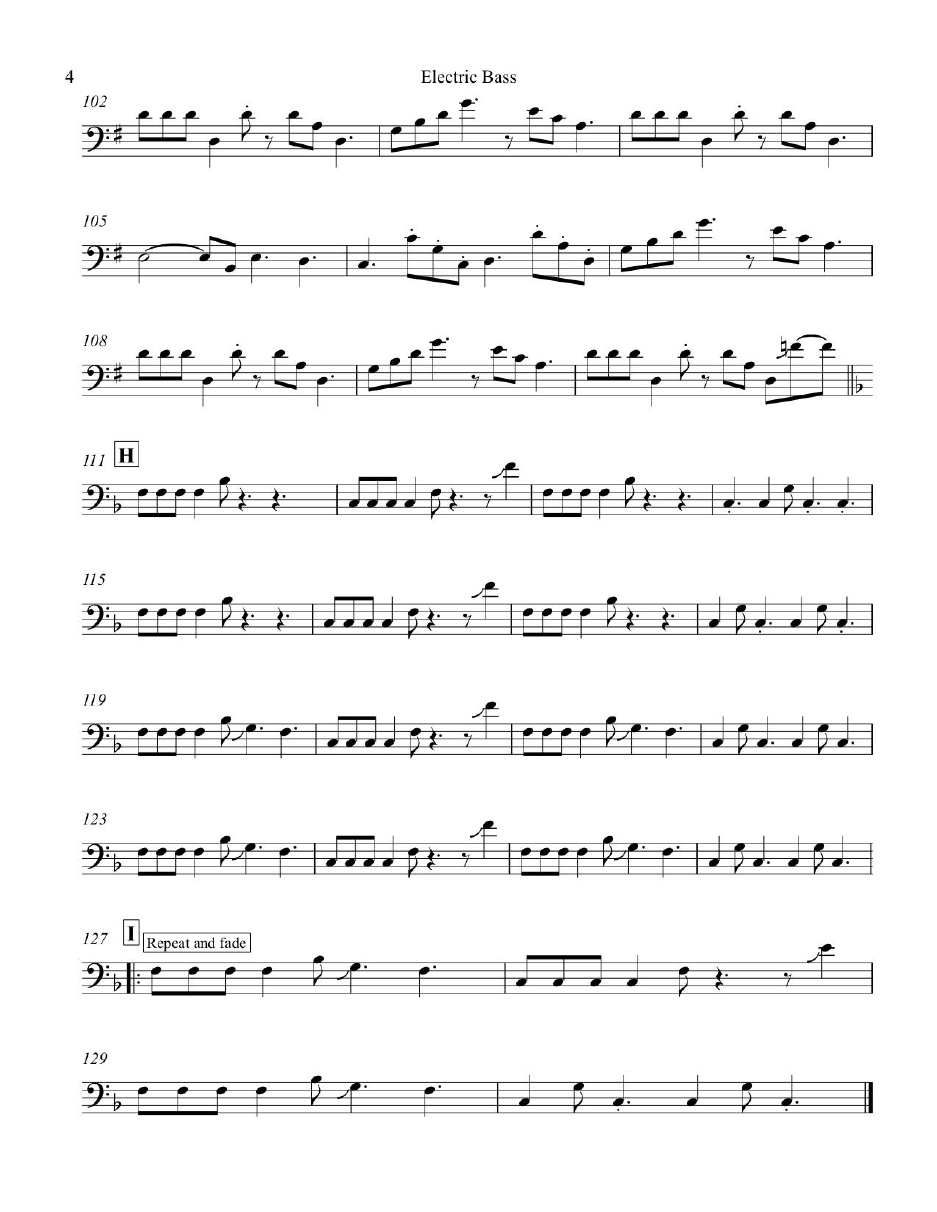

3.16 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 122-123 ................................................................39

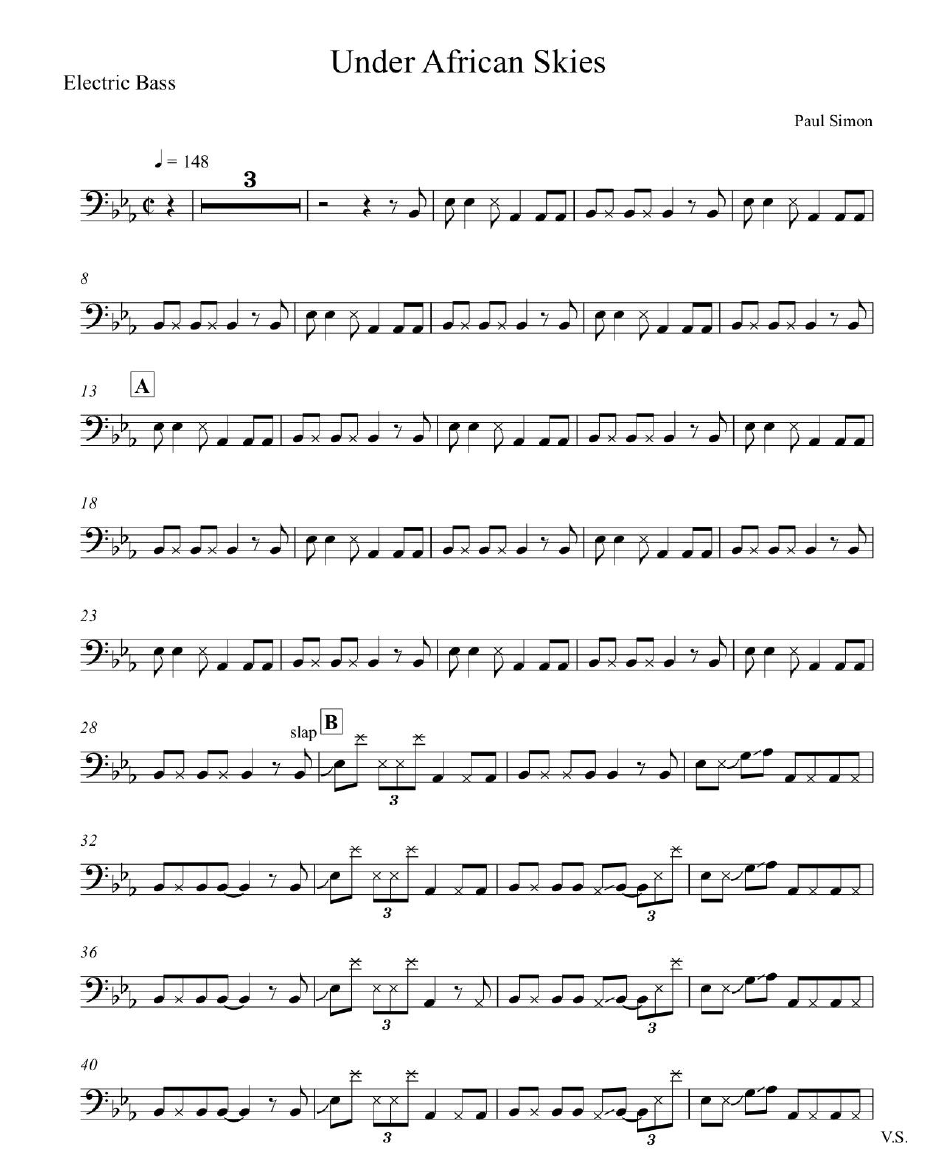

3.17 “Under African Skies” measures 5-8 .........................................................................39

3.18 “Under African Skies” measures 29-32 .....................................................................40

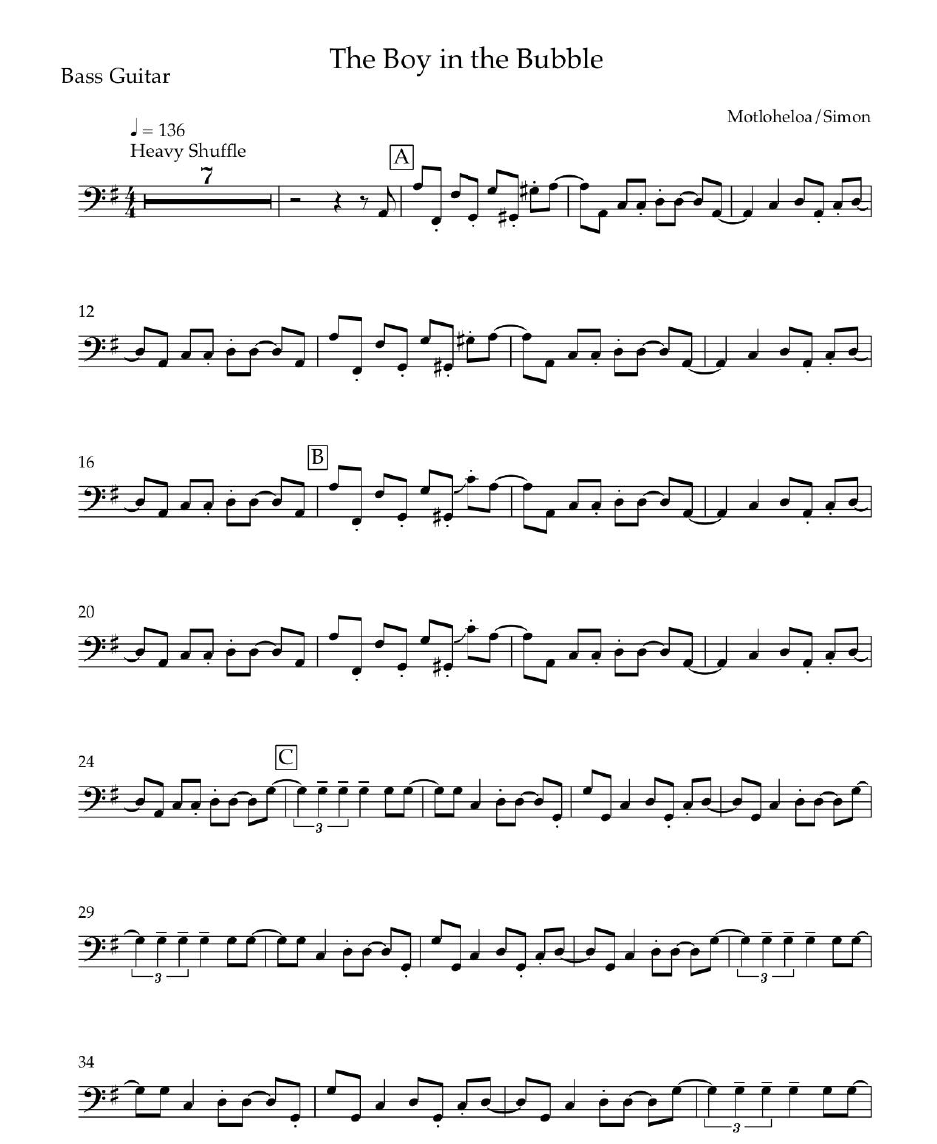

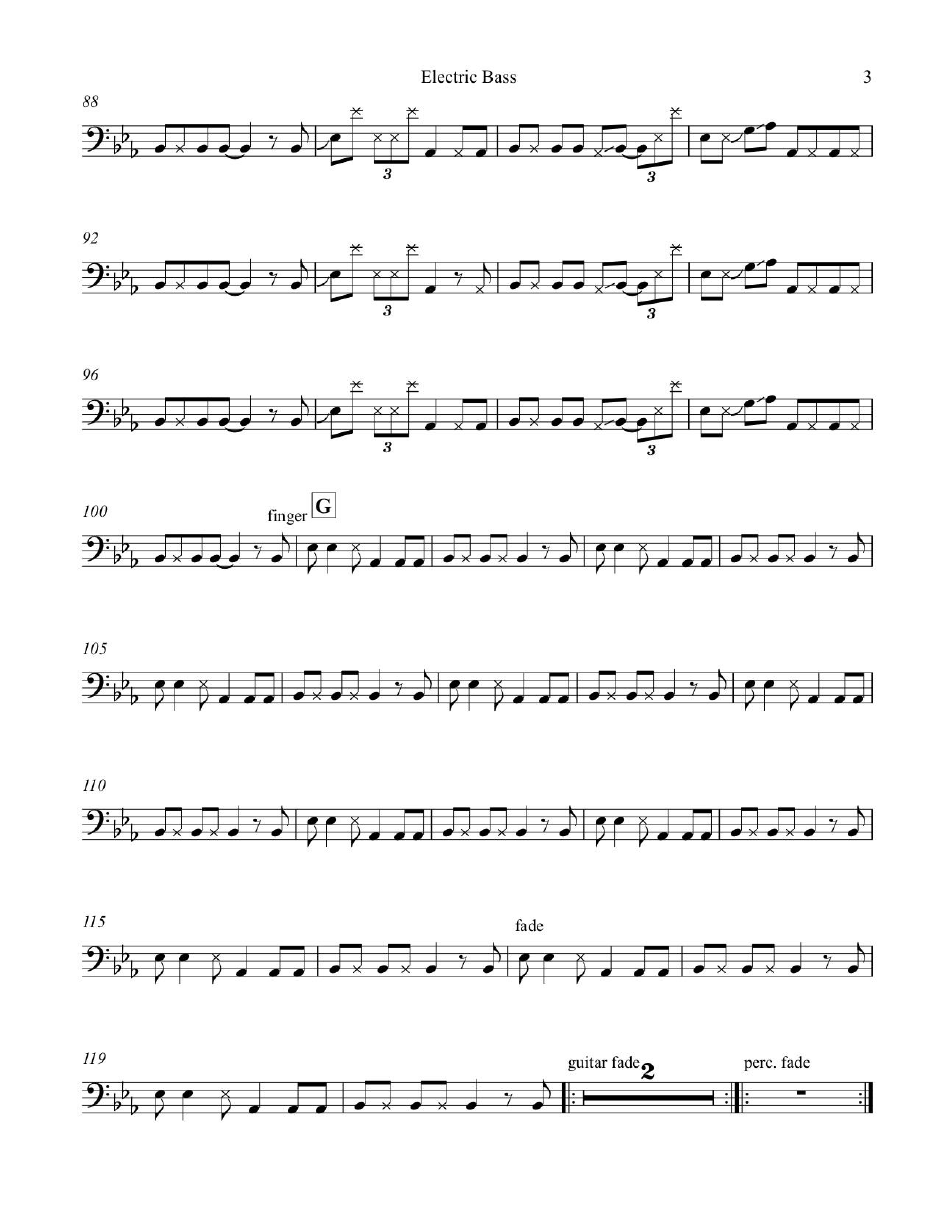

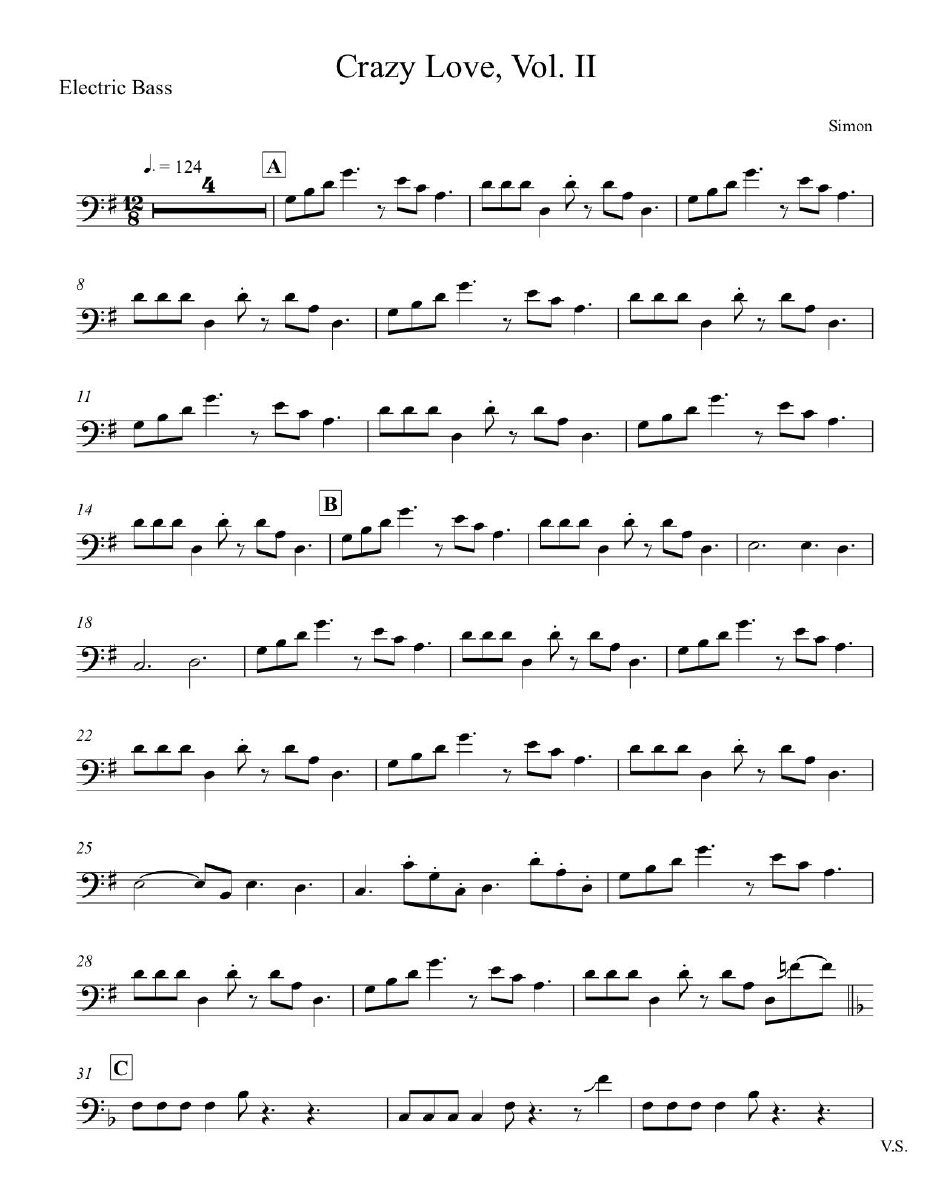

3.19 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 5-6 ..........................................................................41

v

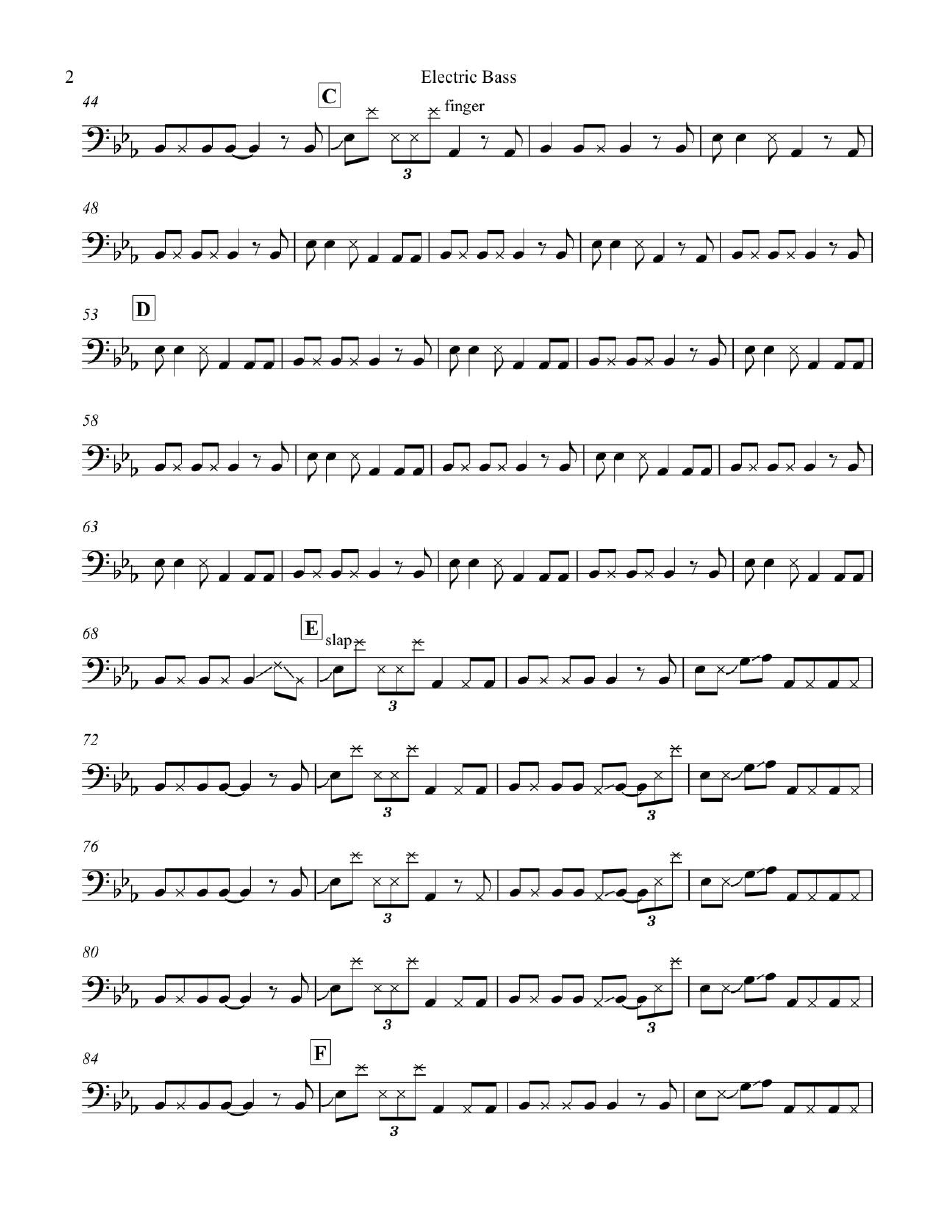

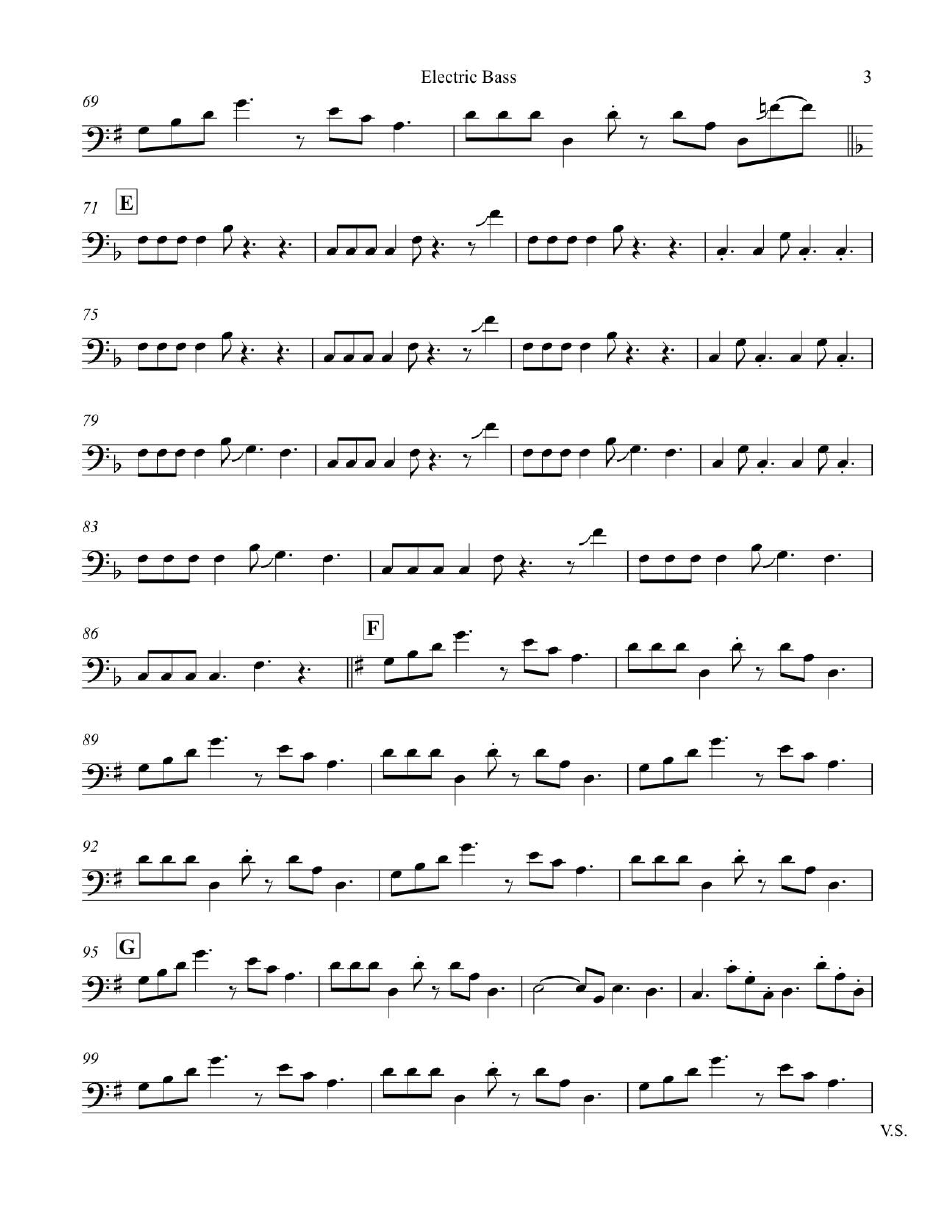

3.20 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 31-34 ......................................................................41

3.21 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 79-82 ......................................................................42

1

Introduction

Paul Simon’s 1986 album Graceland is considered by many to be a highlight of

the renowned American songwriter’s career, including Simon himself who cites it as “the

most significant achievement in my career” (Berlinger 2012). Even upon its release, the

album was seen as a high point in the singer’s catalog, and an instant classic, as is noted

in a 1986 Spin review that calls the album “Paul Simon’s greatest work” (O’Brien 1986,

27). Often praised for its groundbreaking combination of South African music with

American pop by fans and critics alike, the core of what makes Graceland such an

interesting album is the way in which Simon incorporates these two styles to create a

unique sound. Part of what makes this combination successful was Simon’s use of South

African session musicians during the recording process, who add authenticity to the

album’s fusion of genres. Among these session musicians was bassist Bakithi Kumalo,

whose fretless bass playing lends itself to many iconic moments on the album, as well as

provides a unique backbone to the album’s fusion of sounds and styles.

The goal of this project will be to identify ways in which elements of South

African music present within the bass lines combine with Simon’s American pop

songwriting to create a sound that is unique to Graceland, and which further influenced

Simon’s songwriting later in his career. In order to achieve this, the first chapter of this

paper will focus on the origin of the Graceland project, how it was initially

conceptualized, and how, where, and when the recording sessions occurred. This

2

information will provide a background to further contextualize the ways in which South

African and American musical elements are combined on the record. The second chapter

will focus on the background of Bakithi Kumalo and the styles of South African music he

plays and is influenced by to provide context for the styles of bass playing on the album.

Chapter Three will present analyses of the bass lines and identify elements of traditional

and popular South African music within them. Finally, by focusing on how the role of

these bass lines affect the overall sound of Graceland, and by looking at how the electric

bass is involved in Simon’s post-Graceland instrumental arrangements, the last chapter

will demonstrate how the bass lines of Graceland contributed to a change in how Simon

utilized the instrument during the later years of his career.

3

Chapter One:

An Overview of Graceland

The story of Paul Simon’s Graceland is described in the book Paul Simon:

American Tune as “such a perfect piece of pop mythology that the idea that it all actually

happened tends to get lost in the folklore” (Bonca 2015, 100). The beginnings of what

would become Graceland can be traced to events happening in Simon’s career and

personal life throughout the early 80s. By 1983, Simon was about to release his second of

two critically underwhelming albums in a row, and as Cornel Bonca (2015, 100) put: “It

helps to remember that one of the things that freed Simon up to experiment with

something as foreign to him as African music was precisely that his career was in the

dumps.” Although his 1983 release Hearts and Bones was his first album not to be

certified gold, Simon’s troubles dated back even before the release of that album due to

increasing tensions within his personal life (Hilburn 2018, 246). Around the time Simon

was writing Hearts and Bones, he had begun seeing a psychiatrist to deal with negative

thoughts and anxiety surrounding financial troubles due to his previous album and movie

One Trick Pony, as well as tensions with former partner Art Garfunkel, and a short-lived

marriage and divorce with movie star Carrie Fisher (Carlin 2016, 252-53). Simon

himself “was so shaken when the album didn’t do better, especially coming after One

Trick Pony, that it made him question his ability to continue as a successful recording

artist” (Hilburn 2018, 246). Simon recalls by the time Hearts and Bones was released he

4

was exhausted, and didn’t do anything to promote the record which resulted in a flop

(Eliot 2010, 186).

As 1984 passed by, Simon did not know what to do next. He reportedly spent

days in Montauk watching the house he had planned for himself and his now ex-wife

Carrie Fisher being built and listening to tapes to pass the time (Hilburn 2018, 250-51).

One of the tapes Simon found himself returning to often was a bootleg mixtape called

Accordion Jive Hits Vol. 2, which was lent to him by fellow singer-songwriter Heidi Berg

(Carlin 2016, 277-78). It was on this mixtape that Simon heard the South African

township music that would become the basis for the Graceland’s sound. At this point in

Simon’s career, he felt that it was time to do something besides trying to get a typical pop

hit like on his previous records, and felt the freedom to “go by his instincts” as nobody

thought enough of him at that point to pressure him for a hit (Hilburn 2018, 250). After

listening to the tape several times, Simon realized that it was his favorite tape in his

collection, and found himself not wanting to listen to anything else (Berlinger 2012).

There was one song that Simon was especially interested in, and wanted to use as the

basis for his upcoming project. However, the only information he had was a title and

artist: “Gumboots” by The Boyoyo Boys. He enlisted the help of Warner Brothers

President Lenny Waronker, who had been successful in signing South African group

Juluka, to find a contact in South Africa to help him track down the music he was so

mesmerized by (Carlin 2016, 279). Waronker, along with fellow Warner Brothers record

executive Mo Ostin, was able to get Simon in contact with South African record producer

Hilton Rosenthal, who found the musicians that recorded “Gumboots” (Hilburn 2018,

252).

5

Initially when Simon got in contact with Rosenthal, he wasn’t sure what he

wanted to do with the song “Gumboots,” but simply wanted to buy the rights to the

recording and see if he could use it for his own material (Carlin 2016, 280). When he

mentioned to Rosenthal that he was considering recording his own vocal track over the

Boyoyo Boys instrumental, Rosenthal insisted that the track was not up to the technical

quality of a Paul Simon recording, and alternatively he should consider coming to South

Africa and hiring the musicians that played on the track to re-record his own version of

the song (Hilburn 2018, 252). When Simon presented the idea to Waronker by singing a

vocal line he had written over the tape, Waronker didn’t see the point of going all the way

to South Africa, telling Simon “you can just do that here in New York. Just get a couple

great players, you’ve got the instrumentation, the players can certainly do that”

(Berlinger, 2012). Simon, however, wanted his record to be as accurate to the tape as

possible, and told Waronker that he intended to make the trip to South Africa (Berlinger

2012). Simon recollects at the time that “it was an adventure that seemed irresistible to

me, and of course I was fascinated and intimidated by the fact that I’m coming to South

Africa” (Berlinger 2012). It was also at this point that Simon consulted Harry Belafonte,

a known anti-apartheid activist, who told him to make sure it was known to the African

National Congress that he was planning to make the trip despite a cultural boycott. Simon

ignored Belafonte’s suggestion and would eventually face heavy criticism for this

controversial decision (Berlinger 2012).

To aid Simon in his attempt to locate the musicians that he had heard on the

mixtape, as well as find more music he may want to use on the project, Waronker enlisted

the help of African and Jamaican music expert Robert Steffens, while Rosenthal got in

6

contact with South African producer Koloi Lebona (Hilburn 2018, 252). In early

February 1985, Simon and producer Roy Halee arrived in South Africa to begin sessions

at Ovation studio in Johannesburg (Carlin 2016, 282). Simon and Halee both were

relieved and excited to find that the studio was a state of the art, 24-track studio which

would be able to produce tracks of a much higher quality than the original instrumental

that Rosenthal deemed not up to par with Simon’s music (Hilburn 2018, 254). With the

recording space secured, all that was left to do was to bring in the musicians that Lebona

had found and begin recording material for the album.

Rosenthal recalls that the original sessions were “organized pretty quietly,” as

they began to bring in musicians to work with Simon after contacting representatives for

the groups Simon was familiar with (Berlinger 2012). Simon at first encountered some

concern from South African musician’s union members that he could potentially be

taking advantage of the musicians for his own monetary gain, however he soon earned

the support of the musicians by guaranteeing to pay the session players three times New

York union scale, as well as share any writing credits with the musicians who contributed

to the material (Carlin 2016, 283). Simon began bringing in members of South African

groups Tau Ea Matsekha, General M.D. Sharinda and the Gaza sisters, and Stimela to

have jam sessions in the studio that would be recorded for ideas for material (Berlinger,

2012). It was at this point that Bakithi Kumalo, who had been playing bass for Tau Ea

Matsekha and would become the main bassist on the album, got a call while working at a

car mechanic’s shop that Paul Simon wanted him to come down to the studio and record

(Bradman 2016, 30). Kumalo, who was mainly interested in South African music, was

7

unfamiliar with Simon’s material until Lebona sang “Mother and Child Reunion,” and

Kumalo recognized the melody (Hilburn 2018, 254).

With the musicians assembled for his project, Simon was ready to begin recording

ideas for songs. Halee recalls that “the first day, the feeling in the room was a little

strained. That’s what I sensed. Very shy” (Berlinger 2012). Along with being in a new

place working with musicians he had never met, Simon also found himself struggling

with a language barrier between himself and musicians who didn’t speak English, at

times counting on Kumalo to act as a translator between himself and accordionist Forere

Motloheloa, among others (Hilburn 2018, 255). The first week of sessions is described by

Marc Eliot (2010, 188) as “studios filled with dozens of musicians, their wives and

girlfriends carrying babies in their arms and parked on their hips while they chanted in

the background, older children playing between the feet of all the musicians and

relatives.” In Under African Skies, footage can be seen of Simon dancing and singing

with members of General M.D. Sharinda’s band while recording an early version of “I

Know What I Know,” along with several family members and friends dancing around the

recording studio (Berlinger 2012). The recording sessions themselves were essentially

extended jam sessions between Simon and the South African musicians, described by

Roy Halee as “ten or fifteen minutes, half an hour. Lo and behold, maybe a song would

come out of that” (Eliot 2010, 190). After the first week of sessions, Simon decided to

put together a smaller set of musicians to act as the main backing band for the album,

including Ray Phiri on guitar, Isaac Mtshali on drums, and Bakithi Kumalo on bass

(Carlin 2016, 285). This was both to allow for easier communication between fewer

8

people, and also to allow the South African musicians to contribute more in the writing

process. As Phiri recalls:

Paul Simon needed a tap that he could open and out pours water. I wasn’t in his

plans when he went down to South Africa . . . After a week, things weren’t

working really fine because there was a musical communications breakdown

between the guys he was working with. He was looking for a tap, not just

musicians, but people who would give him ideas. (Luftig 1997, 169)

In the second week of sessions, the day would begin with the musicians

improvising until Simon heard something that he felt could be of use in a song, such as

the main guitar riff in “You Can Call Me Al” (Hilburn 2018, 255). At that point, Simon

would work with the musicians to get it to sound closer to something he could use to

write a song around. Msthali recalls Simon telling the musicians “feel free, play

anything” only to find that Simon was “hearing things his way” (Berlinger 2012). Simon

recollects that together they “got a really great sound, but it was all over the place and

needed to be edited and trimmed down” (Berlinger 2012). On the 25th Anniversary

edition of the Graceland album, released in 2012, some snippets of audio from these

original sessions are included as bonus tracks, allowing the listener to hear familiar

musical themes in their initial loose, improvised setting (Simon 2012). Looking back on

the sessions, Kumalo states that getting direction from Simon on how to change his

playing to fit the song he was hearing was “like going back to music school,” while

Simon remembers fondly “really learning how to combine different musical ideas”

(Berlinger 2012). Being in a situation where he was creating something so different from

his previous work, Roy Halee recalls Simon having an incredible work ethic in the initial

South African sessions, and that “Simon was so caught up in the music that he would stay

9

in the studio from noon to past midnight, long after the musicians had left, to work on

bits and pieces of music from the day’s session” (Hilburn 2018, 254).

One of the tracks that best demonstrates the collaboration between Simon and the

South African musicians during the initial Graceland sessions is the album’s title track.

While jamming over the drum groove for the track, Simon noticed that Phiri was adding a

C# minor chord while in the key of E, which was uncommon for South African music.

When Simon asked why he used that chord in the progression, Phiri told him that he had

listened to his music and that it was a chord that he recalled Simon using all the time in

his material (Hilburn 2018, 258). To Simon, “what’s interesting is that Ray reaches into

his memory for some kind of approximation of what he thinks of as American country,

and Bakithi plays straight ahead to the African groove, so the two musics find a

commonality” (Berlinger 2012). This combination of styles, which was happening

throughout the original session jams, is what gave Graceland its sound, as Simon’s

contemporary in American pop music David Byrne stated: “In Graceland you can hear

the whole phenomenon of American music being rejoined with its African roots”

(Berlinger 2012).

At the end of the two weeks of sessions in Johannesburg, Simon returned to New

York with six songs in a rough demo state for him to continue to work on (Eliot 2010,

191). It was at this point when Simon began transforming the selections from the

instrumental jams into American pop songs. Halee recalls that this was quite a task when

they returned to work on the album:

10

In the very beginning of the Graceland project, I loved what we were doing. But I

was not convinced that it was going to be great. In the beginning, anyway. I loved

the music we were recording. But there were no songs written yet, so it was shaky

ground as far as I was concerned. But I loved the feel of that stuff. And then we

brought it back and edited the hell out of it. The digital editing worked very well

for us in that respect. It makes doing involved editing much easier. On that

project, without it, I would have been in serious trouble (Luftig 1997, 197).

After they had cut down the demos, Simon “went out and tried desperately to put words

to each one” (Berlinger 2012). Simon had to adapt his typical American songwriting to fit

the new style he was writing in, and was forced to “listen harder to the rhythm” in order

to come up with phrases that fit over the complex rhythms and countermelodies present

on the instrumental tracks (Hilburn 2018, 262). Simon also points out the importance of

listening to Kumalo’s bass lines when writing his vocal lines, stating “when I started to

really listen, I realized that the guitar part was playing a different symmetry than I had

assumed it was doing, and the bass was doing something much more important, and that

you really might be better off following what the bass was doing” (Berlinger 2012). The

album’s “satirically urbane” lyrics, which “jar so strangely with the indigenous south

African music,” provide another layer of crossing musical cultures on the album, further

demonstrating the unlikely collaboration between Simon and the South African musicians

(Bonca 2015, 111).

Once Simon had the songs written, he decided to bring his South African studio

band to New York to overdub and re-record parts of the album (Carlin 2016, 288). He

also began sharing early versions of his new project with other friends and musicians,

including composer Philip Glass, who thought “This is a real breakthrough, this is going

to be a masterpiece” (Hilburn 2018, 260). Around this time, Simon got in contact with

Joseph Shabalala, a member of South African vocal ensemble Ladysmith Black

11

Mambazo, and made plans to fly them to Abbey Road studios in London to record what

would become the tracks “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” and “Homeless” (Carlin

2016, 288). Simon had heard of the group from a documentary entitled Music of

Resistance, and had sent Shabalala a rough idea of what he had in mind for the track

“Homeless” (Berlinger 2012). After completion of the final two tracks to feature South

African musicians, Simon left to record two more tracks he had already planned for the

album, the first being “That Was Your Mother,” a New Orleans zydeco track recorded

with accordionist Rockin’ Dopsie in Crowley, Louisiana (Hilburn 2018, 257). The

closing track of the album, “All Around The World or the Myth of Fingertips,” was

recorded with Los Lobos in North Hollywood, though there was tension between the

group and Simon throughout the recording process and after its release (Hilburn 2018,

261). These two tracks remain at the end of the album from its initial concept of being an

“around the world with Paul Simon” type of album before the South African style

dominated the tracklist and the concept was scrapped (Carlin 2016, 292).

When the album was complete, Simon brought it to Lenny Waronker who

remembers “I was a little nervous because of all that Paul had gone through in recent

months, but as soon as I heard the music I was relieved” and called the music “a smart

dance record” (Hilburn 2018, 251). When it came time to present the album to Warner

Brothers, Halee remembers thinking “A lot of people in the room were probably

wondering why they were wasting their time with another Paul Simon album,” though the

meeting was a success and the label decided to delay the release of the album from its

planned May 1986 release to a September 1986 release instead in order to focus more on

promotion (Hilburn 2018, 271-272). The label reportedly wasn’t sure on how to market

12

the album due to its combination of world music and pop (Carlin 2016, 291).

Consequently, the album’s only charting single was “You Can Call Me Al,” reaching #23

on its first release and #11 on its second (Bonca 2015, 111). Despite the underwhelming

chart success of its singles, the album became a hit in its own right, selling over five

million copies in the US alone and over sixteen million worldwide (Hilburn 2018, 282). It

also won the Grammy for album of the year, beating out artists such as Janet Jackson,

Steve Winwood, and Barbra Streisand (Eliot 2010, 195-96).

Though the album accordingly could “take a westerner’s ears a little getting used

to,” on tracks such as “I Know What I Know,” the blend of South African and American

pop lent itself well to the album’s popularity and became a hit with both critics and fans

alike (Bonca 2015, 111). Though Simon’s career had taken major blows on previous

releases, Graceland revitalized his popularity being noted as “one of the most

phenomenal comebacks in the history of show business” allowing the songwriter to

“redefine himself and his music not merely as an entertaining presence but a cultural

force” as Marc Eliot wrote (Eliot 2010, 196). The instrumentals provided by South

African sessions musicians combined with Simon’s vocals were praised by many,

described by Bonca (2015, 103) as “a tantalizing gumbo of world music that mingled

several traditions into a rhythmically stirring, aurally lustrous, melodically tuneful, and

lyrically arresting album.” Because this new style resonated so well with fans of Simon’s

music and critics alike, his future songwriting projects would find a new direction in

incorporating more elements of world music, such as on his 1990 release The Rhythm of

the Saints, which features both African and Brazilian musicians (Simon 1990). Perhaps

13

when Simon cited Graceland as the most significant achievement of his career he was

correct, if not simply for the way it redefined his sound.

14

Chapter Two:

Bakithi Kumalo and South African Township Music

The main bassist on Graceland is Bakithi Kumalo, whose melodic fretless bass

playing lends itself to many of the album’s iconic moments. Kumalo was born in the

Alexandra township in South Africa in 1956 and grew up in a musical household. He was

raised by his mother, who was a singer and guitarist, and often spent time with his uncle,

who played in a swing band (Jisi 2008, 28). By the age of seven, Kumalo had left school

without learning to read or write, but had already demonstrated a talent for music.

Kumalo got his start on bass one night during a set of his uncle’s swing band, when the

regular bassist showed up too drunk to play the gig and the young musician stepped in.

By the age of 10, he had started his career as a professional musician, now a regular

member of the group (Delatiner 2004, LI12).

Throughout the 1970s, Kumalo worked his way up to becoming a well sought-

after session player throughout all of South Africa, and by the early 1980s he was one of

the most well-known electric bass players in the area (Jisi 2008, 28). One of the first

groups Kumalo played in was a cover band called the VIPs who played mostly American

R&B tunes, though at times would mix in township music, or alter the sound of the R&B

songs to more closely resemble township music. While Kumalo was on tour with the

VIPs, the band found themselves stranded for sixteen months unable to return home,

surviving mainly on sugar cane and oranges. Kumalo eventually returned home to his

15

mother, without a bass, and was forced to practice on a makeshift cardboard drawing of a

fretboard. This, however, inadvertently aided Kumalo in finding the unique sound that

would come to make him famous on Graceland, as the replacement bass his mother

bought for him was the fretless Washburn B-20 that provided the recognizable growl in

Kumalo’s sound on the record. Kumalo would continue to make his rounds as a popular

session player, joining American acts who played in South Africa such as the Brothers

Johnson and Harry Belafonte. But it was the township group Tau Ea Matsekha that

caught the ear of Paul Simon, who loved Kumalo’s bass lines so much that he needed to

bring him in to play on Graceland (Bradman 2016, 29).

While the swing music his uncle played gave Kumalo his start and had a strong

influence on his musical development, he was also influenced by traditional South

African music and American pop. Kumalo cites American electric bass masters such as

Stanley Clarke, Victor Bailey, Marcus Miller, and of course fretless pioneer Jaco

Pastorius as main inspirations on his playing (Jisi 2008, 29). In terms of South African

influence, Kumalo drew inspiration from music he had heard all around him growing up.

He cites learning bass voice parts from traditional South African vocal music as a key

factor in the development of his unique voice on the instrument (Jisi 2009, 79).

According to Kumalo, when writing a bass line he likes to “hold down the groove, and

then I find my space to sing” (Jisi 2008, 29). This approach can be heard in several spots

on Graceland where Kumalo alternates from staying in a supporting role to playing a

more melodic line, reminiscent of the types of vocal melodies he would have heard.

Another inspiration was accordion-based township music, which featured accordion bass

16

lines that Kumalo would listen to and try to replicate on his own instrument (Jisi 1998

29).

The main type of township music Kumalo was drawing inspiration from and

playing by the time Simon came along was known as mbaqanga (mɓaˈǃáːŋa), a genre that

gets its name from a Zulu word for a type of corn bread, a play on jazz musicians earning

their “daily bread” through the music’s performance (Coplan 2008, 420). Mbaqanga as a

style of music can be traced back to an earlier style of South African music called

marabi, which gained popularity as early as the 1930s and was influenced by early

American jazz (Graham 1988, 258). The influence of Western music on the music of

South Africa was not uncommon by the time marabi became popular. Well before the

turn of the 20

th

century, Western instruments such as guitars, saxophones, and accordions

were introduced to South African musicians, and would become the backbone of South

African township music (Graham 1988, 257). With the introduction of recorded music to

South Africa, American jazz became a popular genre among the consumers who owned

turntables (Graham 1988, 258). Because of the external influence of American music and

Western instruments, South Africa became a “unique melting pot for European and

indigenous musical influences,” which resulted in the sounds of marabi, and later on

kwela and mbaqanga having distinct African qualities, while otherwise resembling

American jazz (Graham 1988, 257). Musicians, such as Kumalo’s uncle’s band, learned

to play the music they heard on records while also incorporating elements of their own

traditional music, and incorporated traditional compositions into performances, to create

a unique blend that would become the basis for the genres that would come later (Bender

1991, 175).

17

One of the main factors that lent itself to the development of township music were

the townships themselves. As a consequence of Apartheid, many black South Africans

were relocated to townships described as “huge workers’ settlements, like camps” in

order to work for the benefit of white South Africans (Bender 1991, 173). Because of the

number of people from different backgrounds relocating to these areas, different musical

traditions began to be blended, which inadvertently helped in the development of marabi

(Bender 1991, 173). As a form of entertainment after a day’s work, musical performances

were held in shebeens, which were private houses where alcohol was illegally sold and

workers would gather to drink and listen to music (Bender 1991, 175). As was the case

with the other forms of township music that followed, marabi developed and survived

through live performance (Impey 2008, 139).

The live nature of township music led to the creation of a new genre called kwela

(kweɪlə), which gets its name from “kwela-kwela,” a phrase inviting audience members

to get up and dance (Bender 1991, 180). By the mid-1950s, the genre became the

dominant sound in South Africa over marabi, as the so-called “kwela boom” began

(Floyd 1999, 227). As township music evolved, its audience began to favor music that

leaned more towards its South African roots and less towards American swing (Floyd

1999, 227). Kwela music revolved around short and memorable repetitive melodies

played on pennywhistle or saxophone, accompanied mainly by acoustic guitar, though

full rhythm sections were common later in the genre’s lifespan (Floyd 1999, 229). One of

the main distinguishers between kwela and mbaqanga or marabi was the style’s heavy

emphasis on the shuffle feel of its compositions (Floyd 1999, 229). The main factor that

caused the addition of the rhythm section, consisting of drums and bass, was the “fullness

18

of sound” needed to create quality recordings at the time (Floyd 1999, 231). Some

makeshift instruments that would be utilized in live settings, such as tea kettle basses,

were swapped for their Western counterparts on recordings, which ultimately led to

changes in how the music was composed to make it more applicable to Western

instrumental techniques (Bender 1991, 179).

An example of this style of playing can be heard on Spokes Mashiyane’s 1958

track “Jika Spokes,” which showcases the type of pennywhistle-driven music that had

gained popularity (Mashiyane 1991). Mashiyane was one of the genre’s most popular

artists, and his recordings were credited with causing the “kwela-boom” (Floyd 1999,

228). The influence from American music can be heard on this track, as the rhythm

section resembles the instrumentation that can often be heard in American blues, a style

whose 12-bar form had an influence on the genre as well (Floyd 1999, 228). Saxophones

were also introduced as an alternative lead instrument in kwela, which can be heard on

another Mashiyane track titled “Banana Ba Rustenburg,” included on the compilation

album African Jazz ‘n Jive (Mashiyane 2000).

Along with the shift to saxophone as the main melodic instrument, a further

development in township music was made with the introduction of the electric guitar,

resulting in the creation of mbaqanga (Floyd 1999, 236). According to guitarist Zami

Duze, a main difference between playing kwela and mbaqanga was that mbaqanga was

faster, requiring guitarists to be more technically proficient (Floyd 1999, 236). Coplan

(2008, 420) writes in The Garland Handbook of African Music that the genre was born

out of the late hours of live music performances, where musicians would improvise by

incorporating more elements of their traditional music into the more Western sounding

19

township music of the time. The word “jive” was added to the style as a descriptor to the

style as other changes took place, including the introduction of electric bass as an

essential member of the rhythm section (Coplan 2008, 423). Where kwela had related

more closely with marabi and American music, mbaqanga found more in common with

traditional African instrumental music, now featuring an emphasis on syncopation,

typical AABB form, and fast tempos in a straight 2/4 feel (Coplan 2008, 424).

One of the most popular artists who recorded in the mbaqanga style were the

Mahotella Queens, led by frontman (also known as a “groaner”) Simon “Mahlathini”

Nkabinde (Impey 2008, 139). The typical early mbaqanga sound, which even early on

resembled the Graceland sound, can be heard on the 2019 reissue of the group’s popular

album Meet the Mahotella Queens. The album’s opening track. “Kuqale Bani,” features a

call-and-response vocal, and counter-melodies in the guitar and electric bass played over

a light upbeat drum pattern in a simple three chord progression (Mahotella Queens

2019b). Some of the early mbaqanga tracks, such as “Ikhula” from the same release,

feature basslines played on upright bass which are more in line with kwela lines, given

that they are simpler and acting mainly as a support instrument, though instead of

walking bass lines they typically play a repetitive rhythmic vamp over the simple chord

progression (Mahotella Queens 2019a).

The main bassist for the Mahotella Queens was Joseph Makwela, who Kumalo

cites as the main influence on his playing (Bradman 2016, 29). Along with playing for

the Mahotella Queens, Makwela was also the bassist for a later mbaqanga group called

Makgona Tsohle band, which played in the saxophone jive style of mbaqanga (Harris,

n.d.). Makwela’s style of playing is uniquely rooted in African music, as it is believed

20

that he was the first black man in South Africa to own an electric bass, and thus was the

main pioneer of the instrument’s role in mbaqanga (Bishop 2010, 61). Makwela’s bass

lines are typically heavily syncopated, played high up on the neck of the instrument in its

upper register, and equally as melodic as the lead guitar figures in the songs. Because of

his distinct style of playing, many similarities can be heard in Makwela’s bass lines and

Kumalo’s playing on Graceland. For example, Makwela’s line on the track “Kotopo” is

similar both rhythmically and melodically to Kumalo’s line on “You Can Call Me Al,” in

a song that is written around the same chord progression (Makgona Tsohle Band 2007a).

Part of Kumalo’s bass melody in the verses of “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” is

nearly identical to the intricate, descending melody that Makwela plays on “Red Light,” a

track where the bass is featured even more prominently than on the Simon track

(Makgona Tsohle Band 2007b). These tracks not only serve as examples of typical South

African electric bass playing, they also represent the type of music that the artists Simon

hired for Graceland would have been drawing upon for their instrumental tracks.

It is clear simply from the way Kumalo approaches his bass lines that a large part

of his sound on Graceland is due to the influence of Makwela and other mbaqanga artists

in general, is a large part of his unique sound on Graceland. Because Simon kept the

South African influences as authentic as he did in the studio, the bass lines on Graceland

can be seen as directly drawn from the mbaqanga tradition. Many elements of Makwela’s

distinct style that became associated with mbaqanga, such as sliding, upper register

playing, and syncopated melodic lines can be heard throughout Graceland’s bass lines.

Thus, the bass lines can be analyzed as mbaqanga bass lines within the South African

musical tradition, despite the music itself being influenced by Western sounds. Because

21

of the bass’s role in these forms of music, and how basses developed from a supporting

role in marabi and kwela, it can also be said that Kumalo’s bass lines provide a key part

of the album’s sound, as they act as a key melodic element within mbaqanga.

22

Chapter Three:

Elements of South African Music Within the Bass Lines of Graceland

The bass lines on Graceland feature a variety of elements that draw from both

traditional South African music, as well as more modern styles of township music, such

as mbaqanga and kwela. As is stated in the Da Capo Guide to African Music, the role of

music within the culture and daily lives of African people makes it “almost impossible to

conceive of a division between ‘classical’ and ‘popular’ music in Africa as obtains in the

west,” and such distinction would be irrelevant due to the ways in which traditional

music “remains the musical mainstay for the vast majority of Africans” (Graham 1988,

9). Thus, when analyzing the instrumental tracks, specific elements of both traditional

and neo-traditional South African music (as these styles are referred to in The Garland

Handbook of African Music) can be found within the Graceland tracks. The goal for

these analyses is to identify key ways in which these elements are present within the bass

lines in order to then determine how they affect Simon’s songs on Graceland and

beyond.

While the original instrumental session tracks were ultimately rearranged, cut up,

and overdubbed to better fit Simon’s writing style, the instrumental backing tracks that

remain still draw heavily from South African musical tradition. Coincidentally, the

somewhat “cut-and-paste” nature of the arrangements ultimately works in favor of the

23

analyses, due to the cyclical and repetitive nature that is an important element of all

traditional African music (Floyd 1999, 8). However, Christopher James states in

Composing African Music that simply being repetitive and cyclical isn’t what makes the

music interesting, stating “what is important is how the African musician achieves variety

and maintains interest within a cyclical framework, not the mere fact that the music is

repetitive” (Floyd 1999, 8). Within these cyclical patterns, interesting instrumental lines

are created by complex, interlocking passages, creating the rhythmic complexity that is

the “hallmark of African music” (Floyd 1999, 12). This type of cyclicity and repetition is

equally present within kwela and mbaqanga. Lara Allen writes: “structurally, kwela

music consists of the repetition of a short harmonic cycle over which a series of short

melodies or motifs, usually the length of the cycle, are repeated and varied” (Floyd 1999,

228). This element of repetition and cyclicity remained as mbaqanga became the

dominant genre, and became increasingly prominent in the music as it began to embrace

more of its South African roots. Thus, because of the ways in which repetitive fragments

of rhythmically complex instrumental material are used to create the backing tracks for

Simon’s Graceland songs, it becomes possible to easily identify the repetitive cycles and

identify variation within them. This is helpful when analyzing the bass lines, as it is easy

to see how the bass lines interact with other instruments to create rhythmically complex

backing tracks.

Along with electric bass, the rhythm section on the tracks Simon recorded with

South African musicians consisted mainly of one or two guitars and drum kit. On some

tracks, accordion and synthesizer are added in as well, and many tracks include at least

one form of auxiliary percussion, though it does not sit as prominently in the mix as the

24

main instruments. This ensemble is fairly typical of South African township music, and

the roles of the instruments align with similar roles within traditional and neo-traditional

South African music. Texturally, these instrumental arrangements on Graceland are

nearly identical to more authentic mbaqanga ensembles, and the roles of individual

instruments, including the electric bass, remain essentially the same.

When looking at traditional African instrumental music, many instruments have

clearly defined purposes within the ensemble. As is stated in The Music of Africa:

instruments are selected in relation to their effectiveness in performing certain

established musical roles or for fulfilling specific musical purposes. While some

instruments are designed for use as solo instruments, others are intended for use in

ensembles. Within such groups, certain instruments function as lead or principal

instruments, while others play a subordinate role as accompanying or ostinato

instruments. Some instruments are used for enriching the texture of a piece of

music or for increasing its density, while others emphasize its rhythmic aspects or

articulate its pulse structure (Nketia 1974, 111).

The same can be said for the mbaqanga styles from which Simon’s backing band draws

their instrumental lines. In many cases of mbaqanga, the drums will provide a simple

repetitive beat while the guitars and electric bass switch off playing melodic passages or

repetitive ostinato figures. In examples of mbaqanga and kwela where a lead instrument

such as a saxophone is present, the guitars and basses may play more background-

focused lines while the lead instrument takes the melody. In the case of Graceland,

electric guitars typically play repetitive interlocking rhythmic figures, while the electric

bass switches between repetitive supporting patterns and melodic passages that either act

as a countermelody with the lead vocal, or take over as the main melodic passage for the

section. As is noted in Composing African Music, a main feature of this music is both the

25

guitar and bass having an “independent melodic line resulting in the contrapuntal texture

of mbaqanga” (Floyd 1999, 257).

Because of the importance of these interlocking rhythms within the guitar and

bass parts on Graceland, one of the main elements that will be noted within the analyses

in this chapter will be significant examples of interlocking rhythms that clearly draw

from South African musical tradition. Floyd states in Composing African Music that

“African traditions are more uniform in their choice and use of rhythms and rhythmic

structures than they are in their selection and use of pitch systems. Since African music is

predisposed towards percussion and percussive textures, there is an understandable

emphasis on rhythm, for the lack of melodic sophistication” (Floyd 1999, 125). Though

the majority of the South African music on Graceland is relatively simple in terms of

harmony, its rhythmic complexity is in line with this description traditional South African

music.

A key aspect of traditional African rhythm, which extends into mbaqanga, is the

use of cross rhythms and polyrhythms. As is written in Composing African Music:

The African approach to rhythm is that at least two separate and independent

rhythms should occur simultaneously, thereby producing in combination rhythmic

complexities not found in most Western music. In Western music rhythmic

patterns reinforce and emphasise the essential metric pattern, whereas in African

music separate rhythmic patterns conflict with one another to produce

polyrhythmic combinations and multi-metric patterns (Floyd 1999, 12).

In The Music of Africa, J.H. Kwabena Nketia describes the two main forms of rhythm in

traditional African music as “additive” and “divisive.” Divisive rhythms are those which

“articulate the regular divisions of the time span” and “follow the scheme of pulse

26

structure in the grouping of notes” (Nketia 1974, 129). These rhythms may be simple

divisions of duple or triple meters, as well as hemiolas. Additive rhythms are those whose

note groupings “may extend beyond the regular divisions within the time span. Instead of

note groups or sections of the same length, different groups are combined within the time

span” (Nketia 1974, 129). The author continues, “The use of additive rhythms in duple,

triple, and hemiola patterns is the hallmark of rhythmic organization in African music,

which finds its highest expression in percussion music” (Nketia 1974, 131). These cross

rhythms may be as simple as a two over three feel, or more complex with multiple

rhythms entering at different points of the phrase, and the resultant that it creates is a

single rhythmically complex sound stemming from all parts of the ensemble entering at

their respective times (Nketia 1974, 135).Within the instrumental tracks of Graceland,

much of what the bass is doing can be considered divisive rhythms, as they mainly

subdivide within the main pulse of the track, but add interesting syncopation to create

interesting lines.

The ways in which these types of rhythms are organized and spaced is part of

what helps create the strong rhythmic feel of African music. In traditional African

instrumental music, instruments are grouped based on the complexity or density within

the lines, and instruments with similar degrees of complexity will perform similar roles

(Nketia 1974, 133). This type of grouping, though not as varied, is also found in

mbaqanga, as the roles of the guitar and electric bass share a similar degree of

complexity. This results in bass lines on Graceland that are much more rhythmically

complex than Simon’s previous work. Different forms of interlocking rhythms find

themselves present throughout mbaqanga music, as guitarist Zami Duze states, “a

27

mbaqanga lead guitarist plays an independent melody line throughout containing ‘fast

singing lines’ and ‘special kind of fill-ins.’” (Floyd 1999, 236). Because of the roles of

the instruments in a typical mbaqanga ensemble, the bass lines within the style, and by

extension on Graceland, are based much more on creating interesting rhythmic lines than

on supporting the overall pulse of the song like a typical American pop bass line would.

This key feature of the style is one of the main elements that makes the role of the bass

on this album stand out when compared to Simon’s earlier material.

In terms of harmony, most kwela and mbaqanga compositions follow a simple

repetitive progression mainly featuring I, IV, and V chords in a major key (Floyd 1999,

229). Much of Graceland follows typical mbaqanga fashion by sticking to relatively

simple three chord progressions, and because of this the bass lines are equally simple in

terms of harmony. Much of what the bass is doing is simply outlining the major chords

within the progressions, though on some tracks there is emphasis placed on non-root

notes. Most scales featured in traditional African melodies are based on four to seven

steps, with some resembling Western modes (Nketia 1974, 117-118). Because mbaqanga

has a notable influence from Western music, the majority of the melodic lines within the

bass lines on Graceland fall within Western major and pentatonic scales.

Some of the more melodic passages within the bass playing on Graceland also

have elements of South African vocal music, which is not surprising as Kumalo had cited

vocal music as an influence in his early playing style. Like traditional African music and

mbaqanga, South African vocal music relies on interlocking moving parts, many of

which occur in a call-and-response fashion (Nketia 1974, 144). The main difference

between the two types of music, however, is stronger harmonic and melodic focus due to

28

the nature of vocal music. This is achieved partly through the use of parallel intervals,

typically thirds and fourths depending on which scale is being used, as well as fifths,

unisons, and octaves (Nketia 1974, 161-62). This is combined with the contrapuntal

nature of South African vocal music to create a texturally rich sound that can be heard on

the two Graceland tracks that feature Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Because of the

melodic nature of Kumalo’s fretless bass playing, some of the bass lines on Graceland

interact with Simon’s lead vocal in a similar contrapuntal fashion as if they were another

voice, and can be analyzed in relation to South African vocal music. Conlan (2008, 423)

also notes in his chapter “Popular Music in South Africa” that the melodic role of the

electric bass within much of the mbaqanga style can be seen as a direct parallel to South

African vocal music, as when it is combined with background vocalists and other melodic

instrumentation it has a similar effect as the lower lead voice that is common within the

vocal tradition.

Within the bass lines on Graceland, many different techniques are used to create

interesting timbres and rhythmic effects. Many of these techniques are used to increase

the percussive element of the instrument, which is in line with the preference of

percussive passages within traditional African instrumental music, previously mentioned

from Composing African Music. One of the main techniques Kumalo uses to add a

percussive effect to his playing is the use of string muting, resulting in “dead” notes,

often preceding or placed in between fully-sounded notes and with a shorter rhythmic

duration. This, combined with a staccato attack, fills out his lines with more subdivided

rhythms that interact with other instrumental lines. This type of muting is also used

frequently by fretless bass pioneer Jaco Pastorius, whose playing Kumalo has cited as an

29

influence on his own (Jisi 2009, 37). Kumalo also uses slap bass technique, which

increases the attack of the note immensely. When combining slap technique with string

muting, the result is a heavily articulated percussive sound with no sounding pitch, acting

almost as an auxiliary percussion instrument. Another effect that is utilized in many

mbaqanga songs, and is amplified by Kumalo’s use of fretless bass, is the use of sliding

between notes, which shows up in nearly every track on Graceland. Through combining

all of these techniques, Kumalo is able to create a distinct bass sound that is unique

among Simon’s discography, as well as American pop music in general.

The remainder of this chapter will consist of a track-by-track analysis of the

basslines on Graceland within the songs that feature South African musicians, excluding

the acapella track “Homeless.” The opening track of the album, “The Boy in the Bubble,”

features a steady shuffle feel eighth note groove in the verses, shown in Example 3.1.

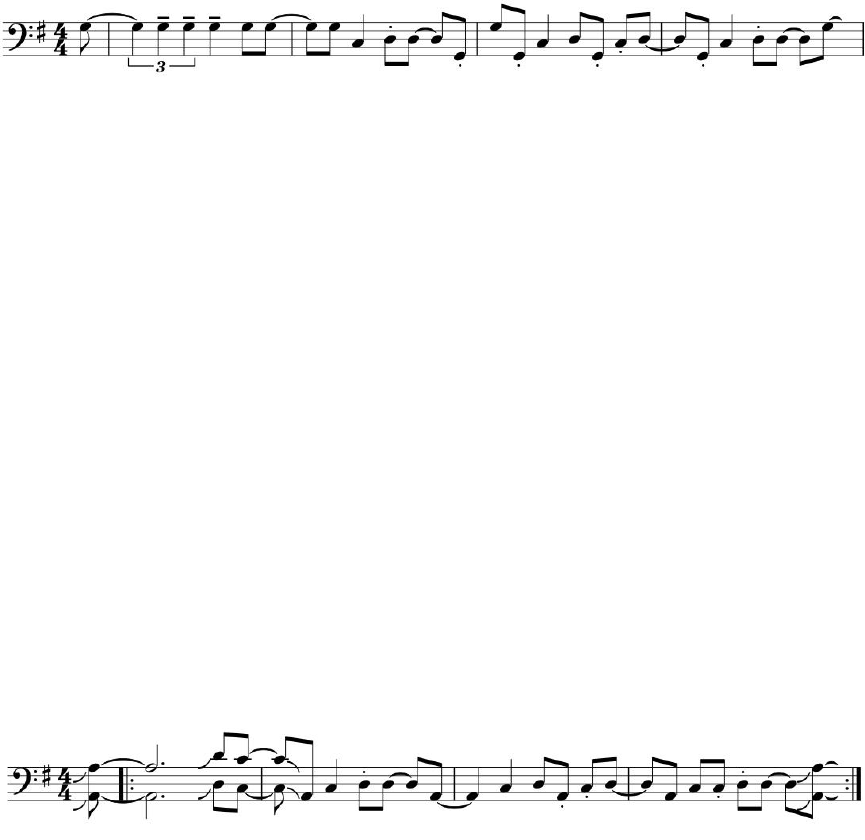

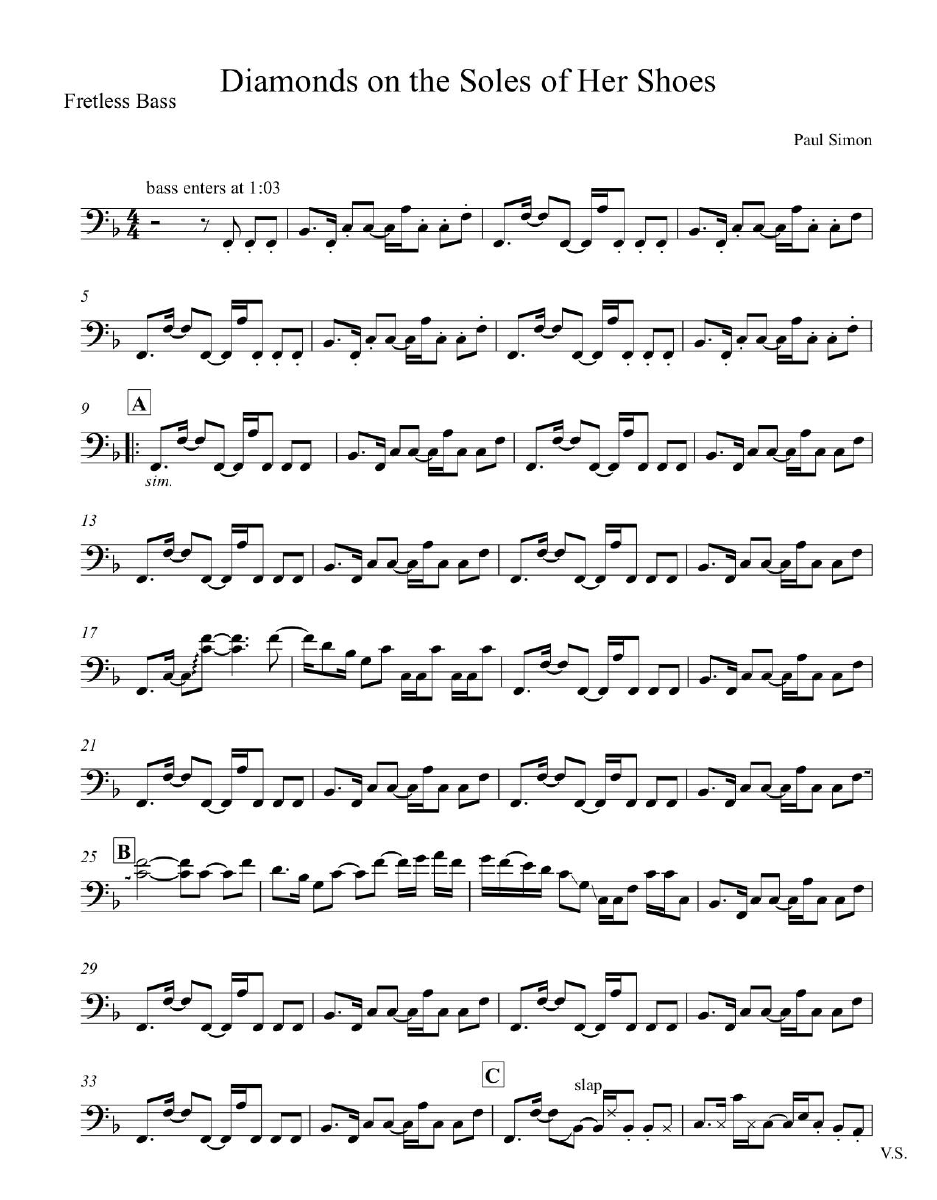

Example 3.1 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 9-12

This type of bass line, while not commonly found in mbaqanga, comes from the typical

kwela groove, described by Lara Allen as a “lilting shuffle,” derived from the swing feel

of early jazz (Floyd 1999, 229). While typical kwela bass lines are similar to American

walking bass lines, it is not uncommon to feature eighth note upbeats similar to what

Kumalo is playing on this track (Floyd 1999, 233-34). This bass line, along with the

shuffle-feel drums, contrast with the straight eighth feel of the accordion, being played in

a style of accordion-based township music called famo (Carlin 2016, 286). The

30

juxtaposition of these two rhythmic feels creates an interesting combination within the

song. The chorus, shown in Example 3.2, features a shift from the steady shuffle feel in

the bass to a quarter note triplet pulse for the first half of the measure followed by a

similar shuffle eighth note feel, adding another rhythmic variation to the mix.

Example 3.2 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 25-28

Both the verse and chorus begin with a tied eighth note pickup. It is not uncommon

within South African music for instrumental lines to avoid placing the beginning of a line

on beat one, which is seen in many of Graceland’s bass lines (Floyd 1999, 12). There is

also a change in tonality, as the song shifts from an A minor key center to G major. This

type of tonality shift is common among some South African vocal music, as is noted in

The Garland Handbook of African Music (Kaemmer 2008, 389).

Following the chorus is a section where the bass acts as the main melodic

instrument, pictured in Example 3.3.

Example 3.3 “The Boy in the Bubble” measures 41-44

31

This figure features parallel octaves played by the bass as well as sliding. This bass

melody may be seen as an example of the influence of South African vocal music within

the bass melodies, as the line has a somewhat choral quality to it with Kumalo’s sliding

vibrato, and parallel open intervals. Kumalo himself has stated that the ability to slide on

a fretless bass allowed him to achieve vocal-like qualities within his playing, further

acting as an example of the influence of vocal music on his playing (Jisi 2009, 37).

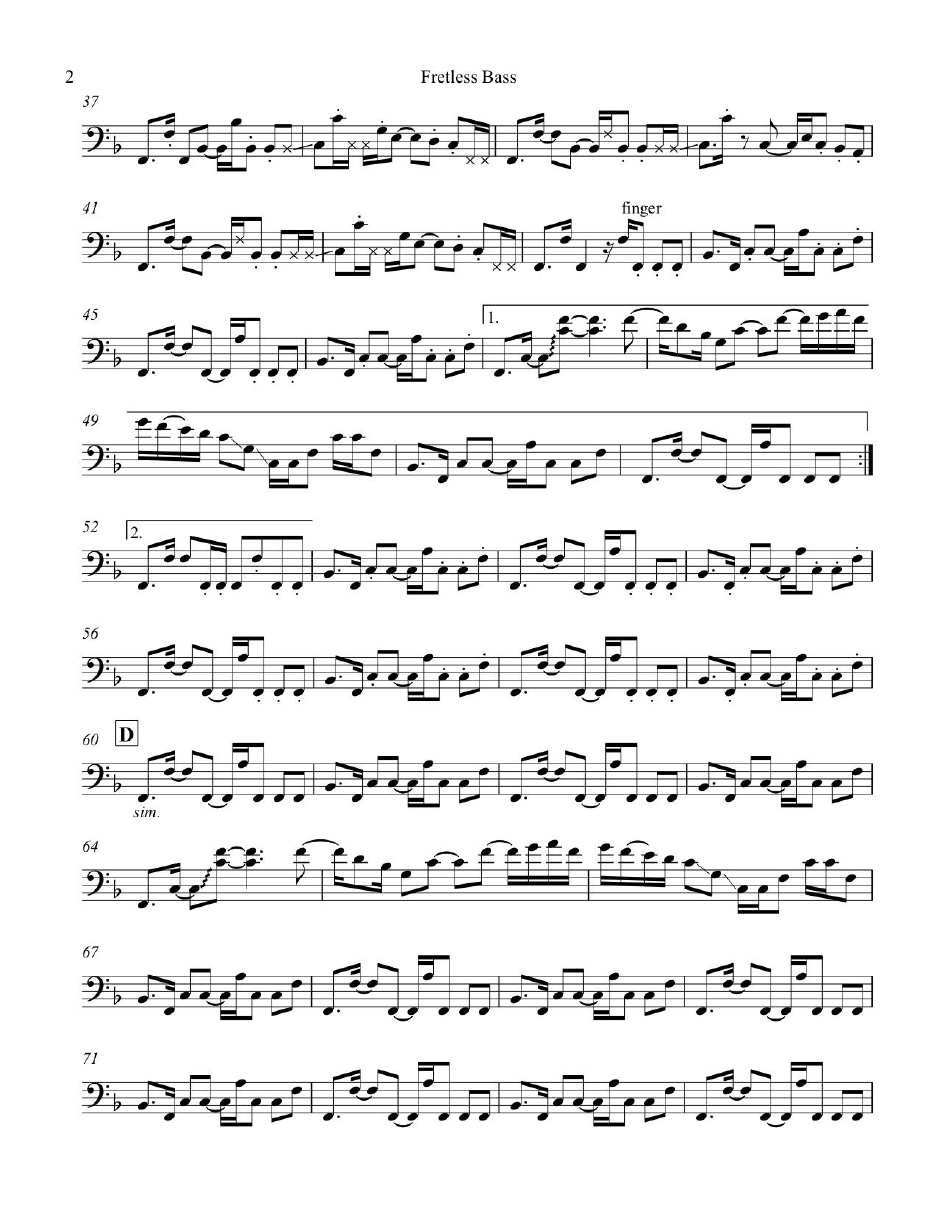

As I mentioned in Chapter One, the second track of the record, “Graceland,” is

one of the albums best examples of a combination of American and South African styles

of music. The track starts with long root notes played by the fretless bass over eight bars

that enter on an eighth note pickup. The rhythm guitar strums steady sixteenth note

chords in a I-IV-vi-V progression, while the drums play what Simon refers to as a

“traveling rhythm,” reminiscent of 1950s American country (Simon 2012d). The lead

guitar enters with a smooth, syncopated melody backed with a reverb-soaked slide guitar

playing the same line, which would not sound out of place on an American country song.

The bass line, however, is what brings an element of South African music into the verses

of this track. Pictured in Example 3.4, the bass line starts with a muted sixteenth-note

pickup and moves into a steady eighth-note octave groove.

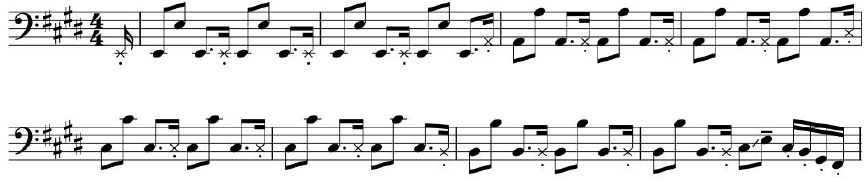

Example 3.4 “Graceland” measures 9-16

32

Were Kumalo to play a line in a more traditional country style, he would perhaps stick to

quarter notes on the downbeats with the kick drum, switching back and forth between the

root and fifth of the chord. His choice to play a syncopated eighth-note subdivision is

more in line with African music. In this instance, the kick drum has the largest division of

the measure with quarter notes, acting in a similar role to the “time-line” in traditional

African music that keeps time for the ensemble (Nketia 1974, 132). Where playing

quarters would be somewhat redundant, the eighth note bass line splits the difference

rhythmically between what the guitar and drums are playing, while the muted sixteenth-

note pickup adds an extra percussive element to the line. The bass ends the eight-bar

chord progression with a sixteenth note pentatonic run, (a scale found in both American

folk and South African music), leading back to the I chord.

The chorus, shown in Example 3.5, features the bass and guitar acting as parallel

voices along with Simon’s vocal line. The line ends with the guitar and bass taking over

the melody with an eighth note triplet figure in a call-and-response fashion before

repeating Simon’s initial melody while he switches to another for the second half of the

chorus. While it is likely Simon simply changed the melody to fit his lyrics, call-and-

response playing as well as vocal improvisation can be seen as elements from South

African music. The triplet figure is also an example of a three-against-two rhythm that

would be common in South African instrumental music, and rarely found in American

country.

33

Example 3.5”Graceland” measures 28-32

Track three, “I Know What I Know,” is an excellent example of how the electric

bass is typically utilized in neo-traditional South African music. The track features some

of the record’s most percussive and rhythmically complex playing among all instruments,

as well as female backing vocals performed by The Gaza Sisters that sit quite

prominently in the mix. There are two main variations of the bass line, the first of which

is pictured in Example 3.6, following the electric bass’s entrance at the beginning of the

track which features more fretless bass sliding. Example 3.7 shows a variation of that line

featuring playing in a lower register, and the use of fifths as opposed to octaves, both

which are common in South African bass playing.

Example 3.6 “I Know What I Know” measures 3-5

Example 3.7 “I Know What I Know” measures 8-9

34

This use of octaves and fifths allows for a natural accent on upbeats with the

higher notes, while playing downbeats on the lower pitches. The result is a bass line that

both keeps a steady pulse and emphasizes a syncopated rhythm, creating two contrasting

rhythmic parts within itself. The line includes sixteenth notes on the upbeat of beat three

that add a hard percussive element over the simple four-on-the-floor kick drum and hi hat

drum pattern. With the two guitars playing complex rhythmic passages that include

several three-over-two lines, the bass’s main role on this track is to provide a steady

rhythm for the track. The heavily syncopated guitar lines, along with the bass line which

both provides a steady pulse and accents upbeats, create the album’s most rhythmically

complex and distinctly South African-sounding track.

“Gumboots” is another example of a more traditional South African township

composition, due to the instrumental track being a re-recorded version of the original

Boyoyo Boys track. The bass line, shown in Example 3.8, consists of a slide from the

fifth of the chord to the root in a simple I-IV-V progression with occasional syncopated

pickup on the fifth of the chord over beat three. There is also a variation of the bass line

played in the lower octave, with a syncopated pickup figure shown in Example 3.9. In

both cases, these lines follow the trend of beginning the bass line with a syncopated

pickup.

Example 3.8 “Gumboots” measures 3-7

35

Example 3.9 “Gumboots” measures 13-17

The slides on this track are another example of the type of sliding played by Kumalo on

other tracks on the record, though not to the same extent that some of his lines take the

effect. Though the bass on this track sits mainly as a supporting instrument in comparison

to others on the record where it has a melodic role, it is still a solid example of how even

the simpler bass lines within South African music work to create an interesting rhythmic

interplay with the other instruments.

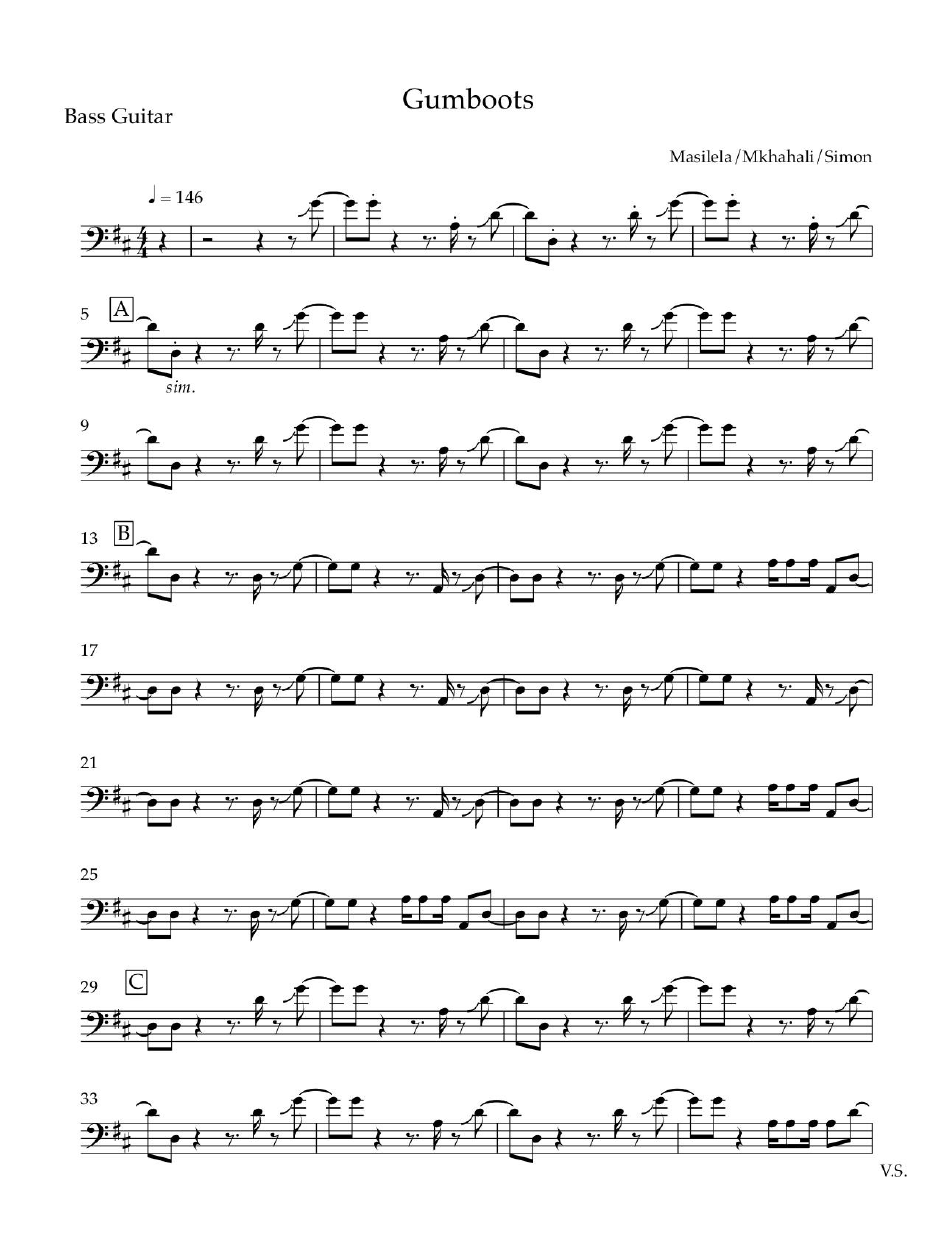

“Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” includes many fretless bass passages that

exemplify the type of melodic playing for which Kumalo is known on this album. It also

includes all three of the distinct techniques that give the bass lines on this album their

unique sound, including slapping, palm muting, and fretless slides. Kumalo’s line, shown

in Example 3.10, enters with a three eighth-note pickup that continues throughout the

verses. The line begins with a three eighth-note pickup followed by a syncopated line

featuring mainly open fifths and octaves, before repeating the pickup. Kumalo’s use of

the syncopated sixteenth-note A before the final three eighth notes of the bar creates a

natural accent on that beat that is present throughout the bass line, and adds yet another

syncopated rhythmic effect to the line.

36

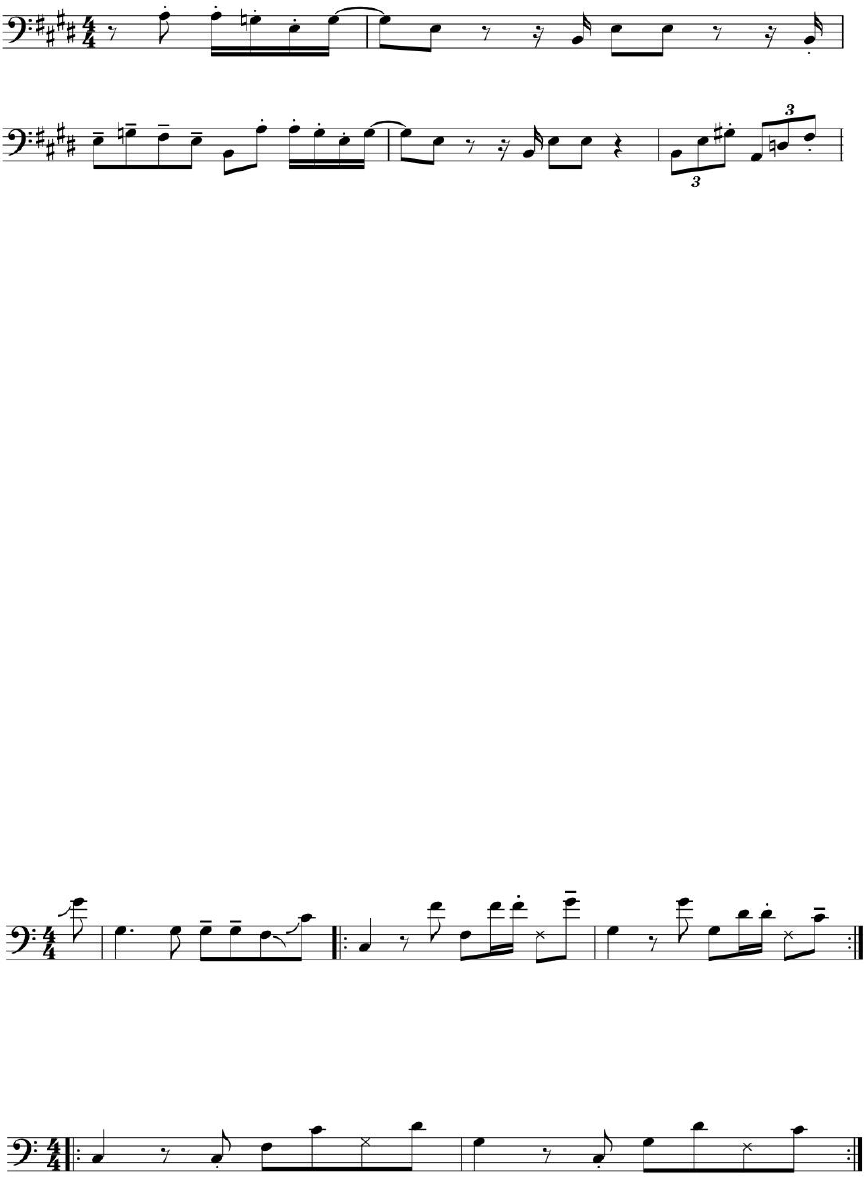

Example 3.10 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 1-3

There are two passages within the verse that have elements similar to a South African

vocal line, both occurring in the B section of the verse. Each features a double stop

parallel fourth slide up to the root and fifth of the I chord, which stands out due to the

growly timbre of Kumalo’s fretless bass. Each is then followed by a syncopated

descending arpeggio on the IV. The first passage, pictured in Example 3.11, then returns

to a syncopated octave groove to finish out the phrase before returning to the standard

verse bass line.

Example 3.11 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 17-18

In the second of the two melodic passages, shown in Example 3.12, Kumalo extends the

phrase by climbing up to the third of the chord before playing a quick, syncopated

descending line which ends by sliding down to the lower range of the instrument before

returning to the regular bass line. In both instances, this bass line takes over as the

melody of the song, with Simon singing a softer falsetto line in the background. This type

of descending melody is common within South African vocal music, as well as a more

37

complex melody sitting in the lower register with a countermelody over the top (Floyd

1999, 10).

Example 3.12 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 25-27

Finally, in the chorus, Shown in Example 3.13, Kumalo plays a more complex variation

of the verse bass line with a slap technique, while incorporating many muted notes and

slides to add additional percussive effects to the texture of the piece.

Example 3.13 “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” measures 35-43

Track six, “You Can Call Me Al,” features one of the record’s most recognizable

bass lines due to the song’s popularity, as well as a bass solo near the song’s end. Like

“Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” this track includes examples of Kumalo utilizing

different techniques within his playing. The line consists of a simple ostinato bass line

38

over a typical three-chord mbaqanga chord progression that repeats throughout the entire

track, shown below in Example 3.14.

Example 3.14 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 3-4

In the pre-chorus section of the track, a sliding fretless bass melody is added over the top

of the repeating line, shown in Example 3.15. This is another example of the fretless bass

mimicking a vocal melody. In the case of this particular melody, the bass plays along

actual voices singing the same line, while also acting as a countermelody to Simon’s lead

vocal.

Example 3.15 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 17-20

Kumalo alternates between fingerstyle and slap playing throughout the track, utilizing

slapping during the verses for a percussive effect, which towards the end of the song is

augmented with a call-and-response from hand drums. The slapped bass solo near the end

of the track (Example 3.16) is actually physically impossible to play in its recorded state,

due to the second half of the solo being identical to the first, except in reverse. Despite its

impossibility to replicate, it does serve as an example of Kumalo’s technical skill in slap

39

bass playing. Though most of the track is fairly in line with mbaqanga, the memorable

guitar and horn riff that repeats throughout the chorus is catchy enough to not feel out of

place on an American pop song. There is also a nod to kwela, with a pennywhistle solo

that happens in the middle of the track.

Example 3.16 “You Can Call Me Al” measures 122-123

The bass line of “Under African Skies” continues the trend of using slap bass and

string muting to achieve a percussive effect, while also combining slapping with fretless

sliding. The track is in a cut time shuffle feel with a simple I-IV-V progression that

repeats throughout the duration of the song. While the guitar and bass tracks are

undoubtedly mbaqanga influenced, the overall style of the song is somewhat more in line

with Simon’s earlier work, featuring an acoustic guitar-driven shuffle rhythm not unlike

the one heard on the Simon and Garfunkel track “The Only Living Boy in New York,”

though with a half-time pulse from the drums and bass. Kumalo’s bass line during the

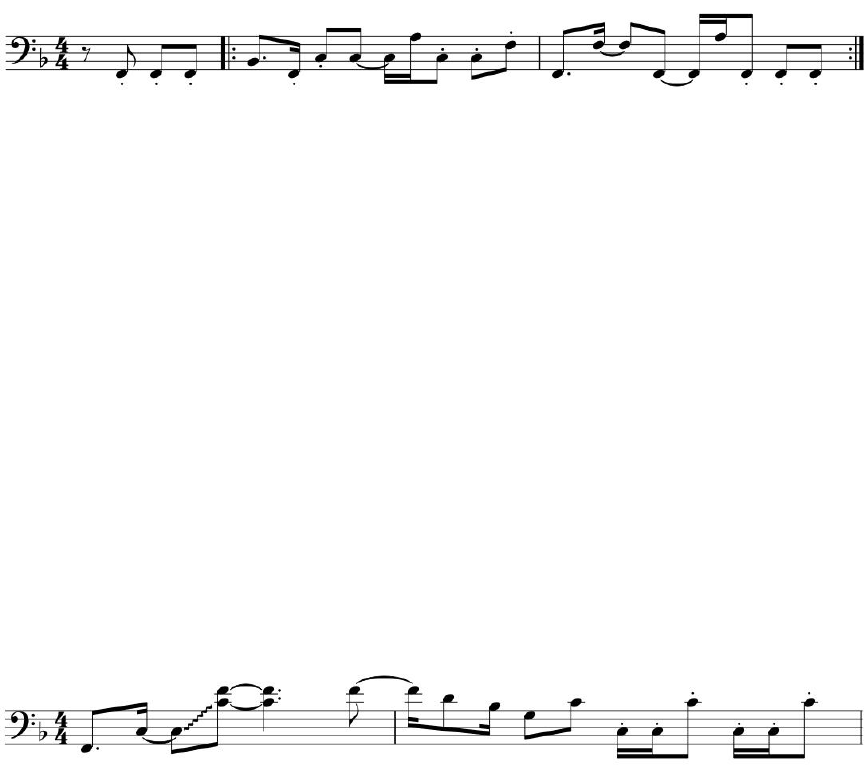

verses, shown in Example 3.17, is heavily syncopated, accenting the upbeat of beat one

immediately after the downbeat, and again beginning with an eighth-note pickup.

Example 3.17 “Under African Skies” measures 5-8

40

During the choruses, shown in Example 3.18, Kumalo keeps the same general accent

pattern going, but embellishes the line by switching to a slap technique. There are also

several muted slapped notes added for percussive effect. The addition of muted eighth-

note triplet figures also adds a percussive cross rhythmic effect to the track.

Example 3.18 “Under African Skies” measures 29-32

The bass line of “Crazy Love, Vol. II” is one of the more traditional mbaqanga

bass lines present on the album. This is most likely due to the track being written by and

credited to bassist Lloyd Lelose, a member of guitarist Ray Phiri’s band Stimela. The

original bass line can be heard in an early demo version of this track included on the 25th

Anniversary Deluxe Edition of the album. While the album version is nearly identical to

this early version, there are some differences in the final product, mainly in the chorus.

The line in the verse, as is seen in Example 3.19, is a simple eighth-note subdivision in

12/8 time. The bass plays a simpler version of what the lead guitar is doing by outlining

the triads within the I-ii-V progression. The staccato played in the second grouping of

three in the second bar of the bass line creates a natural syncopated accent that stands out

from the rest of the line, which keeps a fairly steady pulse while dividing the 12/8 pattern.

41

Example 3.19 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 5-6

The chorus of this track features a syncopated bass line, shown in Example 3.20, that

emphasizes the upbeat of the second grouping of three in the compound meter. There is

also a slide to the octave F in the second bar of the chorus which provides a syncopated

pickup to the third bar. This track also features a key change between the verses and

choruses, with the verses being centered on G major and the choruses on F major. This is

another example of the type of tonality shift common within traditional South African

music.

Example 3.20 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 31-34

In the later choruses of the track, there is a variation of the bass line with two added notes

at the end of the first and third bars, shown in Example 3.21.

Example 3.21 “Crazy Love, Vol. II” measures 79-82

42

As can be seen within the previous examples, the role of the instrument is

fundamentally different from the typical role of the instrument in the American pop style

of Simon’s previous music. Much of this difference has to do with rhythmic elements of

these bass lines, as well as differences in how the instrument is used in mbaqanga

compositions. While an American pop bass line may simply provide a pulse with the kick

drum, these lines rarely play anything that is less rhythmically complex than what the

drum kit is playing. During moments on the record where the bass is providing a

supportive role, it is still almost always playing some sort of syncopated subdivision. In

the moments where the bass stands out melodically, the lines, while still often syncopated

and rhythmically complex, draw from the melodic traditions of South African vocal

music. The ways in which the instrument interacts with other members of the ensembles

in both cases also creates the distinct rhythmic interplay common in South African music.

As a result of these elements, the bass acts as a stand-out element of what gives

Graceland its distinct sound. While the bass lines and tracks retain their South African

elements, Simon’s songwriting combines them with American pop melodies and song

forms, allowing these distinct bass lines to contribute to a more accessible sound while

remaining authentically South African. Though it cannot be entirely attributed to the bass

lines, Simon’s work following Graceland featured the instrument in a role much closer to

the South African style of playing on many tracks, incorporating similar rhythmic and

melodic elements into songs that were closer to Simon’s American singer-songwriter

style.

44

Chapter Four:

The Influence of Graceland’s Bass Lines on Simon’s Later Work

In both studio and live settings following the release of Graceland, the influence

of the record’s bass lines continued to affect Simon’s overall sound. When the time came

to follow up Graceland, Simon began writing what would become The Rhythm of the

Saints, continuing on a similar path as Graceland by adding Brazil and West Africa to the

list of musical influences after conversations with musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie,

Eddie Palmieri, and Brazilian percussionist Milton Nascimento about how percussion

instruments migrated from Africa to Central and South America. While some Graceland

musicians, including Kumalo, returned to play on the album, Simon’s approach was

broader and thus included other players from outside of South Africa, mainly through the

use of the Banda Olodum, a Brazilian percussion ensemble whose drumming would

become the backbone of most of the album’s arrangements (Carlin 2016, 312-313). Also

featured on bass throughout many of the album’s tracks is Cameroonian bassist Armand

Sabal-Lecco, whose virtuosic playing and heavily rhythmic slap playing stands out nearly

as strongly as Kumalo’s playing on Graceland (Simon 1990).

While the general concept for the album is similar to Graceland, the sound is

much less rooted in pop music and more centered on traditional sounds, as the album’s

title itself is based on “the traditional belief that the holy spirit was inside drums that

were used in various religious rituals and rites in Africa and Brazil” (Hilburn 2018,

45

293). The album also features some of Simon’s most rhythmically complex writing,

viewed as a step away from the simplicity of Graceland and described in a Rolling Stone

interview from the album’s release quoted in Homeward Bound as “aggressively

impressionistic and nonlinear” (Carlin 2016, 297). This is apparent on tracks such as

“Further to Fly,” which features a flowing 6/8 pulse driven by syncopated hand drums

and short repetitive guitar lines, as well as “The Cool, Cool River” with dizzying 9/8

guitar and bass lines that, along with the percussion and Simon’s vocal, create a

somewhat ambiguous pulse during the track’s verses. While mbaqanga is no longer the

primary musical influence on The Rhythm of the Saints, aspects of the genre do appear in

certain instances throughout the album. For example, the song “Proof” features a fast

12/8 mbaqanga feel not unlike “Crazy Love, Vol. II,” and the fretless bass playing on

the track sits comfortably within the melodic style Kumalo had played on many

Graceland tracks. The track also features melodic fretless sliding similar to “The Boy in

the Bubble,” among other Graceland tracks. Much of Sabal-Lecco’s playing also

incorporates similar elements of Kumalo’s style on Graceland, including syncopated

slap lines on “She Moves On” (Simon 1990). Though there are slight differences in the

styles of playing between the bassists, the way in which Simon utilizes the instrument in

his arrangements on these two records remains mostly the same, with the electric bass

acting as a key rhythmic element as well as occasionally providing countermelodic lines.

Following the release of The Rhythm of the Saints, Simon embarked on the “Born

at the Right Time” world tour, which included a show in Central Park that would be

recorded and released as a live album, Paul Simon’s Concert in the Park (Hilburn 2018,

298). The album features six tracks from The Rhythm of the Saints, as well as many of

46

Simon’s classic hits spanning his entire career from his days with Art Garfunkel up to

Graceland. Because Simon had been touring with a band of musicians from Graceland

and The Rhythm of the Saints, the new arrangements of the tracks feature elements of the

sounds from both albums. This is especially true within the bass lines, which are re-

imagined to follow the roles of those albums which contrast to the American pop style

lines of their recorded versions.

An example of this can be heard on the album’s live version of Simon’s 1973 hit

“Kodachrome,” an acoustic guitar-driven pop track from the album There Goes Rhymin’

Simon. While the original opens with finger-picked guitar chords, the Central Park

arrangement instead begins with a blistering sixteenth-note electric bass melody played

by Armand Sabal-Lecco. Instead of the typical backing instrumental from the studio

version, the live version is played in a style including elements from mbaqanga as well as

ska, while the roles of the guitars, bass, percussion, and horns are all similar to their roles

on Graceland. Throughout the track, the bass melody returns as a main melodic figure for

the song, similarly to melodic lines present on Graceland. This newer style of