Southern Illinois University Carbondale

OpenSIUC

e Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul

Simon Public Policy Institute)

Paul Simon Public Policy Institute

2-2013

President Obama's Victories in Illinois: 2012

Compared to 2008

John S. Jackson

Southern Illinois University Carbondale, jsjacson@siu.edu

Follow this and additional works at: hp://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers

is is paper #34.

is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in e

Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute) by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information,

please contact [email protected].edu.

Recommended Citation

Jackson, John S., "President Obama's Victories in Illinois: 2012 Compared to 2008" (2013). e Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the

Paul Simon Public Policy Institute). Paper 34.

hp://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers/34

1

THE SIMON REVIEW

President Obama’s Victories in Illinois:

2012 Compared to 2008

By: John S. Jackson

Paper #34

February 2013

A Publication of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute

Author’s Note: The author would like to thank Cary Bryant, Ashley Rippentrop, Shanara

Bush, and David Lynch for their invaluable assistance in the research for this paper.

2

President Obama’s Victories in Illinois: 2012 Compared to 2008

By: John S. Jackson Paul Simon Public Policy Institute

Abstract: This paper describes and analyzes President Obama’s 2012 election victory in

Illinois and compares it to his earlier victory in 2008 in his home state. It also extends the

analysis back through the 2004 and 2000 presidential elections and shows how those results

were similar and where they differed. It primarily relies on the county and county election

returns supplemented by U. S. Census data as the unit of analysis. The paper sets Illinois into

a national electoral context describing what is happening in an era of deep partisan

polarization coupled with the prospects for a partisan realignment.

Introduction

Barack Obama is the first President elected directly from Illinois since both Abraham Lincoln

and Ulysses S. Grant won two elections each during the Civil War and its immediate aftermath

in the 1860s and 1870s. Other candidates from Illinois have run and been a factor in the

presidential sweepstakes such as Adlai E. Stevenson, II who ran twice and was twice defeated

by the same man, Dwight Eisenhower, in 1952 and 1956. We have also produced several viable

candidates who sought their party’s nomination unsuccessfully including John Anderson, Paul

Simon, and Phillip Crane. Adlai E. Stevenson was Cleveland’s Vice President in 1892 and John A.

Logan was James G. Blaine’s Vice Presidential running mate in 1884. However, Barack Obama is

the first candidate from Illinois to actually win the nomination, twice, and win the general

election, twice, since the Civil War era. As a producer of presidents Illinois is now somewhat

behind the three leaders, Virginia, New York, and Ohio but equal with Texas in the second tier

of states which have produced multiple presidents and who have had their careers shaped by

their state’s politics before climbing to national fame (Stanley and Niemi, 2010, 233-237).

Paul Simon’s influential book, Lincoln’s Preparation for Greatness, showed just how important

Lincoln’s experience in Illinois politics, especially his time in the Illinois General Assembly was in

shaping his views and values and his approach to governing in Washington (Simon, 1971). A

similar work on Obama would also conclude that his service in the Illinois General Assembly

was an important factor in shaping his views and political style and values. That period also

produced some indicators of how he might approach being president especially through the

seeking of bipartisan solutions to difficult problems and courting cooperation across the aisle.

His record in Illinois indicates that Obama is by nature a conciliator, a consensus seeker and

coalition builder and that was his major forte during his time in the Illinois legislature. It was

also his initial approach to the presidency although that changed as time went on and

experience with the Congress in a highly polarized and partisan era changed him by the

beginning of his second term. Likewise studying Obama’s three statewide victories in Illinois

3

politics provides some worthwhile clues as to where he had the most and least electoral appeal

in 2008 and 2012 and how he approached the very political task of building an electoral

majority in a large and diverse state like Illinois.

In 2006 I wrote a Simon Review paper documenting the rise of Barack Obama to a position of

power in Illinois politics via his winning the U. S. Senate seat in 2004 (Jackson, 2006). Later I

extended this analysis to Obama’s victory in Illinois in his first quest for the presidency (Jackson,

2009). Obama’s 2008 presidential nomination and subsequent election victory, one of nearly

landslide proportion in the Electoral College, was almost unprecedented for a candidate who

was as young and unknown on the national stage as he was at the time, and it was absolutely

unprecedented for a candidate with his racial identity to ascend to the White House while

defeating two of the most experienced and respected recent candidates, Hillary Clinton and

John McCain, one Democrat and one Republican, in the process.

The current paper is a continuation of that series documenting how Obama fared in his

presidential re-election race of 2012. At that point Obama was certainly no longer unknown

and his record in the management of the government, especially in regard to his management

of the economy, was the central point of contention in the 2012 general election. In addition,

the polarized state of American politics has been the major fact of political life in Washington

recently, especially after the gains of the Republican Party and its Tea Party faction in the 2010

mid-term elections (Levendusky, 2009; Fiorina, 2005; White, 2003).

When the Democrats lost control of the U. S. House and suffered reduced numbers in the

Senate after 2010, bipartisanship and conciliation largely became things of the past in the

Obama Administration, and it became much more difficult for the president to get any of his

major legislative priorities enacted in such a divided Congress. Partisan and ideological gridlock

and stalemate became much more the norm during the second half of Obama’s first term.

The national election was certainly a referendum on Obama’s stewardship of his office and of

the government, and the same was true in Illinois. This paper details how he did in Illinois in

2012 and how this election compared with his electoral record from 2008. Illinois has been a

typical state for national politics for a long time. One study based on U. S. Census data ranked

Illinois as “the most average state” in the union (Ohlemacher, 2007). Indeed, despite its

reputation as a leading blue or pro-Democratic state currently (Green, 2003; Green 2007),

Illinois is still one where either party can win statewide depending on the candidate and the

circumstances of the moment (Jackson, 2011).

In creating this longitudinal electoral record I hope to shed some light on the larger patterns of

both continuity and change in Illinois and national politics as illustrated by the Obama elections.

Obama’s record has been written in less than a decade since he first appeared on the state and

4

then the national scene and went on to achieve the kind of success only realized by a handful of

presidents who have been elected to two terms. In fact, of the 43 presidents we have had in

the United States prior to Obama, only seventeen, or less than half, have been elected to a

second term. So, Obama has already joined select company from a very small universe which

begins with George Washington at the founding of the Republic in 1789 and extends through

George W. Bush who prevailed in the first two elections of the 21

st

Century (Stanley and Niemi,

2010, 17-21).

Illinois certainly played a crucial role in shaping the political values and the career of the young

Barack Obama, not only providing him his first home and profession as a new college graduate

and later a new law school graduate, but also providing him the political base to move from

South Side Chicago community organizer and constitutional law professor at the University of

Chicago, to the Illinois State Senate, and then to the United States Senate, all before he had

reached his 45

th

birthday. For all the controversy which seemed to never die over his

birthplace, no one ever doubted that his political home was firmly planted in Illinois. That

grounding in Illinois was topped by an overwhelming popular election victory in 2008, both

nationally and in the state, and then confirmed by another popular vote victory, by a smaller

but still convincing margin in 2012.

On a common sense or conventional wisdom basis, one might think initially that there was

nothing at all unusual about a presidential candidate winning his home state. That is the most

common outcome in American presidential elections; and if a candidate is not carrying his

home state, preferably by a wide margin, then he is probably in some trouble nationally. While

carrying the home state is the norm, it is by no means a confirmed law of politics. There are

several recent examples of presidential candidates not carrying their home states. Al Gore was

elected U. S. Senator from Tennessee first in 1984 and then again by a larger margin in 1990

and he had been a four term Congressman before then. Yet in 2000 Gore failed to carry his

own state and thus lost the election to George W. Bush in a much disputed outcome involving a

537 official vote margin in Florida and the 5:4 vote of the U. S. Supreme Court. However, Gore

would not have even needed Florida if he had just carried Tennessee, which was not out of the

question since he and Bill Clinton together had carried both Tennessee and Arkansas in 1992

and 1996.

Or consider the case of Mitt Romney who lost the state he had served as Governor,

Massachusetts, which Obama won by a 63.20 percent margin in 2012. In addition, Romney lost

his native state, Michigan, the state where he was born and raised, and the state his father had

served as Governor, by a similar margin in 2012 when Obama carried Michigan by a 58.37

percent margin. Romney also had a second home in New Hampshire, which he repaired to

frequently to escape the rigors of the campaign trail during the 2012 election, and he also lost

5

New Hampshire by a narrow but still decisive 54.87 percent Obama margin. He also lost

California, another state where he had a home, by a wide margin. In summary, Mitt Romney

did not have a place where he could claim a home state advantage unless it was Utah where he

scored his biggest victory of the 2012 election with an overwhelming 74 percent of the popular

vote (David Wasserman, Redistricting web site, accessed Nov. 21, 2012, unofficial and partially

incomplete returns).

Going back in history, Adlai E. Stevenson, II ran twice against Dwight Eisenhower in both 1952

and 1956, and he lost Illinois both times. Illinois was Stevenson’s home state, the place he had

served as Governor, the place where he had built his political reputation and base, and he lost it

twice. Making it remarkably evident how much our politics have changed, it is even more

notable now to consider that Adlai Stevenson carried all of the states of the Deep South, while

losing Texas, Virginia, Florida and Tennessee, in both 1952 and 1956, and only losing the Deep

South’s Louisiana in 1956. The South was the Democratic base in that era. But Stevenson lost

Illinois both times. Times have certainly changed with the Deep South and the peripheral South

now forming the virtually unassailable bedrock of the Republican presidential core.

In 2012, Obama’s victory in Illinois was sizable although it was not greater than in his native

state of Hawaii or the District of Columbia and several other Northeastern and Midwestern

states which exceeded the percentage Obama gained in Illinois. These states are the latest

markers in the party realignment which has seen the Northeast and parts of the industrial

Midwest transformed from solidly favoring the Republicans in presidential elections to

providing the most promising base for Democrats in our current presidential politics.

For most of the 20

th

century Illinois was one of the most typical states from an overall

demographic and political perspective. Illinois almost always reflects the national vote and in

the 20

th

Century; it only went against the national winner in 1916 when the state voted for

Charles Evans Hughes over the Democratic incumbent, Woodrow Wilson, and in 1976 Illinois

again swam against the national tide and voted for Gerald Ford over Jimmy Carter. Those were

the only two instances in the entire 20

th

Century when Illinois voted against the presidential

winner. More recently, in the 1980s Illinois voted for Reagan twice and for George H. W. Bush

in 1988. That was four consecutive wins for the Republicans. So, for that century, Illinois was a

competitive state where either party could win which both reflected and helped lead the

national trends in presidential politics.

In many important ways, Illinois politics are indicative of larger trends in national politics. In a

realigning era, Illinois has trended more and more firmly toward the Democratic Party and the

Republicans have lost significant ground in this state over the past two decades of presidential

and statewide elections. Since 1992 when Illinois went for Clinton, Illinois has been one of the

leading and most dependable components of any Democratic presidential candidate’s core

6

strength. Clinton won twice. Then Gore won Illinois in 2000; John Kerry won in 2004, and

Obama won in 2008 and 2012. While this is a consistently pro-Democratic victory outcome, it is

also worth noting that except for 2004, Illinois voted for the winner of the national popular vote

in every election since 1976 and in that respect can be considered “typical”. The contours of

Obama’s victory map illustrate that transition from Republican victories under Reagan and

George H. W. Bush to Democratic victories under Clinton and Obama.

Sports fans know that there is a definite home court advantage in basketball, baseball, hockey

and other sports, and ordinarily that analogy carries over to politics as well but not always. So

it is worthwhile to analyze how and where Obama fashioned his adopted home state victory in

both 2008 and in 2012 and what important trends in American politics are indicated by those

victories. That is the objective of this paper.

The Data Analysis

Let us begin by examining the size and scope of President Obama’s victory both nationally and

in Illinois. On the national level, Obama won a majority of the popular vote with approximately

51.03 percent of the total compared to 47.19 percent for Romney. This resulted from Obama’s

approximately 65,899,583 total votes to Romney’s 60,931,966 - a margin of almost five million

(http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/national.php?year=2012, accessed Jan. 11, 2013).

While the popular vote was somewhat close, the Electoral College vote was almost a blow out

for Obama. He beat Romney by a 332 to 206 vote margin, or a 62 percent Electoral College

victory. Obama carried 26 states, plus the District of Columbia, compared to 24 for Romney.

This provided only a narrow net state advantage to Obama; however, the president carried far

more of the larger states and he carried eight out of ten of the states originally considered to be

the most competitive, or “battleground” states which either candidate could have won and

where both candidates spent an extraordinary amount of time campaigning personally. For all

the enormous amount of time, energy and resources the Romney campaign poured into the

battleground states, he ultimately emerged with victories in only North Carolina and Indiana as

two take-away states from the 2008 Obama Electoral College margin of 365 to 173 over John

McCain.

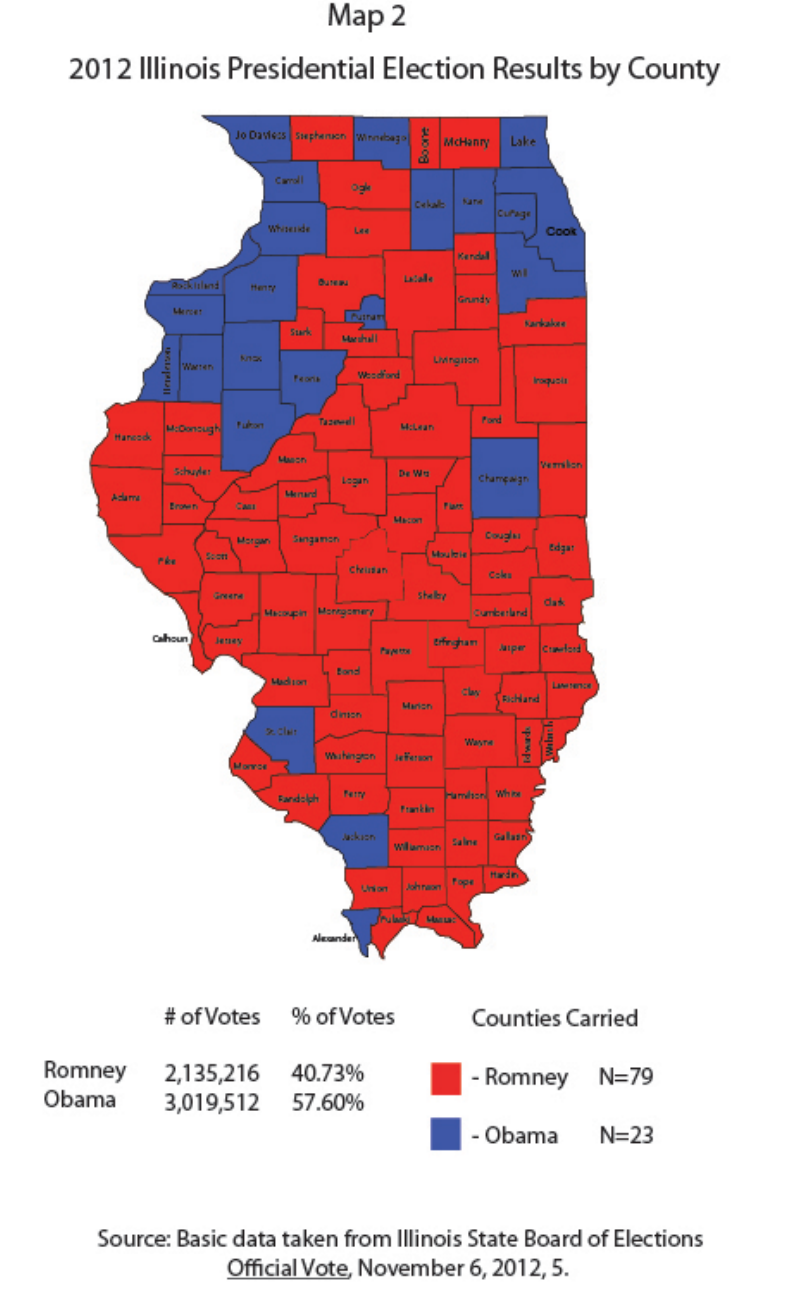

This map illustrates the way the Electoral College normally works. That is, a fairly narrow

victory in the popular vote, especially if it exceeds a majority at 50 to 51 percent, usually

translates into a much larger Electoral College victory. The 2012 election provided another case

reinforcing that general rule. Supporters of the Electoral College contend that this Electoral

College magnification of the majority is good for the system. They argue that it is effective in

bestowing a sense of legitimacy and claiming rights on an electoral mandate if the Electoral

7

College vote victory is by a significantly wide margin. Map 1 provides the graphic display of

those national popular and electoral vote returns.

The national results then provide the context for analyzing the Illinois results. Obama carried

Illinois with 57.60 percent of the total popular vote. This was in comparison with the 61.92

percent he carried Illinois by in 2008 (Illinois State Board of Elections, 2013 and 2008). This

marked a decline in the Obama popular vote in Illinois of 4.32 percent between 2008 and 2012.

So, in that sense, Obama actually lost some ground in Illinois between 2008 and 2012, which

was also true nationally when his popular vote margin declined from 52.9 percent to 51.03

percent or a net decline of 1.87 percent nationally (Stanley and Niemi, 2010, 25; David

Liep,http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/national.php?year=2012, accessed, January 11,

2013). Thus, Obama lost a somewhat larger percentage of the Illinois popular vote than he did

of the national popular vote in 2012. The economic situation which had worked in Obama’s

8

favor in 2008 had less positive impact for him in 2012 even though it was probably overall still a

net positive, narrowly, according to the polls.

In some respects the geographical totals were mirrored at the state level if you use the county

as the unit of analysis. The analogy is not entirely apt since the counties are not constitutionally

or legally the same thing as the states in the Electoral College. Ultimately it does not matter

much how many counties a candidate carries, but it does matter critically how many states, and

which states, the candidate for president carries. Nevertheless, counties are important units of

local government and they are key party organizational building blocks and political rallying

points as well. The county court houses usually are filled with officials who are the backbone of

their local party organizations (Jackson, 2011). In this sense, the counties are an effective

window onto the world of local politics. They represent grassroots leaders and average voters

down at a level where most people live and receive governmental services and where they pay

significant amounts of their local taxes.

In addition, most counties are embedded in and reflect their own particular political culture. In

most states, certainly in Illinois, there are counties which are well known as Democratic or

Republican strongholds where the candidates at the top of the ticket do not seem to matter

much as these counties vote routinely for their traditional party favorite no matter what the

national or statewide trends may be at the time. There are others which can be relied on as

marginal or swing counties where the results change from election to election and immediately

reflect the political tides of the moment and which are also potentially involved in longer term

transitions from one political party to another. If you are going to capture the picture of long

term secular changes in American politics, county level voting returns are a very good place to

document those processes in action. For all those reasons, the counties are important units of

analysis for any election, including the presidential elections.

9

10

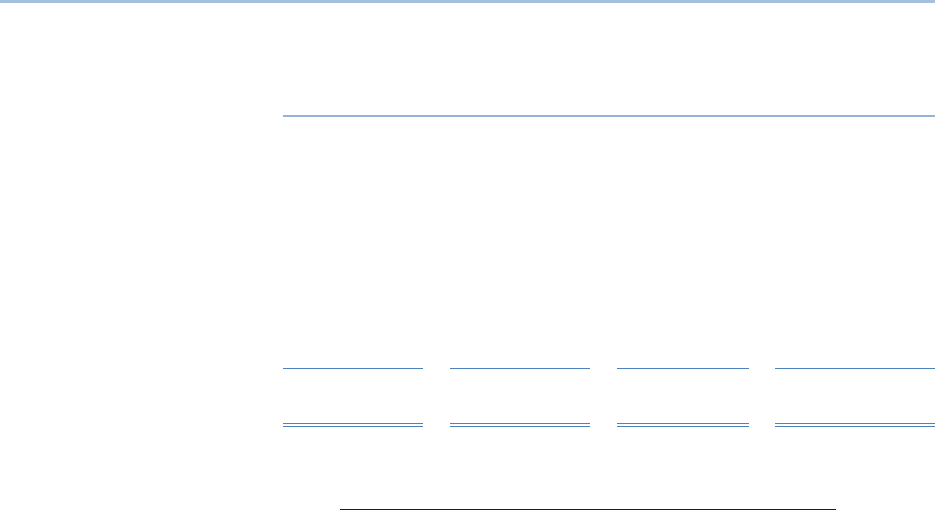

Map 2 provides the results by county for the 2012 presidential election in Illinois. It is

immediately evident from this table that Obama carried only 23 counties compared to 79 for

Romney. Obama carried northeastern Illinois, northwestern Illinois, and a smattering of other

counties. Thus, in terms of sheer geography, the map of Illinois had far more red territory than

blue showing on it on Tuesday night, November 6

th

. Appendix A provides the complete 2012

voting returns for the two major parties for each Illinois county.

Table 1 displays the 2012 election return data divided into the traditional three major

geographical sections of the state, i.e. Chicago and Cook County, the five Collar Counties which

form the suburban ring around Chicago, and the remaining 96 counties which are routinely

referred to as “Downstate.”

Cook County accounts for 40 percent of the total population in the state. Obviously it is the

major prize in any statewide contest no matter which year and what candidates are involved.

In 2012 Cook County provided a large vote total margin of 1,488,537 for Obama and 495,542

for Romney (Illinois State Board of Elections, website, accessed, January 9, 2013). Obviously,

Cook County and Chicago were absolutely essential keys to the size of the statewide victory for

Obama. However, contrary to popular belief in Downstate Illinois, they were certainly not the

whole story. The popular vote total for Obama from Cook County was 49.30 percent of his

statewide popular vote margin. In other words, with 40 percent of the state’s population, Cook

County provided almost half of Obama’s total votes in Illinois.

The additional Obama margin of victory in the popular vote came especially and notably from

the five Collar Counties. Obama carried four of those five, losing only McHenry narrowly. In

those five counties combined Obama scored a 647,575 to 613,712 popular vote margin victory

over Romney or a 33,863 Obama vote margin. This margin was certainly one of the major

explanations for the Obama victory in his home state in 2012. No Republican candidate can

afford a net loss in the five Collar Counties, much less coming out of the collars with an almost

34,000 vote deficit. In order to be a viable statewide candidate, a Republican needs to win the

Collar Counties, and even win by a comfortable margin, in order to have a chance against the

Democrats.

11

Table 1

The five Collar Counties, Cook County, and Downstate Contributions

Obama

votes

Percent of

Obama's

Total

Romney

votes

Percent of

Romney's

Total

Cook County

1,488,537

49.30

495,542

23.21

Five Collar Counties

647,575

21.45

613,712

28.74

Downstate

883,400

29.26

1,025,962

48.05

Total

3,019,512

100.00

2,135,216

100.00

The "Collar Counties" are Lake, McHenry, Kane, DuPage, and Will.

Source; U.S. Census. 2010. http://quickfacts.census.gov/gfd/states/17/17001.html

Accessed: Dec. 20, 2012

So, Obama won Cook County by a very wide margin of almost one million votes. He then took

the Collar Counties with almost 34,000 vote margin. This left only Downstate where Romney

ran much better; however, he did not have enough total votes out of Downstate to come

anywhere close to winning statewide. As Table 1 indicates, Romney took an aggregate of

1,0265,962 total votes from Downstate compared to 883,400 for Obama. This is an advantage

of 142,562 votes for Romney provided by Downstate. Ordinarily this would not be a bad vote

margin from Downstate for a Republican candidate. However, Romney’s Downstate advantage

was more than counterbalanced by the 1,026,858 vote advantage Obama enjoyed over

Romney in Cook and the suburban counties. As Table 1 shows, Romney received 48.28 percent

of his statewide total from Downstate while Obama received only 29.26 percent of his total

vote from Downstate. Realistically there are just not enough votes in the 96 Downstate

Counties for any Republican to make up the deficits Romney sustained in Cook and the five

Collar Counties.

Table 2 expands the scope of the inquiry to the fifteen most populated counties in Illinois. As

the summary statistics on the table indicate, these fifteen topmost counties are where most of

the people live in Illinois. They account for, in total, 10,168,148 of the total of 12,830,632

people who were counted by the U. S. Census in 2010. Thus, 79.24 percent of all the Prairie

12

State’s people are found in only fifteen of its one hundred and two total counties. Of those top

fifteen, Obama carried ten counties and Romney carried only five. The behemoth is Cook

County which accounts for 5,194,675 of the total of almost thirteen million people in the state.

However, even if one leaves Cook County out of the equation, Obama still enjoyed a 4 to 1 ratio

over Romney in the fifteen most populated counties (Data taken from U. S. Census, 2010;

http:/quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/17007.html, accessed December 18, 2012).

Table 2

Top Fifteen Largest Counties in Illinois

2010

Population

2012 Presidential

vote

Obama

Vote

Romney

Vote

Cook

5,194,675

Obama

1,488,537

495,542

*

DuPage

916,924

Obama

199,460

195,046

*

Lake

703,462

Obama

153,757

129,764

*

Will

677,560

Obama

144,229

128,969

*

Kane

515,269

Obama

90,332

88,335

*

McHenry

308,760

Romney

59,797

71,598

Winnebago

295,266

Obama

61,732

55,138

St. Clair

270,056

Obama

67,285

50,125

Madison

269,282

Romney

58,922

60,608

Champaign

201,081

Obama

40,831

35,312

Sangamon

197,465

Romney

42,107

50,225

Peoria

186,494

Obama

40,209

36,774

McLean

169,572

Romney

31,883

39,947

Rock Island

147,546

Obama

39,157

24,934

Kendall

114,736

Romney

22,471

24,047

Total:

10,168,148

2,540,709

1,486,364

Population Obama Counties

9,108,333

Population Romney Counties

1,059,815

*

Designates "Collar Counties"

As the table indicates, the ten counties which Obama carried in 2012 account for a total of

9,108,333 people while the Romney counties only accounted for 1,059,815 people. In

summary, approximately ninety percent of the total population in the urban counties lived in

Obama counties while only ten percent of the population of the urban counties was in the

13

predominantly Romney territory. You have to descend to the sixth largest county, McHenry, to

get to the first and largest Romney County, and it is the only one of the Collar Counties to go for

the Republican. Next largest is Madison County in the Metro-East area around St. Louis and

then Sangamon County, home of the state capital, both of which are counties in the circa

200,000 to 300,000 population range which also provided Romney with a victory. Finally there

were McLean County in Central Illinois and Kendall County an exurb county in Northeastern

Illinois which fell into the Romney column and both of these counties were well under 200,000

in population.

Table 2 focuses on the fifteen largest counties and details just how severe Romney’s

disadvantages were in those big counties in Illinois. The larger counties, outside Cook and the

Collar Counties voted for Obama by 404,597 compared to 377,110 for Romney, or a 27,487

total advantage to Obama. When coupled with Obama’s margin in the Cook and the Collar

Counties displayed in Table 1, you get a popular vote total of 2,540,709 for Obama compared to

1,486,364 for Romney. Thus, the fifteen largest counties in Illinois provided a net margin of

1,054,345 for Obama’s total large county vote victory in Illinois in 2012.

Obviously then, Romney had a major problem in the urban areas although one could argue that

Obama, likewise, had a problem in the rural areas. In the presidential sweepstakes, however, it

is votes and population which ultimately count and the numbers are in the larger cities and

counties. The die was cast in the urban counties and there was virtually no way the

remaining 87 smaller and more rural counties could have overcome that margin which

favored Obama so heavily no matter how overwhelmingly they voted for Romney.

In recognition of the fact that Romney won far more counties, and more congressional districts

that Obama did in 2012, some Republican leaders in states where they control the governor’s

office and both houses of the legislature are now pushing a plan to allocate that state’s

Electoral College votes on basis of the congressional district winner. This is currently the law in

Maine and Nebraska. If this were done in large states like Florida, Virginia and Michigan, it

could significantly tilt the playing field in favor of future Republican presidential candidates.

While these are only Illinois data, this pattern existed all across the nation. As a matter of gross

geographic analysis, the central cities and the surrounding metropolitan areas, with some

exceptions in the suburban South, tended to vote heavily for Obama while the more rural the

area the more likely it was to vote for Romney. This urban-rural divide is large and has been

growing ever since the South broke from the Democratic Party starting in the 1960s and 1970s

and realigned itself with the Republicans. This pattern already existed in many parts of the

Midwest and the West contributing to and reinforcing the national’s partisan and ideological

polarization trends which have been on the increase for the past two decades.

14

Thus, the rural areas of Illinois provided their votes disproportionately to Governor Romney just

as they did nationally. This was not, however, a new voting pattern in Illinois. In many of the

rural counties they have been voting for the Republicans and even before that for the Whigs

since before the Civil War when Abraham Lincoln was still running as a Whig and then running

as the standard-bearer for the new Republican Party in 1860 and 1864. The red counties on

Map 2 are where the bedrock strength of the Republican Party has always been in Illinois and

there is voting continuity going back for generations which is very rarely broken in national or

state election returns (Key, 1966, chapter 8). This pattern, too, is a part of the historic voting

pattern for much of the Midwest which was once a crucial part of the backbone of the

Republican Party. These counties provide the foundation for the political continuity which is so

evident in much of American electoral politics, and particularly in the more rural areas.

Providing the voting returns at the county level, as Map 2 and Tables 1 and 2 do, helps to make

the point more graphically. The data are reported to the State Board of Elections by County

Clerks and other election officials and are readily available for analysis. However, the point

goes beyond analytical convenience. A part of the thesis of this paper is that the counties are

important political units in Illinois and they constitute a slice of the larger regional political

culture where the habits and patterns of voting exhibit a high level of consistency and

continuity from election to election and even generation to generation.

In fact, counties themselves also have distinct political cultures and histories and these political

norms make it much more likely that their aggregate voting returns will resemble one another

across time and elections. However, there is also room for change especially if they are

dynamic economically and there is marked in and out migration in the counties and if their

demographics are changing significantly. It is also true that a strong statewide or national

candidate can come along occasionally and help disrupt the established voting patterns at the

county and regional levels especially in high stimulus and high turnout elections.

Importantly for the future of both parties in Illinois, Obama made serious inroads in suburban

Cook County and the traditionally Republican Collar Counties around Chicago in 2008 and he

solidified those gains in 2012. Obama carried Cook County handily and four of the five

traditional Collar Counties in 2012 even when his statewide totals declined. From his 2008

Collar County coalition in 2012 Obama only lost McHenry, which is the far northwest of the

Collar Counties and home of the exurban voters who have reliably voted Republican even

though 2008 was an exception when Obama also carried McHenry County. If the Collar

Counties are trending more Democratic, and these results as well as earlier research published

in The Simon Review indicate they are, this is an important emerging political development for

Illinois (Jackson, 2004; Jackson and Gottemoller, 2007).

15

As Colby and Green argued in 1986, Downstate Illinois used to be the key to Illinois as the

suburbs voted reliably for the Republicans and Central City Chicago voted heavily for the

Democrats (Colby and Green, 1986). Today, suburban Cook and the Collar Counties are where

statewide candidates make it or get broken in Illinois politics. The Collar Counties are growing;

Central City Chicago has declined as a proportion of the statewide total; and Downstate has

both growing and declining counties, but on balance it has remained stable as a percentage of

the total state population. The suburbs are where most of the growth is and the balance of

power now resides there in Illinois politics. They have also become more diverse, especially

because of the influx of new Hispanic residents and other ethnic groups as well.

Recently the Democrats have made steady gains in those areas. In 2010 they were the keys to

the split decision realized by Republican Mark Kirk running for the U. S. Senate and for

Democrat Pat Quinn running for Governor (Jackson, 2011). Both Senator Kirk and Governor

Quinn’s victories statewide depended notably on their appeal to the suburbs. Those split

decisions were especially powered by the more moderate and Independent and split-ticket

voters in the Collar Counties. Those areas also significantly boosted the totals for Obama in

both 2008 and 2012.

It is evident that the northern and especially the northeastern counties, particularly Cook and

the Collar Counties, were the backbone of the Obama victory in Illinois because of their size.

He also carried some counties in the more urban and small city areas, such as Peoria, Rockford,

and the Quad Cities. These are areas where labor unions still maintain some political strength

and some are near to Iowa which was a battleground state with massive television spending

not present in Illinois otherwise.

Obama also ran well in St. Clair County which is an urban county in the Metro-East area around

St. Louis. There were only two counties in deep southern Illinois, Jackson and Alexander, which

voted for Obama. Jackson is the home of Southern Illinois University and Alexander has a large

African-American population. Those two deep southern counties have been long time bastions

of strength for the Democratic Party and they did not change their stripes for Romney.

Otherwise, the other southern Illinois results indicate quite a marked change since this area

used to be a stronghold for the Democratic Party and very dependable in voting for the

Democratic candidate for president as well as in statewide offices such as Governor (Leonard,

2010; Jackson and Leonard, 2011). Those counties, with the exception of Jackson and

Alexander, now have gone the same way as the once Solid South. They are still dependable

counties for the Democrats in some of the court house offices, but they routinely support

Republicans for Governor and for President.

16

This bifurcation of party allegiance or “split level” party identification is the same phenomenon

which was exhibited in the South before its transition into a predominantly one party region

over the past two decades or so. That is, the formerly loyal white Democrats voted massively

for the Democrats; then they migrated to be Independent and split-ticket voters, and then

changed fully into deeply loyal Republican voters, especially in national and state-wide

elections.

Elazar’s emphasis on the American South as the home to a “traditionalistic” political culture,

where deference to established social hierarchy and authority keep the social order stable and

in power is applicable here and is a part of the dominant political culture in the southern

sections of the state (Elazar, 1972). Southern Illinois is becoming more like its neighbors to the

south rather than transitioning into the recent voting habits typical of the Midwest or its

neighbors to the north (Jackson and Leonard, 2011).

Interestingly this emerging affinity for Republican candidates and preference for cultural

conservatism over labor union loyalty and bread-and-butter economic issues now marks many

of the counties in southern Illinois just as it is the defining characteristics of politics in the Deep

South of the old Confederacy. Culturally much of southern Illinois is now more southern than

Midwestern in its values and voting habits as much of our public opinion polling data show

(Leonard, 2010; Jackson and Leonard, 2011). The partisan realignment of much of southern

Illinois in its presidential and statewide office voting patterns now resembles the realignment of

the once Solid South from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party which took place in the

1980s and 1990s and which is now so important in the national Republican Party’s coalition.

This trend is counterbalanced by the realignment of suburban Cook and the Collar Counties

which has favored the Democrats. Those areas, which were once much homogeneous on race,

class and ethnic grounds are being transformed by the movement of new people, often

especially Hispanics and other minorities, into those formerly predominantly white suburbs. As

that movement has grown, the prospects for the state’s Democratic Party to win in those more

diverse areas have also grown.

Comparisons of 2012 to 2008

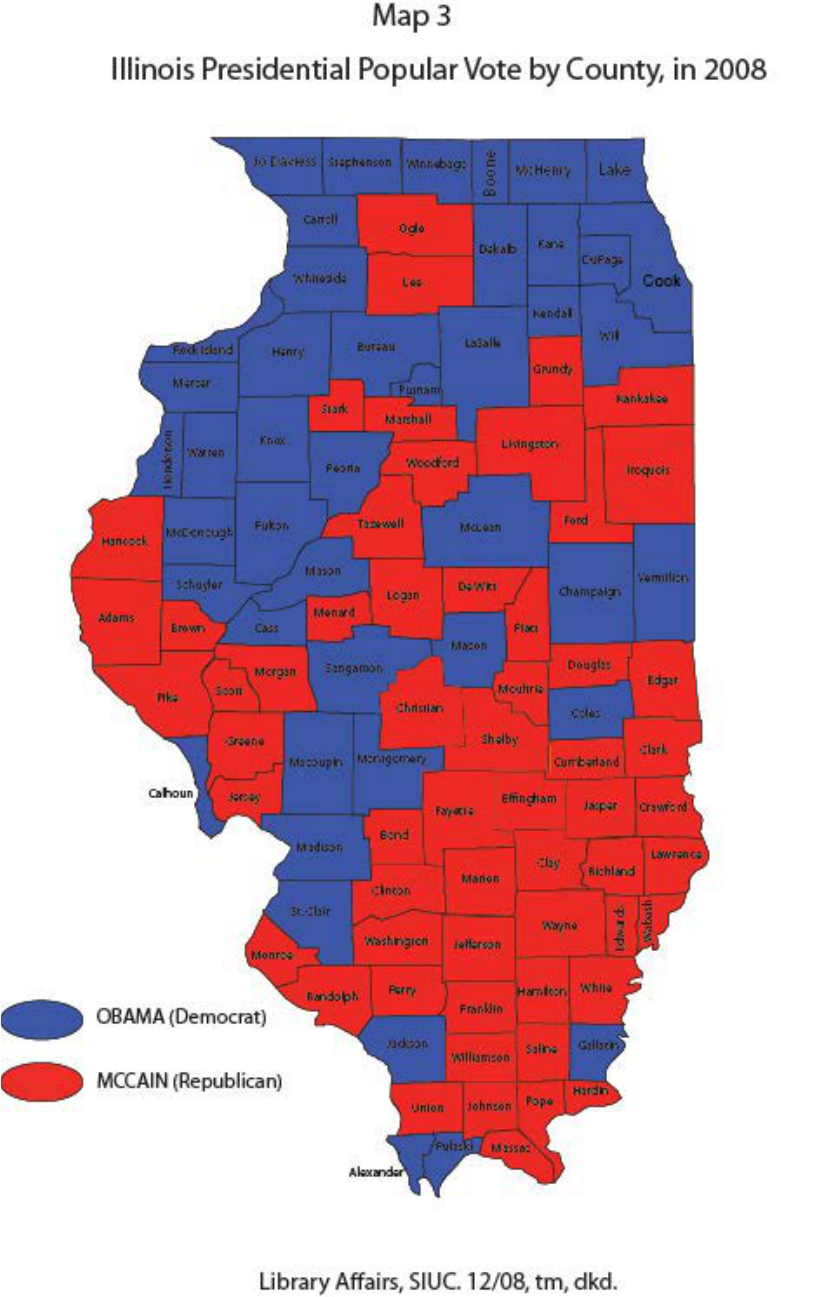

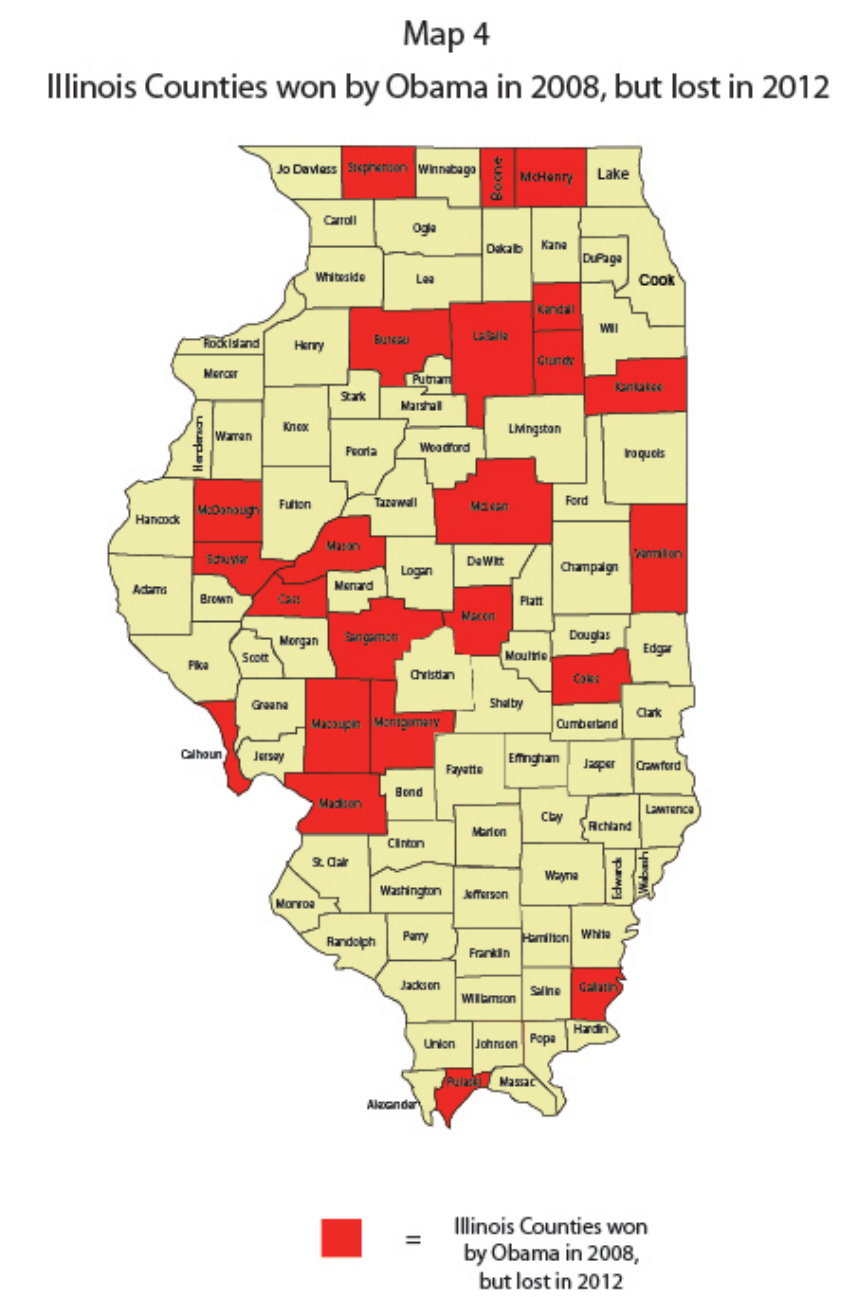

In Map 3 we examine the 2008 results and then in Map 4 we provide the comparisons by

county for the Obama versus McCain battle in 2008 and the Obama versus Romney contest in

2012. There is both considerable continuity and significant change evident from the

comparisons of the presidential election results for these two years.

17

18

Map 3 provides the color coded chart of the county by county returns for Obama versus

McCain in 2008 (Jackson, 2009). It shows that Obama carried 46 counties out of the total of

102 counties, or in other words, Obama carried slightly under half of the counties in Illinois

that year. This map shows the 2008 results were much more evenly divided geographically

between the red and blue counties with almost half of the total geography of the state in either

camp. This is more like what one would expect if the home court advantage was especially

working to Obama’s advantage in 2008 as it was. In general most Illinois voters of all

persuasions were proud of their native son and proud of the state for offering the nation the

potential to elect the first African-American to the lofty position of president of the United

States. Undoubtedly there was the familiar partisan division here with the Democrats voting

very heavily for Obama, and the Republicans voting for their own nominee, John McCain, with

the Independents split but leaning disproportionately toward Obama. However, even those

who did not vote for him tended to think well of Obama in 2008 and the state could proud of its

history of racial tolerance in its voting habits. For example, Illinois is the only state in the

modern era to have elected two African Americans, Barack Obama and Carol Mosley Braun to

be United States Senators with a third, Roland Burris, appointed to that position to fill Obama’s

remaining term.

19

20

By 2012, this situation had changed. The party lines were more prominent and the racial divide

was overlaid with ideological and geographical divisions. The old familiar Illinois regionalism

had returned, and the partisan and ideological polarization had hardened in the fires of political

conflict which marked Obama’s first term in the White House. While Illinois by a sizable

majority stayed in the Obama column, Map 4 shows the geographical distribution of the vote

for Obama versus Romney and then provides an overlay of the Obama versus McCain results.

As is evident from Map 4, Obama only carried a total of 23 counties in 2012 as compared to

46 in 2008. In other words in 2012 he lost half of the counties, or 23 counties he had carried

in 2008. Map 4 documents those counties graphically. In general most of them are in central

and northern Illinois. Two of the Obama losses also were in the traditional Democratic

strongholds of Gallatin and Pulaski in southern Illinois. Those counties where Obama lost the

presidential race in his home state in 2012 are mostly the competitive or swing counties and

some are traditionally Republican counties which he was able to attract temporarily in 2008 but

was not able to hold onto in 2012. Undoubtedly this loss was due in large part to the impact the

Great Recession had on Illinois as a state and to the toll it took on the president’s support and

job approval in Illinois and the nation after almost four years in office.

Nevertheless, although Obama lost ground, he obviously did not lose the overall election in

Illinois in 2012. Indeed, he won rather handily taking 58.57 percent of the Illinois two-party

vote. Clearly geography is less important than population, and the larger the county in

population the more likely they were to vote for Obama in Illinois and nationally. Of course,

the reciprocal of that relationship is also true with the smaller and more rural the county, the

more likely it was to vote for Mitt Romney in 2012. That population based correlation has

been true in every election of the 21st Century starting with Bush versus Gore in 2000 and

extending through Bush versus Kerry in 2008 and Obama versus McCain in 2008.

This is not an entirely new phenomenon, but it is one of relatively recent origins extending only

as far back as the recent realignment of our national political alliances. This correlation

between the rural/urban division in this country and its aggregate voting behavior has been

true in presidential politics ever since the nation underwent a partisan realignment that started

in the 1950s and 1960s and intensified in the 1970s and 1980s. This was when the South left its

traditional home in the Democratic Party and over the course of about two decades migrated

into becoming as dependable a part of the Republican Party’s core constituency as the Solid

South had been for the Democrats from the Civil War era until the 1970s. This is one of the

most important changes in American politics in the last 150 years since the Republicans were

founded in the period of 1854 through 1860.

That realignment is complete at the national level and its contours are now evident in the

Illinois presidential voting returns presented in Map 3 and Map 4 just as they are in the national

21

returns available in other sources. That is, the Republican candidate won handily all across

southern Illinois in both 2008 and 2012. In 2012 Romney won heavily in the rural areas of

central and northern Illinois where Republicans had always been strong although some of those

counties had strayed over to vote for Obama instead of McCain in 2008.

Indeed, this national realignment may reflect a larger and almost universal political norm. That

is, the rural areas in virtually all developed nations, and often even underdeveloped areas, are

usually more traditional, more conservative, more parochial, and more likely to support the

parties of the right or the more conservative political parties than the urban areas are (Almond

and Verba, 1965; Almond and Coleman,1960; Bishop, 2008). Thus, what is true in the United

States in the first part of the 21

st

Century is also true and has been for generations in other

nations where people have been given the right to vote for their leaders in free elections.

One of the objectives of this paper is to unravel some of the important explanation for the

geographic differences which have been quite evident in American presidential politics. These

differences are a fundamental part of what divides politics in Illinois and they are also endemic

to the divisive and polarized politics now faced routinely in the nation as a whole. In Table 3 we

explore some of the possible independent variables which differentiate the typically Republican

counties from the typically Democratic counties and differentiate both from the swing counties

which provide the potential for change from election to election. These variables include: the

2010 population of the county, the percent white, percent Black, percent Hispanic, median

home value, per capita income, median house-hold income, and percent below the poverty

rate for each county.

The post-mortems on the 2012 presidential election featured demographic variables and

demographic changes and trends prominently as important popular explanations for why

Obama was re-elected and how he was able to fashion a comfortable victory which was

apparently very surprising to many political analysts, as well as to the Romney campaign itself.

Most prominently featured was the changing racial and ethnic make-up of the United States.

The day after the election analysts started focusing more intently on the reduced size of the

white electorate, the importance of growth in the Hispanic population, and the unexpectedly

large rate of turnout for African-American and younger voters. All of these are typically

important explanations for voting behavior which go all the way back to the classic American

Voter research from the early 1950s (Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes, 1956) and to the

classic Columbia University research team’s results from the early and mid-1940s (Berelson,

Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954). So, journalists and scholars alike have been using the major

demographic categories as personal characteristic explanations, or at least significant correlates

of the vote for the many decades since.

22

However, this is largely an individual level of analysis explanation. We are using a somewhat

different approach when we utilize the county as the unit of analysis and we have to be careful

not to over interpret the demographic correlations. However, the basic argument of this paper,

like many others in this tradition, is that the county, or any other aggregate data level of

analysis, can provide important indicators of the geographic milieu and the political culture

context in which individual voters live and work. This argument is spelled out in an earlier work

in more detail and with significant data provided on the partisanship of county level officials for

the period of 1975 through 2010 (Jackson, 2011). Thus, this voting behavior tradition, which

goes all the way back to the seminal work of V. O. Key, is also an important adjunct to our

understanding of our state or the nation’s politics (Key, 1949, 1955, 1966). That is the approach

taken in Table 3.

23

Table 3

Demographics of Presidential Vote by County Political Reward

2010

Population

Percent

White

Percent

Black

Percent

Hispani

c

Median

Home

Value

Per

Capita

Income

Median

Household

Income

Percen

t

below

Povert

y

Counties

Won by

Obama in

2012 also

won by

Obama in

2008

415,933

85.8

9.4

8.9

$143,987

$

25,993

$

51,519

14.0

Counties

Carried by

Obama in

2008 and

Lost by

Obama in

2012

82,111

93.2

6.6

5.8

$117,448

$

24,605

$ 49,732

14.1

Counties

won by

Romney in

2012 and

by McCain

in 2008

24,653

93.7

2.9

2.2

$ 92,470

$

22,932

$ 46,696

12.5

Scholars and political analysts have been predicting an ideological and partisan realignment of

American politics for generations (Key, 1955; Burnham, 1975; Phillips, 1969; Judis and Teixeria,

2002). Partisan realignments are constituted by both individual and aggregate, or cohort group

changes which in total constitute a net shift from one political party to the other. Or

alternatively, there is a net shift which leaves the same party in the majority; however, it is a

new and differently constituted majority coalition. That is the short hand version of the shift in

voting allegiance that took place in recent American politics.

Table 3 starts with the racial and ethnic compositions of the Illinois counties as they are divided

into the three types of election results provided by the 2008 versus 2010 presidential results.

24

First, and most importantly, the consistently loyal Democratic counties were the large

counties with an average 2010 population of 415,933, while the consistently loyal Republican

counties, that is, those which voted for both McCain in 2008 and Romney in 2012 were the

smaller counties with an average population of only 24,653 people. The swing or more

marginal counties which voted for Obama in 2008 and for Romney in 2012 fit neatly in-between

with an average population of 82,111.

As expected the Obama counties in 2008 and 2010 are much more diverse racially and

ethnically than the Romney and McCain counties are. That is, those consistently loyal

Democratic counties which voted for Obama in both 2012 and 2008 were 85.8 percent white,

9.4 percent black, and 8.9 percent Hispanic. Those which were consistently Republican, voting

for both John McCain and Mitt Romney were also much more homogeneous with 93.7 percent

white, 2.9 percent black, and only 2.2 percent Hispanic. Those which split between voting for

Obama in 2008 but voting for Romney in 2012 again fell neatly in between. They were 93.2

percent white, 6.6 percent black, and 5.8 percent Hispanic. In the social sciences one rarely

encounters empirical data where the pattern is clearer than that found in Table 3.

These aggregate level demographic results were certainly consonant with the national picture

and the analysis provided from the exit poll data provided by the national news organizations

(See for example: The Economist , November 10, 2012, 27-29; The Washington Post,

http;/www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/politics/2012-exit-polls/accessed, January 18,

2013). Those post-mortems stressed the racial and ethnic diversity of the Obama coalition and

how much his victory depended on the votes of those who in the past typically turned out at

lower rates and how well he ran among the black and brown voters while losing white voters by

a substantial margin. The turnout rate and the much vaunted Obama ground game were given

widespread credit for mobilizing the vote at historic levels among these populations in 2008

and then matching and in some states exceeding those levels again in 2012.

Another set of important demographic and socio-economic variables are those provided by

income, housing stock, and poverty rate data. These too are provided for the 2012 and 2008

results in Table 3. It is quite clear here that the median home value is highest in the

consistently Obama counties, second highest in the counties Obama carried only in 2008, and

lowest in the Romney counties. Likewise, median household income and per capita income

exhibited the same pattern. The affluent counties were also the Obama Counties, and the

next most affluent counties were the swing counties. The least prosperous counties, as

measured by median home value, per capita income and median household income, were also

the most loyal Republican Counties. (See Appendix B, C, and D for the data on each county).

The only minor variation on this overall pattern was in the percent below the poverty level

which was highest (at 14.1 percent) in the 2008 to 2012 swing counties, then next highest in the

25

consistently Democratic Counties (at 14.0 percent) and lowest (at 12.5 percent) in the

consistently Republican Counties. These differences are not great on the percent below

poverty indicator; however, as an overview they may indicate that consistently Republican

counties also have fewer people at the very lower end of the socio-economic scale, i.e. below

the poverty line. It may also suggest that the most affluent counties are also those with the

greatest income gaps (what the economists call the gini coefficient) and counter-intuitively they

are also the areas most likely to vote for the Democrats at the aggregate level (McCarty, Poole

and Rosenthal, 2006). That is certainly the case with Cook and some of the Collar Counties.

To recap, the richer and better housed counties and those with the highest per capita incomes

and highest median household income levels were also more likely to vote for Obama, and the

opposite is true for the Republican counties in both 2008 and 2012. Of course, this does not fit

the popular stereotypes that the Democrats are the party of the dependent populations, and

the Republicans are the party of the more prosperous and the wealthier people and areas.

This stereotype was reinforced somewhat during the presidential campaign when Romney in a

speech to an affluent audience at a $50,000 per ticket fundraiser in an up-scale enclave in

Florida talked about the “47%”who were dependent of governmental programs and not

persuadable to vote for him. This perspective is often capsulized in some of the media as “the

makers and the takers” who are supposed to mark the differences between the Republican and

the Democratic Party, but that is a vastly over stretched stereotype.

In addition, there are certainly predominantly rich areas and poor areas of the nation as well as

in the state of Illinois and those geographic differences have implications for public policy

making. It tends to be also true in Illinois that the rich areas disproportionately support the

state’s activities and public services which are more often needed and utilized in the poorer

areas.

As Gelman’s research at the national level shows, this transfer of income and wealth results

from the formula used in various governmental programs which tend to emphasize need and

ability to pay. This results in a national transfer of payments from what is generally called the

“blue states” to the “red states” which tend to be poorer at the aggregate level and filled with

more poor people individually. Gelman says the following in terms of his national findings:

At the state level, Democrats’ willingness to tax high earners and Republicans’

motivation to spend in poor states combine to yield large transfers from mostly

Democratic states in the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast to mostly Republican

states in the South and middle of the country. According to the Tax Foundation, the

poorest ten states (all of which George W. Bush carried in 2004) receive an average of

$1.60 in federal spending for every $1.00 they spend in federal taxes, while the richest

26

ten states (nine of which were won by John Kerry) receive only $0.80 on average

(Gelman, 2008, 62).

Other studies have consistently shown the same disparities in tax raising and spending patterns.

What is true nationally is also true of transfers from the rich to the poorer areas in Illinois

whether those poorer areas are on the south side of Chicago or in southern Illinois (Legislative

Research Unit, 1989). Thus, what is happening in the suburban parts of Cook County and the

five Collar Counties is particularly important in explaining Illinois politics.

Part of untangling the puzzle of the findings presented in Table 3 is rooted in the use of

aggregate versus individual level data. The analyst must be careful to avoid what statisticians

call the “ecological fallacy” or the inferring of individual level data from aggregate results

(Kramer, 1983). However, there is plenty of individual level survey and poll data to confirm the

correlation between socio-economic factors and voting. The basic generalization is that the

higher the socio-economic class, the more likely one is to vote Republican. Individual level

voting data consistently show that here are clearly tens of millions of poor, working class and

middle class people who vote for the Democrats; however, although they are not as numerous

there are also millions of the same categories who vote for the Republicans. There are millions

of comfortable and even rich Democrats just as is also true for the Republicans.

However, the argument of this paper and any analysis which takes advantage of aggregate data

is that the geographic context also matters to voters. If you take the aggregate level of analysis

provided by the county level of data, it is also clear that the geographic location and the

demographic characteristics of their communities are important in providing the context of

where the voters live, work and recreate. This life-style context is also important for their

politics influencing who their neighbors are, where they work, where they go for recreation and

go to church and their views on a wide variety of political and social issues. In general like-

minded people and those with similar economic status tend to cluster together geographically

(Brooks,2004; Bishop,2008).

Gelman describes the seemingly paradoxical nature of the individual versus aggregate level

results in the following terms:

Rich people in rich states are socially and economically more liberal than rich people in

poor states….What’s new is polarization- the increasingly ideological nature of

politics…the paradox is that polarization is going in one direction for voters and the

other direction for states. The resolution of the paradox is that the more polarized

playing field has driven rich conservative voters in poor states toward the Republicans

and rich liberals in rich states toward the Democrats, thus turning the South red and

New England and the West Coast blue and setting up a national map that is divided by

27

culture rather than class, with blue-collar West Virginia moving from solidly

Democratic…to safely Republican and suburban Connecticut going the other way

(Gelman, 2008, 4).

The dynamic Gelman describes derived from state level data also persists when the focus is

shifted to the county level in Illinois, and it illustrates some of the same party realigning trends

at the local level. Why is that cultural context so important and so much a part of the every-day

world of average voters?

Rural communities are just intrinsically different, in many ways that are politically important,

from the urban areas. People live in close proximity in the cities, and they tend to rub elbows

much more frequently and much more closely than those in the rural areas. They see public

services and public servants on a more up close and personal basis. The urbanite is more likely

to be aware of the dependence they have on governmental goods and services and to see

those services around them daily. Everything from keeping law and order on the streets, to

clearing the snow when the blizzards come, to operating the elevated or underground mass

transit systems on which millions depend to get to work or school are pretty clearly provided by

the government, and the supporting revenues have to be raised to pay for them.

Rural communities and their inhabitants almost live in a different world from their urban

counterparts. Sometimes it seems that the two populations may inhabit different political

planets. Rural dwellers are much more likely to take the concept of American individualism and

“American Exceptionalism” more personally (Kingdon, 1999). They are more likely to believe

themselves to be dependent on no one and to be more isolated from the trends and intrusions

of the global economy and the modern culture.

This may not be objectively true, as they and their jobs may well be dependent on the tides of

the global economy which beset workers universally today no matter where they live; however,

the rural resident is likely to believe that they are more independent and they do not have to

stand on the metro subway platform before taking the train to work each day. Driving a pickup

truck alone twenty five miles to work each day is a different experience. The path may be over

city, county, or state roads and highways, but the lesson of dependence on the government for

this service is not as direct or obvious. Going duck or quail hunting or fishing in a stock pond is

different from enjoying nature in the confines of Chicago’s Grant Park or walking along Lake

Michigan’s shore line. The cultural context is constantly reinforced by daily contacts and

personal interactions with peers, family and friends which tend to lead in a more conservative

direction.

Studies show that issues related to guns and gun control are particularly salient in the rural and

small town areas of the U. S. Rural dwellers are much more likely to value their guns and to

28

regard proposals for gun control to be anathema to them and to be something that urban

legislators are trying to unfairly foist off on a resistive rural population. This has been

particularly true in Illinois recently where the politics of gun control is a decidedly

geographically based fight. The rural residents and their representatives in the General

Assembly and in the Congress are staunch, even vehement advocates for the Second

Amendment and resist fiercely the various gun control measures which tend to emanate from

Chicago and which receive significant support from the legislators who represent suburban

Chicago. The battle over “concealed carry”, which found Illinois as the last holdout against

making concealed carry legal until a recent federal appellate court decision ordered the General

Assembly to fashion a change to the law, divides the state regionally and geographically more

than perhaps any other issue.

In addition, religion also divides the state and the nation in basic ways which are important

politically and which add to the ideological and partisan polarization which has developed in the

past two decades. It is well known in voting behavior that religious identification, and

especially frequency of church attendance, are important independent variables explaining

voting behavior (Flanigan and Zingale, 2006, 113-115 ). While there are certainly “mega-

churches” in the cities, the kinds of religious fervor and fundamentalism which have become

important components of the Republican coalition are more often found in rural and small

town America than in the cities (Putnam and Campbell, 2010). Conversely, the secularism and

cosmopolitan religious values and world views more often found in the cities are much more

likely to mark people who vote for the Democrats than for the Republicans (Wilcox, 2000;

Gelman, 2008, 78-79).

This is why the kinds of diversity documented in Table 3 is important in unraveling what is

taking place in the geographical, socio-economic and demographic polarization of American

politics and this case study of Illinois provides some important indicators of those larger

national trends (Hetherington, 2001).

29

30

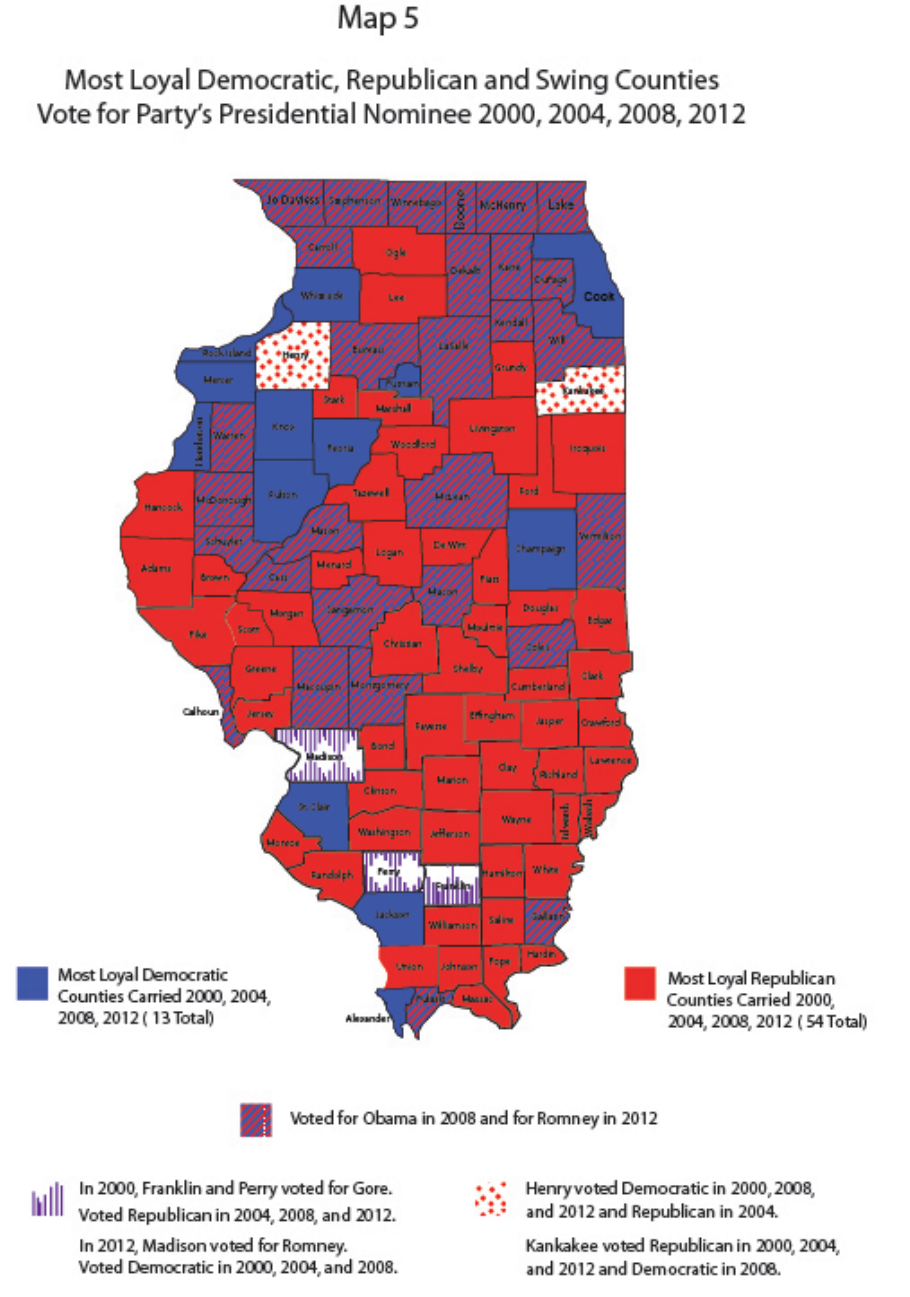

Map 5 extends the analysis back in time through the 2004 and 2000 presidential elections and

offers a comparison between those first two elections in the 21

st

century with the 2008 and

2012 results presented in Map 4. These longitudinal results provide a picture of mostly stability

at the county level; however, it also allows us to identify the most competitive counties where

change from election to election is evident and to note where perhaps more permanent

realignment could be taking place in these swing counties.

As is evident from Map 5 there are only 13 counties that consistently voted for the Democratic

candidate for president in all four elections between 2000 and 2012. Cook County, again, is by

far the biggest and most important of these loyal Democratic counties. Three of the deep blue

counties are in southern Illinois and the metro East area and the rest are in northwestern

Illinois, near the Iowa border and notably also include Champaign County in central Illinois, the

home of the state’s largest public university. There are 54 counties which have voted

consistently for the Republicans extending from George W. Bush in 2000 through Mitt Romney

in 2012. These counties extend across much of central Illinois, much of southeastern and

southwestern Illinois and to deep southern Illinois, and included an island of Ogle and Lee

Counties in far northern Illinois. In addition, the swing counties, which were mostly Republican

except for the Obama aberration in 2008, were mostly concentrated in northern and central

Illinois.

This is by far the larger geographic region of the state taken as a whole and would appear to be

a problem for the Democrats if one takes the county level and its importance for party building

seriously, as I do. In addition, these counties constitute the most fertile ground for electing

state legislators. These are the counties where you frequently find the Republicans controlling

the State Senate and State House seats for generations no matter who they run. However, on

statewide election returns, as we have already seen above, the prospects for the Republicans

are not so promising. The loyal Democratic Counties include Cook and some of the other

bigger counties with a total population of 6,246,565. Even without Cook County, the loyal

Democratic Counties have a total population of 1,051,890. See Appendix E.

The 54 consistently loyal Republican counties include most of the smaller counties in Illinois as

well as a few medium sized ones; however, Tazwell (Pekin) is the only county over 100,000 in

population in the group. The next largest are Adams (Quincy) and Williamson (Marion) at 67

and 66 thousand respectively. The total population of the loyal Republican counties comes to

1,318,134. See Appendix F. Thus, the population differentials leave the Democrats in a clearly

advantageous position among the most loyal counties when the statewide election returns are

counted. When one examines the most competitive or the “swing counties” which include all

the Collar Counties, that is where the great majority of the state’s population, outside Cook

County lives, as we have already stressed in the earlier population data. While the Collar

31

Counties have been very Republican historically, they are becoming more diverse and

sometimes provide a majority vote for statewide Democratic candidates or help swing the

election for them. Again the real balance of power now resides in suburban Cook and the

Collar Counties as noted earlier.

There was one additional county, Madison, where the Democrats won the first three

presidential elections of this century; however, it changed from Obama in 2008 to Romney in

2012. It is the only county in the state with this particular record. Madison County is a county

in the Metro-East area and has been growing as something of a bedroom community for St.

Louis and St. Louis County which is just across the Mississippi River, and it has become an

“exurban” county for metropolitan St. Louis. Perhaps not surprisingly it resembles other outer

ring suburban counties in its movement toward the Republicans and away from Obama in 2012.

The other two deviant cases are Franklin and Perry County in deep southern Illinois. They both

voted for Al Gore in 2000, and then that was the end of their loyalty to the national Democrats.

These two counties were formerly strongholds of the Democratic Party and had been a part of

the southern Illinois bedrock for the Democrats virtually since the Civil War. However, as was

explored above, parts of southern Illinois are in a realigning process which will be explored in

more detail in the next section of this paper. These two counties still have some Democrats left

at the Court House; however, they have not voted for the party’s national standard bearer since

Al Gore ran in 2000 and they did not vote for the Democrat for Governor in 2010. This is very

similar to what has happened in the southern states which make up the Old Confederacy.

Implications for Realignment

The New Deal Coalition which originally was glued together by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

in the wake of the Great Depression dominated American politics from the 1930s easily into the

1960s, and arguably there were echoes of it being still intact and supporting the election of

Jimmy Carter in 1976. However, the old New Deal Coalition was inherently unstable. It

contained almost equal parts of the liberal base in the Northeastern, Midwestern and Western

cities aligned with the most conservative elements in the nation found in the South, and

especially in the rural South. It contained union members and union bosses who had to live

with and a find modus vivendi with what V. O. Key called “the big mules” of southern politics,

the planters, business owners and extractive industries owners and operators who were

virulently anti-union and pro Right-to-Work laws (Key, 1949).

Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s this coalition contained the inchoate and increasingly

assertive civil rights movement, originally grounded in the black churches and in such liberal

unions as the United Auto Workers, the United Mine Workers, the Laborers, and the

32

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. These unions and the civil rights leaders increasingly faced

off against the most segregationist public officials, especially the southern Governors like Orval

Faubus, Ross Barnett, Lester Maddox, and especially George Wallace who were both racists and

vehemently opposed to unions and protective of their state’s Right-to-Work laws all of which

constituted a coherent public policy package for these governors and their allies in the state

legislatures.

These were inherent contradictions in Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition which could no longer be

papered over and contained. As the civil right leaders and their foot soldiers in the field

demonstrated, marched and attacked the very structure of state supported segregation, the

walls of American apartheid began to give way and later fell. Along with that fall, the New Deal

Coalition crumbled and had to be reassembled with different components, and the whole

American party structure went through a fundamental transition that culminated in the

partisan realignment and the deep partisan polarization that undergirds all of American politics,

and especially American presidential and congressional politics in the second decade of the 21

st

Century.

The Obama Coalition (or it could be termed the “Clinton-Obama” coalition since it started with

Bill Clinton’s presidency) has some of the key elements of the old Roosevelt Coalition, i.e. a

base in the cities and the unions, the “symbol specialists” who work in the media and the

creative arts, and many upper-middle and upper-class people who work in knowledge based

jobs in what Judis and Teixeria call the “ideopolis” (Judis and Teixeria, 2002). In their

provocative book, The Emerging Democratic Majority, published just over a decade ago Judis

and Teixeira applied their concept to Illinois in the following geographic terms:

Across the entire state, the Democrats’ gains in Illinois are almost exclusively in the

state’s ideopolises….Fortunately for the Democrats, the state’s growth has been

concentrated in the ideopolis counties. The greatest increases in population during the

1990s came (in this order) in the four ideopolis counties of Cook, DuPage, Lake, and Will.

If this continues, the Democrats’ hold over bellwether Illinois looks secure for the early

twenty-first century (Judis and Teixeria, 2002, 103).

The demographic and political developments in Illinois during the first twelve years of the 21

st

Century clearly support their thesis. The two presidential victories for Obama in 2008 and 2012

also seem to support their predictions for national politics. Only the continued Republican

control of the U. S. House of Representatives points in the opposite direction. The House is

particularly defined by the distribution of the population, and gives a structural edge to the

Republicans which coupled with the Republican victories in the state legislatures in 2010 gave

them a real advantage in the redistricting process attendant the 2010 Census.

33

This advantage, in turn, helped the Republicans continue their control of a majority of the

House in 2012 in spite of it being a very good year for the Democrats overall and a year in which

they won more popular votes in total than the Republicans did. It also should be noted that

the Democrats gained a net of four new House seats in Illinois in the 2012 elections, and this

resulted from the advantage the Illinois Democrats enjoyed in 2011 of controlling the

redistricting process just as the Republicans did in some thirty of the other states. So, in this

sense, the Democrats in Illinois were isolated from the national trends by their locally and

geographically based strength in the state’s General Assembly which translated into a marked

Democratic advantage in the Illinois House delegation.

So, in 2012 the Democrats and Barack Obama prospered nationally and nowhere was that

prosperity more evident than in Obama’s home state of Illinois. Obama put together a national

coalition which carried him to a resounding electoral victory in 2008 which was then reaffirmed

with his re-election, albeit by a narrower margin, in 2012. In the wake of the 2012 results

which were so disappointing from a Republican perspective, there was much soul-searching

and much analysis devoted to trying to redirect the party’s future and map a path back to a

more competitive electoral strategy. The Democrats were making their own long term strategic

plans, and a part of it had to be based in geography and driven by changing demographics

(Rothenberg, 2012).

In national terms the Clinton-Obama Coalition has lost a key element of the old Roosevelt