University of Birmingham

Sport policy in China (Mainland)

Zheng, Jinming; Chen, Shushu; Tan, Tien-Chin ; Lau, Patrick Wing Chung

DOI:

10.1080/19406940.2017.1413585

License:

None: All rights reserved

Document Version

Peer reviewed version

Citation for published version (Harvard):

Zheng, J, Chen, S, Tan, T-C & Lau, PWC 2018, 'Sport policy in China (Mainland)', International Journal of Sport

Policy and Politics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 469-491. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1413585

Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal

Publisher Rights Statement:

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics on 15th May

2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/19406940.2017.1413585

General rights

Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the

copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes

permitted by law.

•Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication.

•Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private

study or non-commercial research.

•User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?)

•Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain.

Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document.

When citing, please reference the published version.

Take down policy

While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been

uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive.

If you believe that this is the case for this document, please contact [email protected] providing details and we will remove access to

the work immediately and investigate.

Download date: 31. Aug. 2024

1

Sport policy in China (Mainland)

Jinming Zheng (Corresponding author)

Hong Kong Baptist University

Email: [email protected]

Shushu Chen

University of Birmingham

Email: [email protected]

Tien-Chin Tan

National Taiwan Normal University

Email: [email protected]

Patrick Wing Chung Lau

Hong Kong Baptist University

Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author: Jinming Zheng. Email: [email protected]

2

Sport policy in China (Mainland)

Abstract

Sport has been an integral part of the Chinese government’s policy agenda since the People’s

Republic of China (PRC) was founded in 1949. The policy prominence of sport has been further

elevated in the last two to three decades, as indicated by the steady increase in elite sport success,

the hosting of sports events such as the Olympic Games, China’s increased global engagement

with sport organisations and the developments in sport professionalisation and commercialisation.

This article reviews China’s sport policy at different periods since its inception, analyses the

rationale for, and form and extent of, government intervention, presents the sport structure in

China and identifies the dominant characteristics of its sport policy. In addition, various sport

policy areas, ranging from elite sport and mass sport, to sports mega-events, and sports

professionalisation are discussed, and their relative policy significances are compared. The

degree of balance between these areas and policy priorities are thus defined. Finally, emerging

trends and issues are introduced.

Keywords: China; sport policy; elite sport; sport for all; GAS

3

Introduction

Sport has a long history in China. Traditional sports such as dragon boat racing, cuju (the ancient

football) and martial arts have been rooted in China for more than a thousand years. However,

China, which has long been influenced by neo-Confucianism and by an emphasis on intellectual

activities (Xu, 2008), did not have a strong sporting culture before the 20th century. Only

following the establishment of People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 did sport become an

important policy area. In brief, China’s sport system ‘began in the 1950s, developed in the 1960s

and 1970s and matured with its own character in the 1980s’ (Hong 2008, p. 27).

Politicisation is a dominant characteristic of sport development in China (Zheng 2015). In

recent years, various aspects of sport, including elite sport, mass sport, sports professionalisation,

and the hosting of sports mega-events (SMEs) have developed rapidly, and sport has become a

prominent industry in the country. This has enabled sport to receive an increasingly significant

status within the government. A wide range of sports policy documents and laws have been

formulated and implemented, including the Sports Law, three versions of Strategic Olympic

Glory Plan, several editions of the Five-Year Plan for Sport Development in China and the

National Fitness Programme (GAS, 2002, 2006, 2011a, 2011b, 2016, Sports Commission of

China 1995, The State Council of the People's Republic of China 2014, 2016).

This paper, as a panoramic country profile in nature, reviews sport policy development in

all prominent areas in China and aims to present the basic sports landscape and introduce the

fundamental sport policies of various sport areas to an international audience. These include elite

sport, mass sport, sport professionalisation and the hosting of SMEs. It is noteworthy that the

discussion of elite sport is the most detailed because of the Chinese government’s longstanding

prioritisation of elite sport success. However, other areas are also reviewed, particularly China’s

4

policy development in relation to mass sport, professionalisation and the hosting of SMEs over

the last two to three decades. The value of this research resides in its (1) comprehensive

presentation of the sport scene in China; and (2) timely coverage of and reflection on the latest

developments in various aspects of sport in China, which are not reflected in the vast of majority

of existing studies on sport in China. In specific terms, this articles aims to (1) summarise

government involvement in sport in China at different periods with primacy given to the last

three to four decades (i.e. since the 1980s); (2) introduce the organisational structure and analyse

the role of government within China’s elite sport system; (3) identify the sources of funding and

the trends with a focus on elite sport; (4) explore policy and strategic factors underpinning

China’s notable elite sport success, one of the most dominant characteristics and overriding

government priorities; and (5) discuss the emerging trends and key contemporary issues in elite

sport, mass sport, sport professionalisation and the hosting of SMEs.

This article is structured into eight sections. The next section critically reviews existing

literature on sport policy in China. The next section is concerned with the trajectory of sport

policy development in China, and government involvement at different periods. This is followed

by a summary of the organisational structure of sport in China, after which the funding sources,

figures and trends are introduced. A separate section on elite sport in China is provided, because

of the distinctive politicised sport system of China where elite sport has long been the most

salient policy area, despite recent developments in other sports areas such as mass sport and

sports professionalisation. The penultimate section discusses the new trends in Chinese sport.

The article ends with a brief conclusion, which summarises the key findings of the analysis.

5

Literature review: sport in China

Research on various aspects of sport in China has burgeoned in English literature in the last two

decades. Fan Hong and her colleagues (for example, Hong 1998, 2008, 2011, Hong and Lu

2012a, Hong, Wu and Xiong 2005) introduced the history of various aspects, most notably elite

sport and mass sport in China at different periods since 1949. The political, economic and

cultural contexts, political rationale, and significance of sport throughout the PRC period are

analysed in depth in their works, which enables a basic understanding of the sport scene in this

nation. Susan Brownell and Jinxia Dong also published a number of studies on sport, including

the political and non-political utility of sport in China, women and sport and the development of

the sport policy agenda from historical and sociological perspectives (Brownell 2005, Cao and

Brownell 1996, Dong 1998, Dong and Mangan 2008).

Xu (2008) summarises sport history in the PRC, from its origins to Beijing 2008,

including a discussion of important political events that involved sport such as the tension

between the PRC and Taiwan, and the Ping-Pong diplomacy between the USA and PRC. In

addition, Xu (2008) explored the politics of the growing significance of elite sport success and of

the hosting of the Olympic Games. This book provides very insightful understanding of the sport

development in China and its politicisation, with considerable historic detail presented and

analysed. However, mass sport was not included, and the book’s historical nature implied a lack

of policy analysis.

More recently, Jinming Zheng and Xiaoqian Hu’s works have contributed to the existing

literature on sport in China. For example, Zheng and Chen (2016) explored China’s strategic

approaches to elite sport success and sport categorisation and prioritisation, Zheng (2016, in

press) and Zheng, Tan and Bairner (2017) examined the detailed development and policy

6

approaches in three sports/disciplines in China: cycling, swimming and artistic gymnastics. Hu

and Henry (2016) focused on the development of Chinese elite sport discourse in the lead-up to

and in the aftermath of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, while Hu and Henry (2017) applied

discourse analysis to investigate the reform and maintenance of Juguo Tizhi (the whole country

support for the elite sport system), a fundamental underpinning of China’s significant elite sport

success.

Tien-Chin Tan and his colleagues have advanced research on sport in China through case

studies of several sports (for example, basketball, football and table tennis, Chen, Tan and Lee,

2015, Houlihan, Tan and Green, 2010, Tan and Bairner, 2010, 2011, Tan and Houlihan, 2012)

from the distinctive perspectives of globalisation and the professionalisation of sport in China.

Regarding sport for all, X. Chen and S. Chen’s (2016) work provides an analysis of youth sport

in China and considers the role played by the state in its development.

Despite the significant contributions of these scholars, there remains a dearth of research

systematically examining the rich tapestry of sport policy in the People’s Republic of China that

encompasses a discussion of elite sport, mass sport, major sports events, professional sport and

their relative significance and interaction within the entire realm of sport in China. In addition, as

noted above, China’s most recent developments and trends in various sport policy areas have not

been fully discussed. This research fills this gap through its comprehensiveness and timeliness.

A history of government involvement in sport and rationale

This section reviews sport policy development and government involvement in sport at different

periods since the establishment of the PRC in 1949. Discussion is further divided into five

sections, echoing four critical junctures either in the history of China in general or in Chinese

7

sport history in particular: the eruption of the Cultural Revolution in 1966; the end of the

Cultural Revolution in 1976; China’s poor performance at the Seoul 1988 Olympic Games; and

Beijing’s success in bidding to host the 2008 Olympic Games in 2001. The rationale behind such

periodisation is that the 1950s and early 1960s witnessed the establishment of a government-led

sport system, and the early development of elite sport and mass sport, while sport was largely

paralysed during the ten-year turbulence of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The end of the

Cultural Revolution, and the subsequent economic reform and opening up policy raised the

salience of sport and particularly prompted China’s rapid progress in elite sport. However,

China’s poor performance at the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games (five gold medals vs. 15 gold

medals at Los Angeles 1984) was a turning point, as well as a wake-up call propelling large-

scale reform in elite sport development, which was a key priority in China. The significance of

Beijing’s successful bid in 2001 transcends sport. It was a key political event in China, and gave

elite sport, as well as other aspects of sport in China a new prominence. It is noteworthy that this

periodisation is elite sport-centred, but despite the Seoul 1988 the impact of which was more

specific to elite sport, all the other junctures also had a marked impact on the entire sport scene

in China.

1949-1966

On October 1 1949, the PRC was established. As a consequence of the government’s concern for

the health of the nation, national representation, nationalism and identity, international prestige

and the superiority of Communism (Hong 1998, 2008, Xu 2008), sport became an important

government consideration. There were dual priorities in the development of sport in the 1950s:

mass sport and elite sport. The significance of mass sport was demonstrated in the landmark

8

slogan by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1952: ’Develop physical culture and sports, strengthen the

people’s physiques (fazhan tiyu yundong zengqiang renmin tizhi)’ (Dai, Shao and Bao 2011, p.

107). In the 1950s, six institutes and eleven schools of physical culture were established and 38

high-level normal colleges reopened their Physical Education departments. Following the lead of

the Soviet Union sport was not only a vehicle for improving health but also served national

defence (laoweizhi).

Concerning elite sport, the Sovietisation of sport was a key feature in the 1950s (Jarvie,

Hwang and Brennan 2008). The PRC’s debut at the Helsinki Olympic Games in 1952

demonstrated the potential of sport as an effective vehicle serving the political and diplomatic

purposes of the government (Hong and Lu 2012a). Against this backdrop, the State Sports

Commission (hereafter the Sports Commission) was created by the Government Administrative

Council in November 1952, which became responsible for sport-related issues in China. Vice-

Premier He Long was appointed chairman of the Sports Commission. Following He Long’s

instructions, a complete top-down organisational system was soon established nationwide, with

each province, municipality, and autonomous regions creating their own sports commissions in

the ‘relevant bureaus of the Ministry of education, the Central Youth League, and the General

Political department of the Military Commission’ (Cao and Brownell 1996, p. 70). In 1956, The

Elite Sport System of the PRC was officially launched by the Sports Commission. It was a

landmark document that laid the foundations for the elite sport system in China (Hong and Lu

2012a). According to the document, 43 elite sports were recognised, rules and regulations were

formulated, full-time sports teams were organised at both national and provincial levels and

sufficient competition opportunities were provided. In the same year, the Sports Commission

issued The Regulations for Youth Extra-Curricular Sports Schools. In so doing, the Soviet

9

Union’s extra-curricular sports school model was adopted and disseminated in China. Extra-

curricular sports schools still play an essential role in China’s sporting success on the

international stage, acting as the first rung on the talent development ladder. It is noteworthy that

this Sovietised system provided men and women with equal sports opportunities, which

propelled the later success of Chinese sportswomen (Brownell 2005).

The time between 1958 and 1966 was characterised by Cao and Brownell (1996, p. 71) as

a period of ‘political upheavals’ (the anti-rightist movement and ‘the Great Leap Forward’, GLF,

dayuejin) and ‘economic difficulties’ (the Three Hard Years, sannian ziran zaihai, as a

consequence of both the deterioration in the Sino-Soviet relations and natural calamities from

1959 to 1961). Mass sport suffered greatly during this series of political movements, first

because of unrealistic and ‘premature’ (Cao & Brownell 1996, p. 72) policies and ambitions in

the GLF during which enormous resources were wasted, and then during the three-year period of

famine and economic difficulties. In contrast, elite sport was arguably a beneficiary. The

previous policies of ‘preparing for labour and defence’ and ‘to popularise and to practice

regularly’ were replaced with a new policy in 1959 designed ‘to popularise and to improve’,

which stressed the significance of improving the level of elite sport (Lin 2006). In 1959, the First

National Games was held in Beijing. Different from mass sport, elite sport served the

government’s slogan of catching up with and overtaking leading nations and hence its

development was accelerated.

In 1963, another key policy document Regulations for Outstanding Athletes and Teams,

was issued by the Sports Commission. According to the regulations, each province was required

to establish a youth talent search and identification system to support elite development. In

addition, ten

1

out of the previous 43 sports were selected as the priority sports, in which the

10

government invested heavily for future success on the global stage. From that time, Chinese

sport started to shift from ‘two legs’ (mass sport and elite sport) to ‘one leg’ (elite sport

prioritised) (Hong 2011). In brief, the period 1961-1966 was the consolidation of the elite sport

system in China.

1966-1976

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a special and turbulent time in China, during which

sport was paralysed and largely demolished (Jarvie, Hwang and Brennan 2008). As Johnson

(1973, p. 93) characterised, ‘the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s smashed across China like

a violent sandstorm’. In so doing, Mao Zedong’s unparalleled authority was established. During

the Cultural Revolution, the people (workers and peasants) and collectivism were highly valued,

while the elite group, ranging from science to sport, was severely criticised and often physically

threatened or assaulted. In 1968, the ‘May 12th Order’ suspended almost every sports activity in

China (Dai, Shao and Bao 2011). The head of the Sports Commission, Marshal He Long was

severely criticised and beaten by the Red Guards and finally died in prison in 1969. In the first

half of the Cultural Revolution the elite sport system was devastated. According to Hong (2008,

p. 30), ‘the training system broke down, sports schools closed, sports competitions vanished, and

the Chinese teams stopped touring abroad’. Mass sport was also undermined by the ceaseless and

widespread violence. Schools were closed and teachers were persecuted. However, there were

several developments from 1971 onwards. ‘Ping-pong diplomacy’ with the USA and frequent

sporting communication with China’s ‘Third World’ friends were the most noteworthy

developments (Xu 2008, p. 117). As Wu (1999) outlined, Chinese government realised the

11

inseparable relation between sport and politics and athletes acted as sports ambassadors, which

conferred new diplomatic utility on sport.

1976-1988

A new era dawned for sport in China with the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 with elite

sport emerging as the overriding priority. As Wu (1999) pointed out, to raise the national flag of

China at the Olympic Games became an important government responsibility. What underpinned

China’s unprecedented sporting success were the ‘whole country support for the elite sport

system’ and the Olympic Strategy. By contrast, mass participation was required to take a back

seat. From the origins of sports reform in 1979, China’s sports development pivoted on the

principle of ‘prioritising elite sport, then leading subsequent general development’ (Wu 1999).

The profound changes regarding the political backdrop in the late 1970s, including the

end of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping’s taking office and the adoption of large-scale

domestic reform and the ‘open-door policy’ had a marked and irreversible impact on sport. Since

the 1980s, as the Chinese have become more self-confident, ‘nothing better symbolises the drive

to achieve greater prestige than sports’ (Xu 2008, p. 207).

In late 1979, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) passed the Nagoya Resolution

and the PRC’s seat in the IOC was reinstated after a 21-year absence (Jarvie, Hwang and

Brennan 2008). ‘Develop elite sport and make China a superpower in the world’ became a

slogan and pursuit for the Chinese (Hong 2008). Elite sport received a salient profile inside the

planned economy and administrative system and the government decided to concentrate its

limited resources on the medal-winning sports (Rong 1987).

12

Immediately in the wake of the success at Los Angeles 1984, the Central Committee of

the Party issued the Notifications Regarding the Further Development of Sport, the main theme

of which was ‘to better arrange the strategic distribution, to concentrate on the sports in which

China had advantages, and to enhance weak sports such as athletics and swimming’ (GAS 2009,

p. 35). The landmark Olympic Strategy was issued in 1985. In this document, elite sport was

established as the priority both in the short term and long term.

In 1986, the Sports Commission issued the Decisions about the Reform of the Sports

System (Draft), further emphasising and confirming the Olympic Strategy and the significance of

elite sport in relation to the modernisation of China in the 20th century.

1988-2001

China’s poor performance at the Seoul 1988 Olympic Games was a ‘wake-up call’ prompting a

succession of government actions designed to enhance China’s competitiveness on the Olympic

stage. First, at the end of 1988, Wu Shaozu was appointed as the new head of the Sports

Commission. China established and consolidated its position as a member of the leading group

on the Olympic stage during Wu Shaozu’s twelve-year tenure (1988-2000). Second, the

government raised the sports budget by a big margin. It was revealed by Xu (2008) that the total

sports budget covering the Seoul Olympiad was four billion yuan (Chinese currency unit) (one

billion yuan per year) while the budget surged to three billion yuan per year in the Barcelona

Olympiad (twelve billion yuan in total). Third, the disappointing experience in Seoul urged

China to pay more attention to the elite sport development systems of its major rivals. A national

symposium was held in 1989, involving detailed analysis of the top three sports nations (Soviet

Union, the USA and East Germany) and two major Asian rivals (Japan and South Korea).

13

Furthermore, China started to realise the significance of, and hence place serious emphasis on,

science in sporting success (ifeng 2009).

In 1992, the government decided to officially adopt a market economy in the 14th

National Communist Party Congress. This decision has left an indelible imprint on Chinese sport,

with major sports such as football, basketball and table tennis becoming professionalised and

commercialised in ensuing years. However, it was very difficult for most other sports to become

financially self-sufficient.

China’s recovery at Barcelona 1992 (16 gold medals vs. five at Seoul 1988) reinforced

the government’s commitment to elite sport success. In 1993, the National Games was

rescheduled to the year after the Summer Olympic Games in order to better serve Olympic

preparations. Furthermore, the National Games started to be integrated into the preparations for

the Olympic Games, copying the Olympic sports setting and including all Summer Olympic

sports and events. The National Games has since become a development event, or ‘training

ground’ (Hong 2008, p. 42) for the Olympic Games. It is also used as a platform for the selection

of talented athletes and coaches.

1995 was a milestone in Chinese sports history. Within one year, three landmark sports

documents were published. First, in the 1990s, the pressure of ‘rising demands of grass-roots

sports participation’ (Hong, Wu and Xiong 2005, p. 514) resulted in the issue of the National

Fitness Programme by the government, aiming to promoting people’s sports participation and

strengthening people’s physical health (GAS, 2009b). As the General Administration of Sport of

China (GAS 2009b) noted, the publication of the National Fitness Programme raised mass sport

to a new level in China. The conception of the National Fitness Programme, in combination with

the accompanying legislation, signalled the sport-for-all agenda’s active role in policymaking;

14

however, sport for all was still deemed a lower priority than was the agenda of elite sport

development. In relation to elite sport, the first Outline of the Strategic Olympic Glory Plan:

1994-2000 was published by the Sports Commission (Sports Commission of China 1995). This

heightened the salience of Olympic success within the government. Last, China’s first sports-

related law – Sports Law of People’s Republic of China was passed by the government on

August 29 and came into effect on October 1.

After China’s gold medal success at Sydney 2000, the term Juguo Tizhi (Liang, Bao and

Zhang, 2006) began to be frequently referred to as the key contributory factor of China’s rise

since 2000, the significance of which was recognised by the then Chairman Jiang Zemin (Li

2000). The definition of the concept can be summarised as ‘the government, both central and

local governments, ought to efficiently channel the limited resources, including financial,

scientific, human and so forth to fully support elite sport development and Olympic success, in

order to win glory for the nation’ (Yuan 2001, p. 364).

Equally important was the Chinese government’s effort in hosting SMEs. The rationale

was that ‘hosting the Olympic Games was an important part of the Olympic strategy to make

China a sports superpower, as well as a political and economic power, that could compete on

equal grounds with the USA, Japan and South Korea’ (Hong and Lu 2012c p. 145). The

unsuccessful experience in the 1993 Olympic Bid did not discourage Beijing and finally Beijing

won the right to host the 2008 Olympic Games in 2001.

2001-2016

After Beijing was elected the host city of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, the Olympics

became the focal point within the realm of sport in China and to some extent, one of the

15

paramount policy concerns for the Chinese government. Later in the same year of 2001, China

officially entered the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which has, inevitably, accelerated

China’s pace of globalisation (Chow 2001).

Since the 21

st

century, sport, in particular elite sport success, has gained more diplomatic

legitimacy because it provided the government with a great platform to showcase its soft power

and ideological superiority (Jarvie, Hwang and Brennan 2008). Economic growth has also

benefited elite sport development by providing Olympic sports with increased finance (see Table

3 and Table 4 for funding trends).

In July 2002, the government issued the policy document Further Strengthening and

Progressing Sport in the New Era, which stressed the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games as the

paramount priority for the whole country (GAS 2009b). Accordingly, GAS issued two internal

documents: The Outline of the Strategic Olympic Glory Plan: 2001-2010, and The 2008 Olympic

Glory Action Plan, the dominant features of both were the emphasis placed on Olympic medal

success (GAS 2002, 2003). As Lombardi (2008, quoted in Xu 2008, p. 225) argued, ‘winning is

not everything; it is the only thing’.

Athens 2004 was a rehearsal for China’s preparation for the 2008 Olympic Games. In

Athens, China’s performance ‘stole the limelight’ (Hong, Wu and Xiong 2005, p. 510). China

finally dominated in the gold medal table in Beijing 2008, confirming its status as a sports

superpower. The system of Juguo Tizhi did not fade away after the Beijing Olympics. The

significance of maintaining the system was stressed by Liu Peng, the head of the GAS (Hu and

Henry 2016). Later at the National Sports Congress in 2009, this continuity was confirmed by

Chairman Hu Jintao (Hu 2015a). At London 2012 China defended and consolidated the

16

achievements gained in Athens and came second in the gold medal table, without the home

advantage.

There have been improvements regarding mass sport. In the 2000s, fresh concerns about

young persons’ health brought mass participation development into the limelight (X. Chen and S.

Chen 2016). In 2002, GAS issued Opinions on Accelerating the Development and Improvement

of Sports Work in the New Era. This publication reiterated that the development of sports should

serve the Chinese people and that the development of national fitness should be one of the top

sports priorities. In light of Beijing’s successful bid for the 2008 Olympic Games in 2008,

however, political attention and state financial investment were for the most part still

strategically focused on the development of elite sport. Except for some sporadically issued

policy statements relating to the agenda of sport-for-all development, the ideal of mass

participation received little more than lip service.

Sport for all gradually gathered momentum again in the aftermath of Beijing 2008. The

State Council made August 8th national ‘Sport-For-All Day’ (The State Council of the People’s

Republic of China 2009) and issued National Fitness Regulations in 2009 by Premier Wen

Jiabao (GAS 2009b). This regulation distinguished itself from the often vague and inadequately

implemented policy statements published previously and it clarified the responsibility of relevant

bodies in the national fitness system, formalised a systematic national fitness test programme,

and formally addressed issues in relation to sports facilities and sports-related businesses.

The political priority of sport further increased following the election of the pro-sport

President Xi Jinping in 2013. His explicit sports passion propelled further development of sport

in China led by increased government support (Hu 2015b). China’s increased support for and

reform of football, the continuing endeavour to host high-profile SMEs most notably the

17

successful bid for the 2022 Winter Olympic Games and intended bid for the FIFA Men’s World

Cup, and Chinese entrepreneurs’ international participation including the purchasing of

renowned European league clubs were facilitated by Xi Jinping government’s favourable policy

environment and the policy objective to transform China into a ‘world sports power’ (Tan,

Huang, Bairner and Chen 2016, p. 1449).

At the London 2012 Olympic Games, China cemented its second-place position in the

gold medal table. There soon began to be much more public debate on how elite sport’s interests

could be complemented with potential benefits of developing sport for all. With these issues in

mind, the agenda of developing sport for all was finally singled out as a state priority. During the

preparation of the bid for hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics, President Xi proposed the goal of

‘using the 2022 Games to get a population of 300 million in China involved in winter sports’

(People.cn 2015). This target for the 2022 Winter Olympic Games was ambitious; linking an

Olympic event with sport-for-all development had not been explicitly addressed when the 2008

Summer Olympic Games was hosted. A few months after President Xi’s remarks, a strategic

document entitled Opinions of the State Council on Accelerating the Development of Sports

Industry and Promoting Sports Consumption (The State Council of the People’s Republic of

China 2014) was published. This signalled a clear government desire for sport for all, urged by

growing concern about the deterioration of children’s physical fitness and about the steady

increase in overweight among the population. Two documents published in 2016 provided

evidence of discourses consistently elevating the policy prominence of sport for all: The National

Fitness Programme (2016–2020) (The State Council of the People's Republic of China 2016)

and the 13th Five-Year Plan for Sports Development in China (GAS 2016). Fitness was

18

identified by the Chinese government as an important vehicle in achieving the policy objective of

upgrading China from a ‘major sports country to a world sports power’ (Tan 2015, p. 1071).

However, the increased emphasis on mass sport was again subjected to review because of

China’s underperformance at Rio de Janeiro 2016. In particular, the fact that China was

overtaken by Great Britain in the gold medal table prompted some policy interventions by the

State Council and GAS. The quality of (gold) medals is valued and China expressed its explicit

ambition in gold medal-abundant foundation sports (athletics and all water sports) and collective

ball sports (GAS 2011a). Leadership change was an immediate antidote prescribed by GAS,

which replaced the head coaches of the national teams in China’s ‘fortress’ sports that

experienced a sharp gold medal decline at Rio 2016, including artistic gymnastics, shooting and

badminton. These dismissed coaches had steered their respective national teams for more than

ten, or even twenty years (ifeng 2017a). In addition, debate arose again over the relative

significance of mass sport and elite sport, and over the danger of emphasising mass sport but

undervaluing the impact of elite sport success.

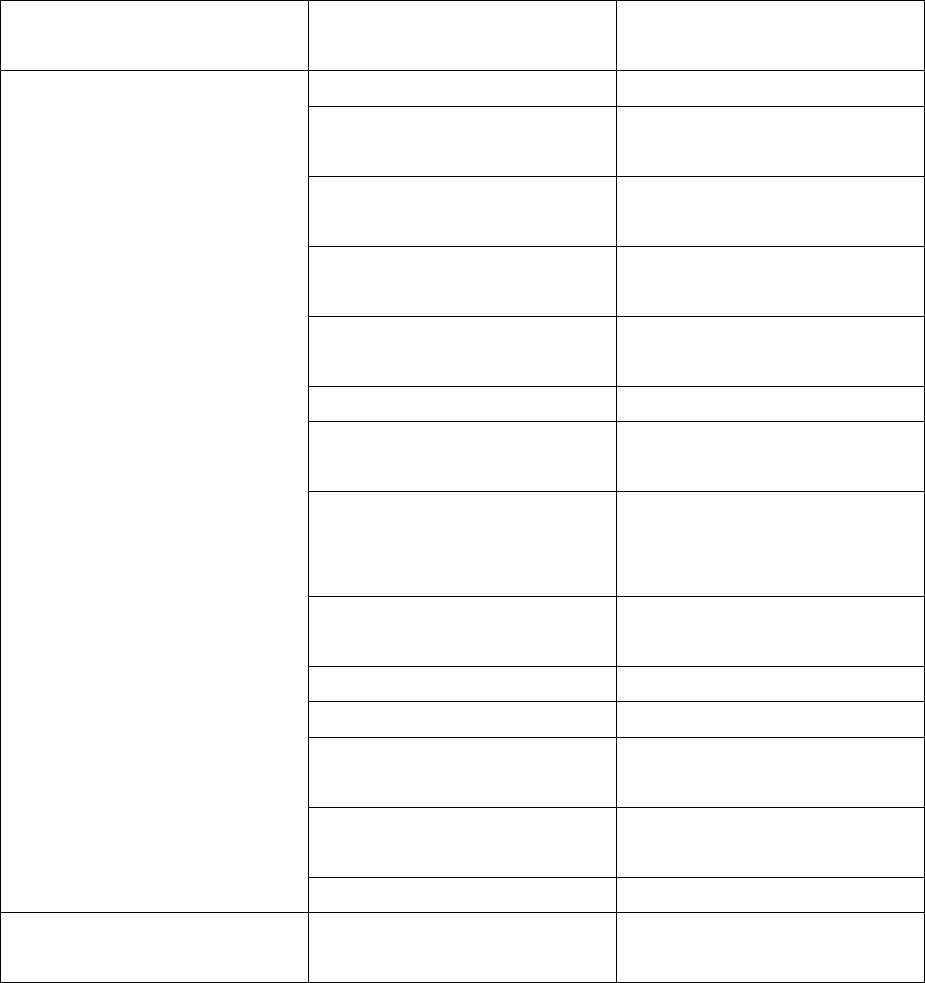

Organisational structure

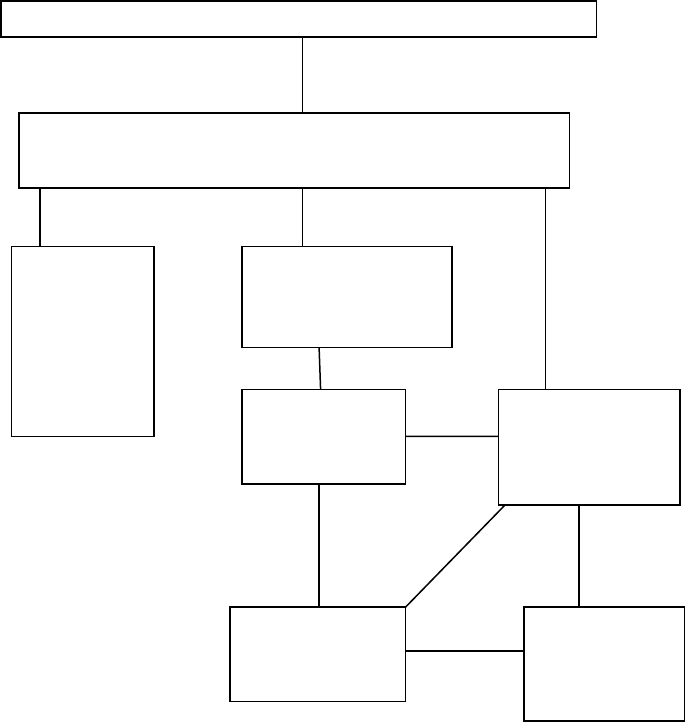

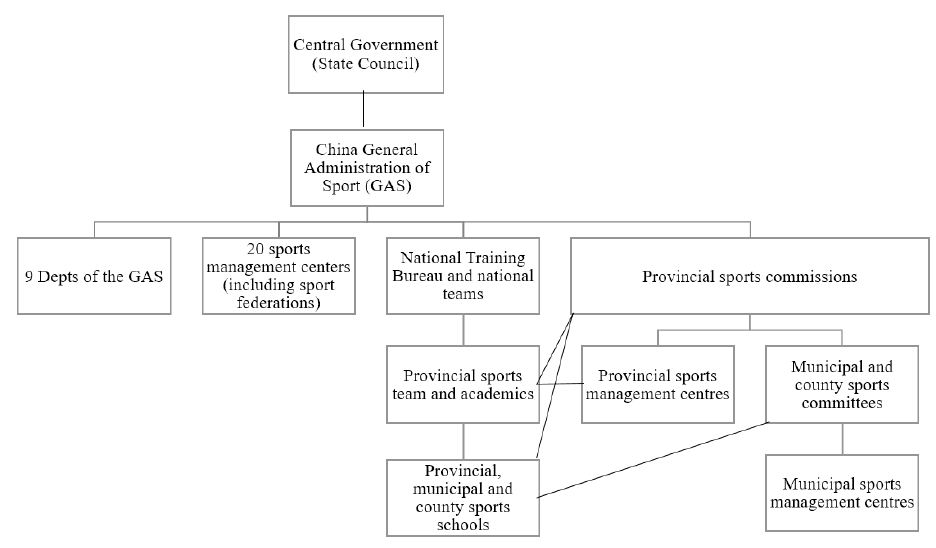

The most distinctive feature of China’s elite sport system is its centralised organisational

structure. As Hong, Wu and Xiong (2005, p. 514) argued, ‘the model of the Chinese sports

administrative system reflected the wider social system in China: both the Communist Party and

state administrations were organised in a vast hierarchy with power flowing down from the top’

(see Figure 1). This centralised model was largely the outcome of the transfer of the Soviet

model, most evident in the establishment of the Sports Commission the concept of which was

copied from the State Sports Commission in Soviet Union and the hierarchical structure from

central government to provincial, city and county levels (Dai 2009).

19

[Figure 1 near here]

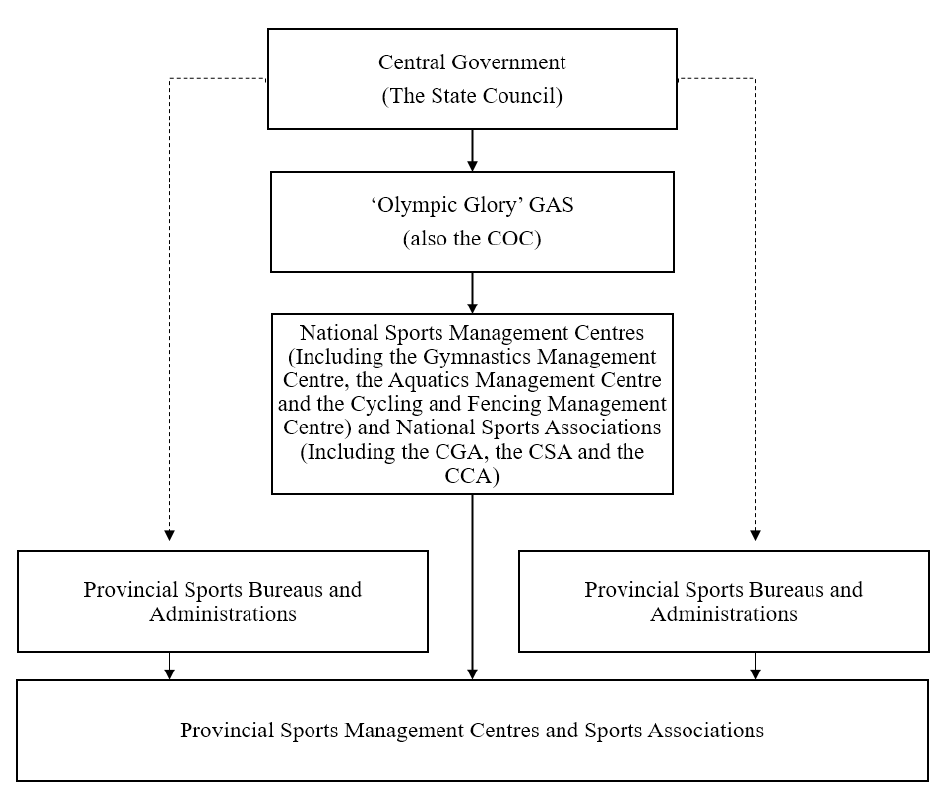

In 1998, the Sports Commission was renamed the General Administration of Sport of

China (GAS). The GAS was simplified, with the previous 20 departments merged into nine

departments. Although ostensibly this was a response to China’s ‘stagnant’ performance at

Atlanta 1996 compared to Barcelona 1992, this organisational reform needs to be understood

within the wider context of the restructure of government ministries of the Central Government

in the 1990s, following the simplification campaign and the objective of administrative

efficiency enhancement (Jizhong Wei, former Secretary General of the Chinese Olympic

Committee and the President of the Fédération Internationale de Volleyball, FIVB, 2017, quoted

in ifeng 2017b). Although the reorganisation blended some characteristics of market economy

and decentralisation, the aim was to establish a more efficient, cooperative and standardised

administrative system to serve the development of elite sport, as most evidently reflected in the

organisational specialisation on Olympic sports and disciplines (Pan 2012). Management centres

became the core governing bodies responsible for the development of each sport/discipline (Tan

and Green 2008). Figure 2 presents the reformed organisational structure, which is still in place.

[Figure 2 near here]

The basic administrative structure for elite sport remained stable during the period 2001-

2017. Currently, Olympic sports are governed by 14 Summer Olympic sport management centres

and one Winter Olympic sport management centre to which national sport associations (NSAs)

are affiliated (see Table 1). There is only a thin line between management centres and

20

associations, although associations are rhetorically defined as social organisations (Liu and

Zhang 2008). Most NSAs are nominal (Li 2008, p. 3). Li (2011) and Li and Zhou (2012, p. 31)

described this phenomenon as ‘the co-structure of management centres and associations’.

[Table 1 near here]

Provincial management centres that govern regional sport development are directly led

by their corresponding provincial sports bureaus or administrations (for example, Hubei

Administration of Sport 2013). Therefore, these management centres are the government units of

their province, municipality and autonomous region. Similar to the relationship between

provincial sports bureaus and GAS, provincial management centres are not directly governed by

the national management centre. The link between the national management centre and the

regional management centres is defined as a mentoring one (a previous department head of GAS

2013, quoted in Zheng 2015). Yet, in the cases of nationwide and Olympic-related issues,

regional management centres are expected to comply with the decisions and serve the needs of

their respective national management centre (see Figure 3).

[Figure 3 near here]

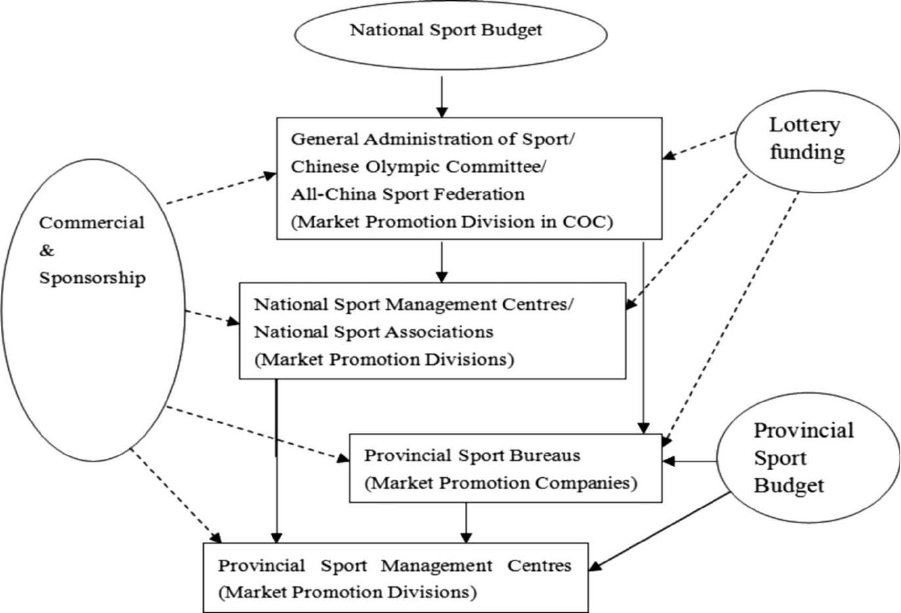

Funding

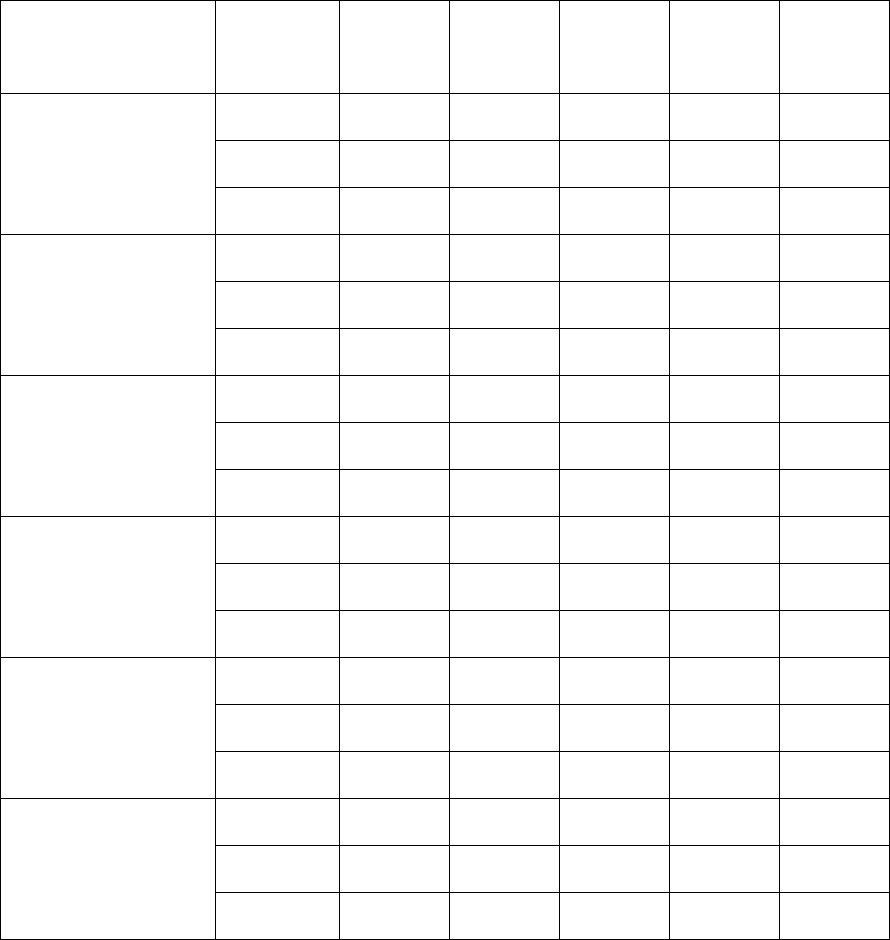

In China, the vast majority of the funds directed to sport are derived from the government budget.

This particularly applies to elite sport development in China. During the period 1976-1988, elite

sport relied overwhelmingly on central and local government sports budgets. The total amount of

21

money granted to sport during the period 1986-1990 doubled in comparison to that between

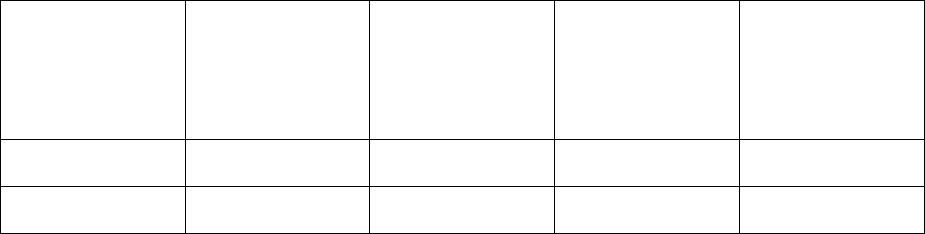

1981-1985 (see Table 2). It is noteworthy that 80% of the sports budget was distributed to elite

sport, as required by the Olympic Strategy (Hong 2008).

[Table 2 near here]

As noted above, there were drastic policy reforms in the aftermath of China’s poor

performance at Seoul 1988. An immediate response by the Chinese government was the dramatic

increase in sports budget. The total sports budget for the Barcelona Olympiad tripled in

comparison to that for the Seoul Olympiad (see Table 3). The annual figure increased by a larger

margin in the Sydney Olympiad and finally exceeded 10 billion yuan in 2001. The total amount

of sports funds for the Sydney Olympiad was almost twice as much as that for the Atlanta

Olympiad. Elite sport was the largest beneficiary. As Hong (2011, p. 406) observed, ‘the

proportion of the government’s sports budget spent on elite sport compared with mass sport

became extremely skewed’. In comparison, sports lottery was fairer and it was reported that the

vast majority of the lottery money was granted to mass sport.

[Table 3 near here]

Despite the hegemonic dominance of government subvention in funding sport

development, the source of financial support for sport in China has become more diverse in

recent years. In general, there are three main sources of sports funds: government sports budget,

commercial money and lottery funding (see Figure 4). The incorporation of commercial money

22

in supporting sport, including elite sport (through sponsoring the team or individual, mainly star

athletes) is a clear manifestation of the burgeoning developments of economics in general, and of

commercialisation and professionalisation in China since the 1990s. However, it is noteworthy

that private sectors, despite their substantial financial contributions, are strictly excluded from

decision making of GAS, and hence have very limited impact on the policy direction of sport

development in China (a senior policy maker and previous department head of GAS 2013,

quoted in Zheng 2015).

[Figure 4 near here]

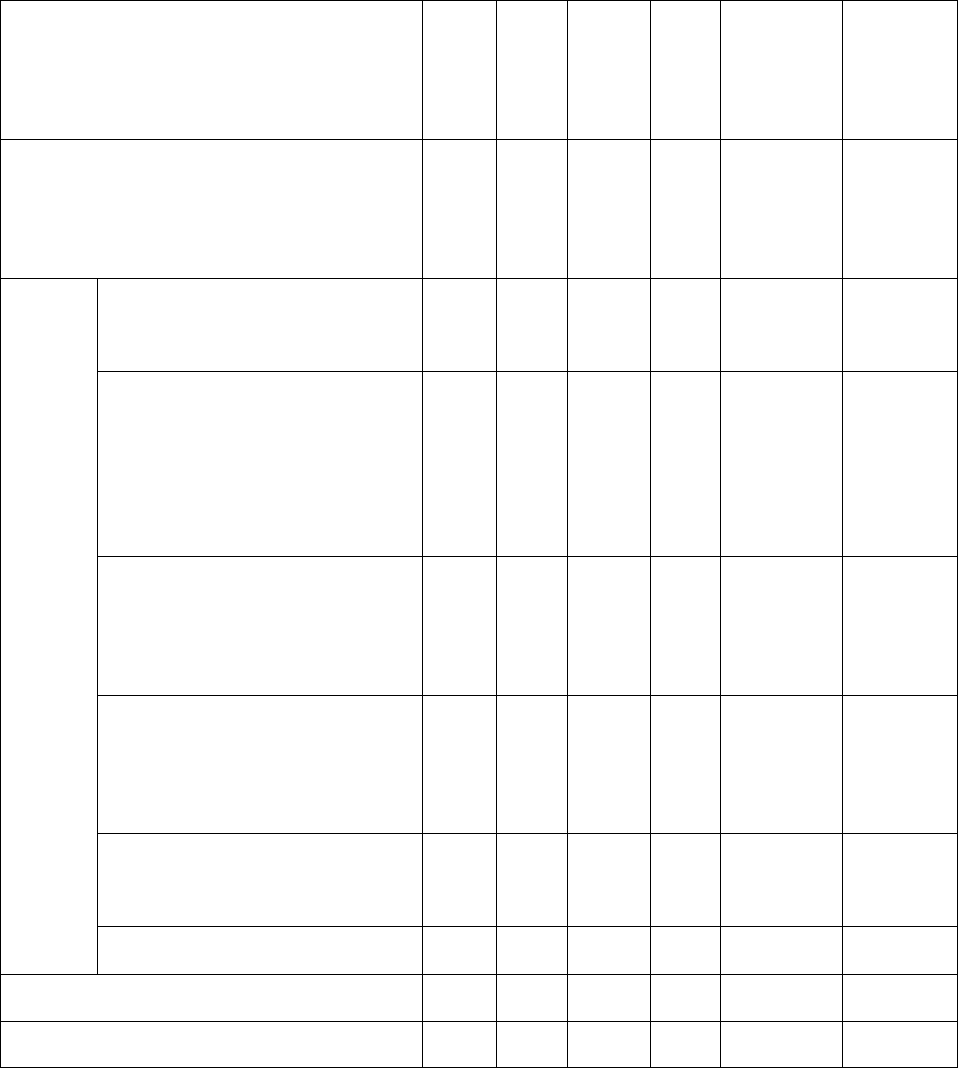

Table 4 shows the budget of GAS from 2007 to 2015, which focuses on funding at the

central government level. Data prior to 2007 are not accessible, while the figure for 2016 has not

been released at the time of writing.

[Table 4 near here]

Elite sport achievement, and underlying policies and strategies

There is little doubt that elite sport has been the most prominent sport policy area in China.

Despite the increased policy profile of mass sport in recent years, elite sport remains the

overriding priority within the Chinese government. Government involvement has been propelled

by a series of political, diplomatic, social and ideological purposes, which has been consistent in

securing the prominence of elite sport on Chinese government’s agenda almost since the

inception of the PRC.

23

China’s rise on the Olympic stage in particular its growth to be one of the most successful

Summer Olympic nations has been noticeable. Since China returned to the Summer Olympic

Games, Chinese athletes have won 227 gold medals at the Summer Olympic Games. In addition,

since the gold medal breakthrough at Salt Lake 2012, China has won 12 gold medals at the

Winter Olympic Games. This success has been fuelled by various deliberate and effective

policies and strategies. First, a wide range of ongoing fundamental policy documents have laid

the foundations for China’s elite sport success. As noted above, the issue of Olympic Strategy

was a landmark event in sport in China, which legitimised elite sport’s status as the policy

priority. After this, three versions of The Outline of the Strategic Olympic Glory Plan directed

elite sport development in each of the three decades between the 1990s and 2010s. According to

Zheng and Chen (2016, p. 164), China’s underlying philosophy has evolved from ‘shortening the

battle line and emphasise the focus’ prior to the 2000s, to ‘seeking new sources of Olympic gold

medals’ in the 2000s and ‘raising the quality and value of Olympic gold medals’ after Beijing

2008 which targets the quality of medals and the success in more internationally popular

sports/disciplines.

In addition to these fundamental policy documents, there were a series of specific policy

documents published and measures adopted at various critical junctures. Beijing’s successful

Olympic bid further accelerated elite sport development in China, which eventually paved the

way for China’s top position in the gold medal table. In addition to The Outline of the Strategic

Olympic Glory Plan: 2001-2010, a Beijing 2008-specific elite sport policy document The 2008

Olympic Glory Action Plan (GAS 2003) was issued to further emphasise China’s quest for the

maximisation of success on home soil as a paramount policy objective. Furthermore, two

landmark projects were launched, namely 119 Project (GAS restricted internal document), and

24

Preliminary recruitment of foreign coaches and organisation of overseas training: The inception

of the ‘Invite In and Go Out’ (GAS restricted internal document). All these policy initiatives

lifted elite sport development to a new high in China.

While various policies have made substantial contributions to China’s elite sport

achievements, the role of China’s longstanding deliberate and strategic planning is also

noteworthy. To avoid the misuse of money, increase funding efficiency and maximise China’s

Olympic (gold) medal prospect, China has prioritised primarily skill-based, and ‘small, fast,

women, water and agile’ sports, disciplines and events since as early as the 1980s. This strategy

was predicated on the identification of the ‘Five-Word principle’ and Tian’s clustering theory

which categorised Olympic sports/disciplines into primarily physical-based (including sub-

categories of speed, explosive power and endurance) and primary skill-based (including sub-

categories of accuracy, difficult and artistic, net, non-net and combat) categories (Tian 1998).

The fruit has been that China has effectively identified and largely reinforced its niche markets,

which led to China’s rapid rise on the Summer Olympic stage. China’s longstanding dominance

in ‘small ball’ sports of table tennis and badminton, and lightweight divisions in weightlifting

echoes ‘small’, the substantial contributions of artistic gymnastics and diving resonate with

‘agile’ and China’s great success in diving also reflects China’s strategic targeting of ‘water’,

which is also evident in aforementioned 119 Project which emphasised all water sports.

Concerning ‘women’, female athletes have contributed to 56% of all gold medals and 58% of all

medals that China has won at the Summer Olympic Games. Female athletes outperform their

male counterparts in the most sports and disciplines. Appendix 1 summarises the gender-specific

medal contributions of all sports/disciplines to China at the Summer Olympic Games between

Los Angeles 1984 and Rio de Janeiro 2016.

25

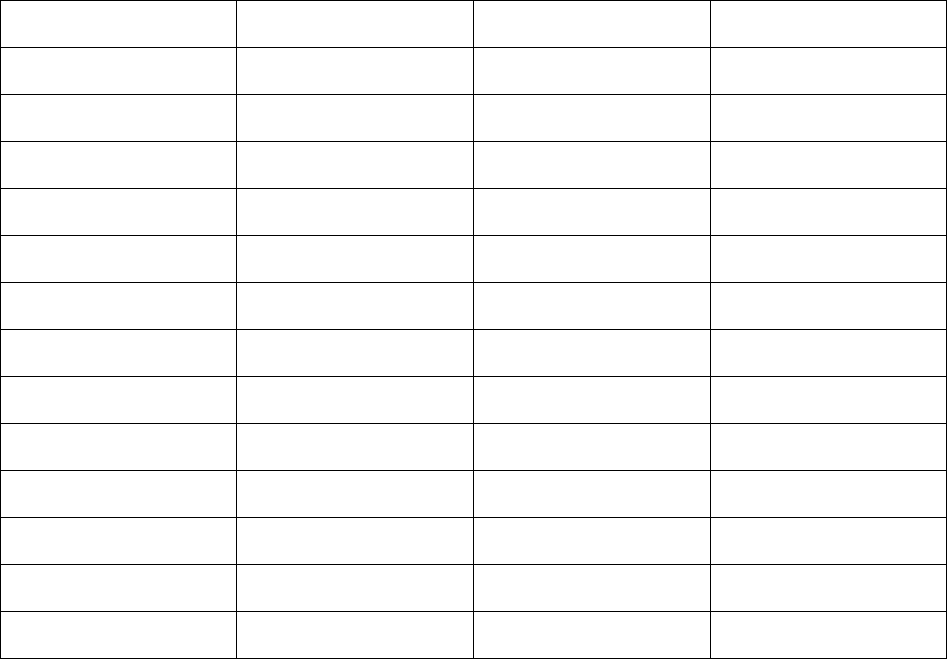

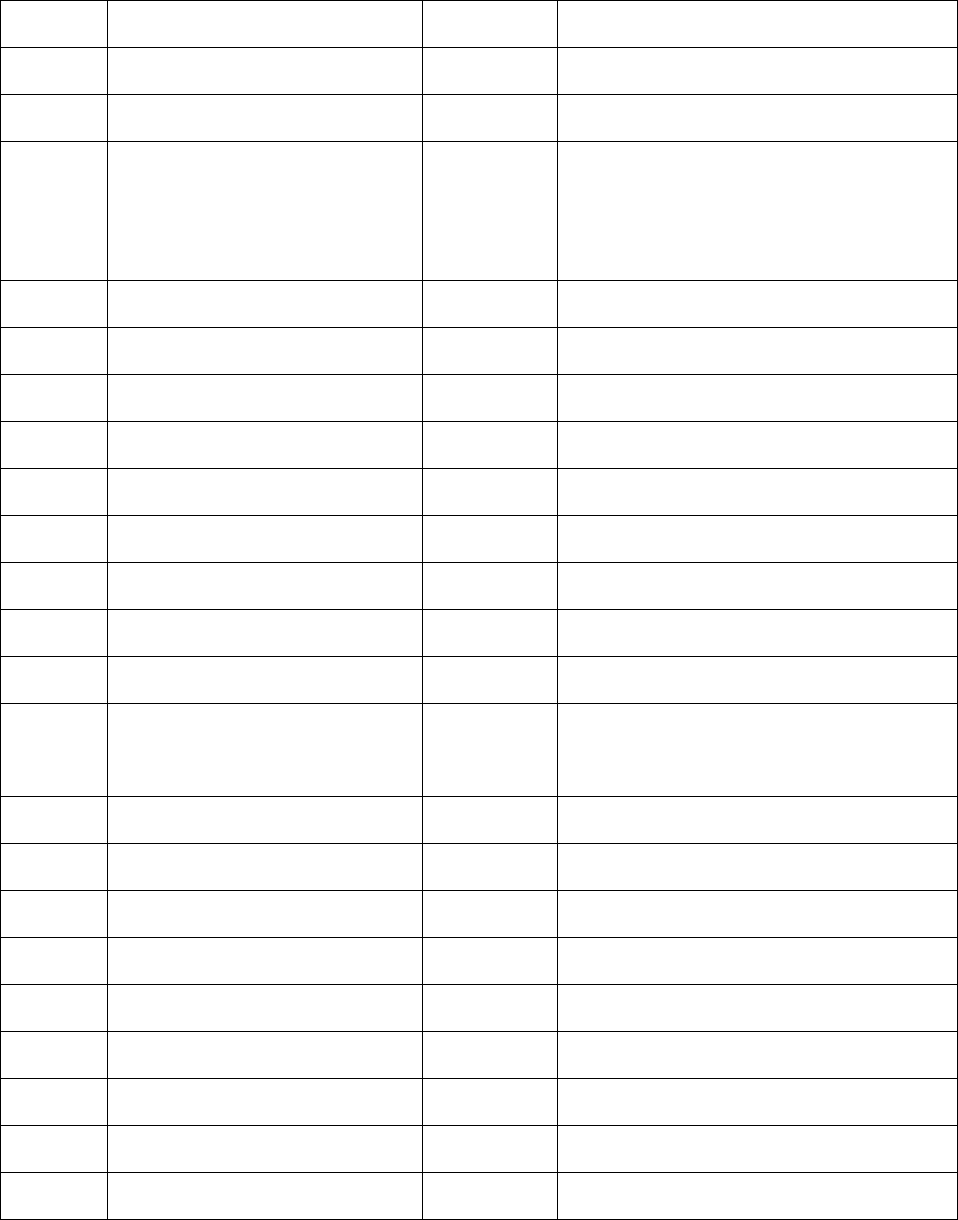

The impact of Tian’s (1998) clustering theory is also discernible. According to Table 5,

primarily skill-based sports/disciplines constitute the main source of China’s Olympic (gold)

medals (more than 70%), with the subcategories of difficult and artistic (for example, diving,

artistic gymnastics and trampoline) and net competition (table tennis, badminton, volleyball and

tennis) having contributed the most.

[Table 5 near here]

The strategic targeting and prioritisation is also evident in winter sports/disciplines. It is

apparent from Table 6 that short track speed skating contributed the bulk of gold medals won by

China, with the remaining medals coming from freestyle skiing, speed skating and figure skating.

11 out the total 12 gold medals come from ice-based sports/disciplines. China’s solitary

competitive advantage in snow-based competitions is freestyle skiing, which in combination with

figure skating, are the Winter Olympic manifestations of the principle of ‘agile’. Winter

sports/disciplines are a better illustration of the principle of ‘fast’ vis-à-vis their Summer

Olympic counterparts. This is illustrated by China’s high degree of competitiveness in short track

speed skating, and to a lesser extent, speed skating. The gender polarisation is more evident in

winter sports. Female athletes have won 10.5 out of the 12 gold medals, and accounted for 76.3 %

of all medals that China has won at the Winter Olympic Games. This is another illustration of

China’s deliberate targeting and prioritisation of female competitions.

[Table 6 near here]

26

However, China’s strategic targeting is confronted with issues most notably sustainability

and external threats. This combination has eroded China’s competitiveness, illustrated by

China’s sharp decline in gold medal tally at Rio de Janeiro 2016, overtaken by the UK in the

gold medal table. China’s traditional ‘markets’, most notably shooting (one gold in 2016), artistic

gymnastics (no gold in 2016 vs. four in 2012), and to a lesser extent, badminton (two in 2016 vs.

five in 2012) shrank significantly, while there was little progress, but more commonly,

deterioration in potential advantages (in swimming, fencing and women’s combat sports) and

lagging sports/disciplines. In fact, GAS realised the difficulty of maintaining or expanding

China’s advantage simply by relying on traditional sports which tend to be vulnerable to a wide

range of emerging nations’ ‘invasion’. Accordingly, the quality of (gold) medals in

internationally popular and mostly Western-dominated sports/disciplines was valued. This is

evident in the explicit policy objectives of enhancing China’s competitiveness in foundation

sports (athletics, swimming and other water sports of rowing, canoeing and sailing) and

collective ball sports most notably three ‘big ball’ sports (football, basketball and volleyball)

(GAS 2011a). There is some evidence of success, for example, in athletics and volleyball, but the

impact in most targeted sports/disciplines has not been discernible.

As a consequence of Beijing and Zhangjiakou’s successful bid to host the 2022 Winter

Olympic Games, it is projected that there will be a winter sports boom in China in the lead-up to

2022. The salience of and support for Winter Olympic sports/disciplines have already been

elevated, providing opportunities both for the further progress most notably gold medal winning

capabilities in traditional sports/disciplines, and for breakthroughs in a wide range of peripheral

sports, most notably snow-based sports/disciplines.

27

Emerging issues and debates

Resonating with the changing political and economic contexts of China in recent years, there are

many new trends in Chinese sport that have received considerable attention. Major issues include

(a) the balance amongst varying policy areas most notably between elite sport and sport for all;

(b) China’s ambitious SME strategy and the likely legacy; (c) the reform of sports governing

bodies, and the conflict between traditional bureaucratic modus operandi and professional and

market approaches; and (d) the development of sports commercialisation, professionalisation and

China’s increased and more proactive sports globalisation.

First, the balance between elite sport and mass sport or sport for all is a perennial issue in

China. Although elite sport has long been the overriding priority and the distribution of

government resources is biased in favour of elite sport, sport for all has received increased

government attention in recent years. If the National Fitness Programme published in 1995 was

largely rhetorical, then a succession of policy documents issued during Xi Jinping’s tenure,

including the No. 46 Document (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2014), the

No.37 document (The State Council of the People's Republic of China 2016) and the 13

th

Five

Year Plan for Sports Development in China (GAS, 2016) officially elevated the policy salience

of sport for all. The transformation of China’s national fitness policy, propelled by health

concerns most notably for young persons, serves as an integral part in the realisation of the

fundamental policy objective of shaping China into a world sports power.

However, in realising this policy objective, it seems that the Chinese government does

not plan to downgrade the support for elite sport. Although the support for mass sport has been

more substantial and the polarisation between elite sport and sport for all has been, to some

extent, reduced, the priority status of elite sport is secure because of its multiple political, social

28

and economic functions. In the near future, it is unlikely that the government will significantly

reduce its support for elite sport, in particular against the backdrop of China’s decline at Rio de

Janeiro 2016, the concerns for challenges at Tokyo 2020 and the approaching of the home

Winter Olympic Games in 2022 and a global trend that elite sport has become an ‘irresistible

priority’ (Houlihan 2011, p. 367) in many nations, including China’s direct competitors most

notably the UK and Japan. A more constructive solution would be to resolve the conflict between

elite sport and mass sport, and reconcile and balance their development, rather than downgrade

one to elevate another.

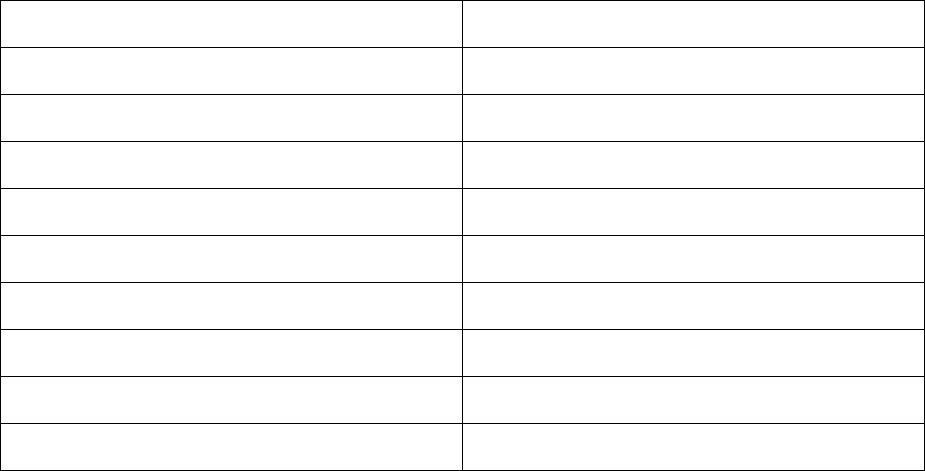

Hosting SMEs has been another main feature of Chinese sport in particular since the

2000s. This is particularly pertinent in showcasing China’s ‘soft power’ (Grix and Lee, 2013,

Nye 1990, 2008). In addition to China’s hosting of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games

and the forthcoming 2022 Winter Olympic Games in Beijing and Zhangjiakou, China has hosted

a series of SMEs such as the 1990 Beijing Asian Games, 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games, 2014

Nanjing Youth Olympic Games, and the World Championships of various Olympic sports and

disciplines including the 2011 Shanghai World Aquatics World Championships, the 2015

Beijing World Athletics Championships, and the country will host the 2019 FIBA Basketball

World Cup. There is a burgeoning of SMEs hosted in China in the last decade (see Table 7). In

addition, various internationally popular professional sports events have been attempting to

expand their influence and popularity in China. Notable examples include Shanghai Formula

One Grand Prix, NBA pre-seasonal tour in China, Italian Cup Final, and major events of tennis

and snooker. More recently, the Vice President and Secretary of the Chinese Football

Association (CFA) Zhang Jian (2017, quoted in Xinhuanet 2017) explicitly confirmed China’s

ambition to host the FIFA Men’s World Cup, which has already been stated as an ambition in the

29

fundamental No. 11 policy document of The Overall Plan for the Reform and Development of

Football in China (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2015).

[Table 7 near here]

The football reform made football one of the pioneer sports for the ‘substantiation’ (Liu

2008, p. 21), or ‘de-governmentalisation’ (Hu 2015) of Chinese sports. The CFA has been

undergoing a major reform to achieve a development pathway largely independent from the

government, and currently, football is the only Olympic sport in China which is governed by the

NSA, without a football-specific national management centre (GAS, 2017). In China, NSAs of

almost all Olympic sports/disciplines are just another brand of their corresponding national

sports management centres, and hence affiliated to GAS and governed by GAS officials.

However, despite the difficulty of avoiding actual government intervention in practice, the

independence reform of CFA is still a big step forward in sport in China, which is likely to spill

over to other sports most notably these having been professionalised in China. More recently, the

former NBA star Yao Ming, was appointed the President of the Chinese Basketball Association

(CBA) through election (NBA 2017). This differed from the direct appointment of some ‘insider’

officials within the machinery of Communist government. This attempt also involves the

development of alternative, or non-government forces in the participation of sport, in particular

elite sport in China transcending the traditional government-led Juguo Tizhi.

Despite the hyperbole that surrounds the arguments on the politicised and government-

dominant nature of the sport system in China, it is safe to say that previously, non-governmental

sectors, most notably private sectors were largely excluded from sport, particularly in relation to

30

elite sport. However, influenced by China’s increased pace of globalisation and the introduction

of commercialisation and professionalisation in sport, commercial elements, despite their

exclusion from decision-making, have become increasingly significant in sport development

through sponsorship, broadcasting and professional leagues organised most notably in football,

basketball and table tennis (Chen, Tan and Lee 2015, Houlihan, Tan and Green 2010, Tan and

Bairner 2010, 2011, Tan and Houlihan 2012).

In China, ‘sport is a field of both cultural and economic significance and hence has been

experiencing pressures to open its management up to market forces’ (Hu and Henry 2017, p. 2).

The number of internationally renowned football stars (for example, Didier Drogba, Carlos

Tevez and Graziano Pellè) and basketball stars (for example, Tracy McGrady, Stephon Marbury

and J. R. Smith) playing for Chinese clubs has exploded in the last five to ten years. In addition

to the establishment and development of professional leagues since the mid-1990s most notably

in football, basketball, table tennis, and volleyball, top female tennis players have been allowed

to achieve a high degree of independence from the control of the National Tennis Management

Centre and the Chinese Tennis Association, and to organise their own teams including coaches

and scientific support staff to participate in professional tours. However, the tentacles and

influence of market elements vary considerably amongst sports, and most non-popular and non-

professionalised sports still rely overwhelmingly on the traditional government-led model and

government funding (ifeng 2013). Furthermore, there is still a clash between the emerging

commercial and the traditional bureaucratic elements even in the relatively more professionalised

sports such as football and basketball. Government order and administrative intervention are still

prevalent in these sports, illustrated by the most recent case of the CFA’s new rule that the

31

number of foreign athletes each club sent on pitch should equalise that of under-23 players in a

match (People.cn 2017).

Last, China has become more proactive in sports globalisation, evolving from an

importing to an exporting country. Notable examples included Chinese entrepreneurs’ recent

purchase of internationally renowned football clubs such as Inter Milan and AC Milan. Chinese

companies’ sponsoring of and investment in foreign clubs and international organisations has

also become more pervasive, facilitated by China’s rapid economic growth in the last ten to 15

years.

Conclusions

Sport has consistently been an important government responsibility in PR China, with

specialised government departments at the central level and substantial financial support, with

the only exception of the turbulent time of the Cultural Revolution. Its policy significance has

been further raised in recent decades, commensurate with the rapid development of sport in

China, ranging from elite sport success, the hosting of SMEs, to China’s increased global sports

participation and the ever-growing professionalisation, and policies regarding sport for all.

However, China is confronted with a series of issues and challenges in sport development.

Elite sport has long been the overriding priority in China, and China’s notable success

has been underpinned by effective policy and strategic approaches. However, elite sport in China

is confronted with several challenges in the modern era, ranging from the sustainability of

China’s traditional advantages and the enhancement in the competiveness in non-traditional

sports, to the ever-changing global environment and increasingly intense global competition, the

need to expand China’s sources of advantages in Winter Olympic sports and disciplines, and the

32

increasing concern with mass sport and other sports areas. Many of these issues have been stated

in the latest policy documents, but it remains challenging to implement effective policies.

Mass sport seems to welcome a new era of development in China, because of various

political, cultural and social factors mentioned above. The increased public demand for and

government emphasis on mass sport, instead of clashing with China’s traditional focus on elite

sport, should be effectively synergised with elite sport success. How to drive mass participation

and raise the awareness and passion for a healthy lifestyle amongst the general public through

the trickle-down effects of elite sport success, and how to expand the talent base for elite sport

development may be important in realising a balance, and more importantly, developing a

synergy between these two prominent sport areas.

Sport professionalisation, globalisation, and the burgeoning hosting opportunities of

SMEs are relatively new features of Chinese sport, resonating with China’s increased wealth,

globalisation process and elevated political ambition. However, the relic of bureaucratic

elements, in particular ‘planned economy’ elements, thoughts and approaches, are likely to

constrain the further development of these new phenomena. A notable example would be the

clashes between traditional government-led governing system and its concomitant political

intervention, and the professionalisation process of some sports. The reform of the organisational

structure particularly ‘de-governmentalisation’ has been put in place, but it is still in its relative

infancy. For the hosting of SMEs, to create a sustainable legacy to benefit the general public is

what the government may need to consider.

In the foreseeable future, it is projected that sport will remain a significant government

concern, and both opportunities and challenges will befall Chinese sport. Although some of these

may be more evident in China, the nation is not immune from some common themes of sport

33

development on a global scale, for example, the balance between various aspects, the need to

realise the full potential of sport in benefiting the public, and sport globalisation.

Notes

1. These ten sports were: athletics, basketball, gymnastics, volleyball, table tennis, football,

weightlifting, swimming, skating and shooting (Hong 2011).

34

References

Administration of Sports of Guangzhou Municipality, 2006. Commercial promotion campaign of

the 2006 World Wrestling Championships [online]. Available from:

http://www.gzsports.gov.cn/info/1527/2962.htm [Accessed 9 June 2016].

Badminton World Federation (BWF), 2013. 2013 BWF World Championships [online].

Available from: http://www.bwfbadminton.org/page.aspx?id=23535 [Accessed 9 June

2016].

Brownell, S., 2005. Challenged America: China and America – women and sport, past, present

and future. The international journal of the history of sport, 22 (6), 1173-1193. doi:

10.1080/09523360500286817.

Cao, X. and Brownell, S., 1996. The People’s Republic of China. In: L. Chalip, A. Johnson and

L. Stachura, eds. National sports policies: an international handbook. London and

Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 67-88.

Chen, X. and Chen, S., 2016. Youth sport in China. In: K. Green and A. Smith, eds. Routledge

handbook of youth sport. Abingdon: Routledge, 131-141.

Chen, Y.W., Tan, T.C. and Lee, P.C., 2015. The Chinese government and the globalization of

table tennis: a case study in local responses to globalization of sport. The international

journal of the history of sport, 32 (10), 1336-1348. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2015.1036239.

Chow, G.C., 2001. The impact of joining WTO on China’s economic, legal and political

institutions. Invited speech during the International Conference on Greater China and the

WTO, March 22-24, 2001, organised by the City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Dai, Y., 2009. A study on the ‘whole country support for elite sport system’ after the 2008

Beijing Olympic Games (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis). Shanghai University of Sport, China.

35

Dai, G., Shao, C. and Bao, C., 2011. The impact of sports policy in differentperiods in China on

sport. Shi ji qiao, 7, 107-108.

Dong, J., 1998. A reflection on ‘factors determining the recent success of Chinese women in

international sport’. The international journal of the history of sport, 15 (1), 206-210. doi:

10.1080/09523369808714021.

Dong, J., and Mangan, A., 2008. Olympic aspirations: Chinese women on top – considerations

and consequences. The international journal of the history of sport, 25 (7), 779-806. doi:

10.1080/09523360802009180.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2002. 2001-2010 nian aoyun zhengguang jihua

gangyao [The outline of the strategic Olympic glory plan: 2001-2010]. Beijing: GAS.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2003. 2008 Nian aoyun zhengguang xingdong jihua

[The 2008 Olympic glory action plan]. Beijing: GAS.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2006. Tiyu fazhan 'shiyiwu' guihua [The 11th Five-

year plan for sports development in China] [No.26]. Beijing: GAS.

General Administration of Sport of China (GAS), ed. 2009. A hard-fighting journey and

brilliant achievements: A sixty-year history of Sport in New China (Comprehensive

Volume). Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2011a. 2011-2020 nian aoyun zhengguang jihua

gangyao [The outline of the strategic Olympic glory plan: 2011-2020]. Beijing: GAS.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2011b. Tiyu fazhan ‘shiserwu’guihua [The 12th Five-

Year plan for sports development in China]. Beijing: GAS.

General Administration of Sport (GAS), 2016. Tiyu fazhan ‘shisanwu’ guihua [The 13th Five-

Year plan for sports development in China]. Beijing: GAS.

36

General Administration of Sport of China (GAS), 2017. Units directly under the General

Administration of Sport of China [online]. Available from:

http://www.sport.gov.cn/n16/n33193/n33223/index.html [Accessed 25 May 2017].

Grix, J. and Lee, D., 2013. Soft power, sports mega-events and emerging states: the lure of the

politics of attraction. Global society, 27 (4), 521-536. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2013.827632.

Hong, F., 1998. The Olympic movement in China: ideals, realities and ambitions. Culture, sport,

society: Cultures, commerce, media, politics, 1 (1), 149-168. doi:

10.1080/14610989808721805.

Hong, F., 2008. China. In: B. Houlihan and M. Green, eds. Comparative elite sport development:

systems, structures and public policy. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 26-52.

Hong, F., 2011. Sports development and elite athletes in China. In: B. Houlihan and M. Green

eds. Routledge handbook of sports development. Abingdon: Routledge, 399-417.

Hong, F. and Lu, Z., 2012a. Representing the New China and the Sovietisation of Chinese sport

(1949-1962). The international journal of the history of sport, 29 (1), 1-29. doi:

10.1080/09523367.2012.634982.

Hong, F. and Lu, Z., 2012b. From Barcelona to Athens (1992-2004): ‘Juguo Tizhi’ and China’s

quest for global power and Olympic glory. The international journal of the history of

sport, 29 (1), 113-131. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2012.634987.

Hong, F. and Lu, Z., 2012c. Beijing’s two bids for the Olympics: the political games. The

international journal of the history of sport, 29 (1), 145-156. doi:

10.1080/09523367.2012.634989.

37

Hong, F., Wu, P. and Xiong, H., 2005. Beijing ambitions: an analysis of the Chinese elite sports

system and its Olympic strategy for the 2008 Olympic Games. The international journal of

the history of sport, 22 (4), 510-529. doi: 10.1080/09523360500126336.

Houlihan, B., 2011. Sports development and elite athletes – introduction: the irresistible

priority. In: B. Houlihan and Green, M, eds. Routledge handbook of sports development.

Abingdon: Routledge: 367-370.

Houlihan, B., Tan, T.C. and Green, M., 2010. Policy transfer and learning from the West: elite

basketball development in the People’s Republic of China. Journal of sport and social

issues, 34 (1), 4-28. doi: 10.1177/0193723509358971.

Hu, X., 2015a. An Analysis of Chinese Olympic and Elite Sport Policy Discourse in the

Post-Beijing 2008 Olympic Games Era (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis). Loughborough

University, UK.

Hu, X., 2015b. Chinese football and its number one fan: the political influence on China’s

emerging interest and new moves in football (Asia & the Pacific Policy Society: policy

forum) [online]. Available from: https://www.policyforum.net/chinese-football-and-its-

number-one-fan/ [Accessed 24 August 2017].

Hu, X. and Henry, I., 2016. The development of the Olympic narrative in Chinese elite sport

discourse from its first successful olympic bid to the post-Beijing Games era. The

international journal of the history of sport, 33 (12), 1427-1448. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1284818.

Hu, X. and Henry, I., 2017. Reform and maintenance of Juguo Tizhi: governmental

management discourse of Chinese elite sport. European sport management quarterly, 1-23.

doi: 10.1080/16184742.2017.1304433.

38

Hubei Administration of Sport, 2013. Gymnastics Management Centre of Hubei Administration

of Sport [online]. Available from:

http://www.hbsport.gov.cn/html/view/Units/ticaozhongxin/ [Accessed 10 July 2013].

ifeng, 2009. A sixty-year journey of pursuing dreams: sport history of People’s Republic of

China (1949-2009) [online]. Available from: http://sports.ifeng.com/zhuanti/sports60/#002

[Accessed 28 October 2017].

ifeng, 2013. The road to professionalisation of main sports in China [online]. Available from:

http://news.ifeng.com/gundong/detail_2013_07/08/27238235_0.shtml [Accessed 24

August 2017].

ifeng, 2017a. Leadership changes of GAS: Li Yongbo, Wang Yifu and Huang Yubin were all

relieved of their offices [online]. Available from: http://v.ifeng.com/video_6890433.shtml

[Accessed 23 May 23 2017].

ifeng, 2017b. The former Secretary General of the Chinese Olympic Committee Jizhong Wei:

there should be more discussions rather than debates on sprots reform in China [online].

Available from: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20170802/51551379_0.shtml [Accessed 24

August 2017].

International Association of Athletics Federation (IAAF), 2016. Previous event: 15th IAAF

World Championships [online]. Available from:

http://www.iaaf.org/competitions/iaaf-world-championships/15th-

iaaf-world-championships-4875 [Accessed 9 June 2016].

39

International Basketball Federation (FIBA), 2015. PR N°30 - People's Republic of China to host

2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup [online]. Available from:

http://www.fiba.com/pr-n30-peoples-republic-of-china-to-host-2019-fiba-

basketball-world-cup [Accessed 12 June 2016].

International Boxing Association (AIBA), 2016. Men's World Champions [online]. Available

from: http://aiba.s3.amazonaws.com/2015/02/AIBA-World-Champs-74-05-.pdf [Accessed

9 June 2016].

International Gymnastics Federation (FIG), 2016. About men's artistic: World Championships

[online]. Available from: http://fig-gymnastics.com/site/page/view?id=392 [Accessed 29

April 2016].

International Handball Federation (IHF), 2016. Women's World Championships: previous

Women's World Champions – indoor [online]. Available from: http://www.ihf.info/en-us/

ihfcompetitions/competitionsarchive/womenworldchampionships.aspx [Accessed 9 June

2016].

International Olympic Committee (IOC), 2016. Nanjing 2014 [online]. Available from:

https://www.olympic.org/nanjing-2014 [Accessed 9 June 2016].

International Olympic Committee (IOC), 2017a. Olympic Games [online]. Available from:

https://www.olympic.org/olympic-games [Accessed 25 May 2017].

International Olympic Committee (IOC), 2017b. Results [online]. Available from:

https://www.olympic.org/olympic-results [Accessed 29 May 2017].

International Softball Federation (ISF), 2006. USA wins 2006 Women's World Championship

[online]. Available from: http://www.isfsoftball.org/english/events/06_09_05_wwc.asp

[Accessed 9 June 2016].

40

International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), 2016. ITTF events [online]. Available from:

http://www.ittf.com/competitions/competition.asp?category=wttc [Accessed 9 June 2016].

International University Sports Federation (FISU), 2016. FISU history [online]. Available from:

http://www.fisu.net/en/FISU-history-3171.html [Accessed 9 June 2016].

Jarvie, G., Hwang, D.J. and Brennan, M., 2008. Sport, revolution and the Beijing Olympics.

Oxford: Berg.

Johnson, W., 1973. Faces on a New China scroll. Sports illustrated, 13, 82-100.

Li, F., 2000. Li Furong’s speech on how to become an outstanding coach. China sports daily,

12 (4), 2.

Li, Z., 2008. A review of the reform of Management Centres of the General Administration of

Sport of China. Sports culture guide, 26 (4), 3-7.

Li, Q. and Zhou, Y., 2012. Research on the status quo and development antidotes of national

sports associations of indivudual sports in China. Journal of Beijing Sport University,

35 (12), 29-34.

Liang, X., Bao, M. and Zhang, L., 2006. ‘Juguo Tizhi’ (Whole country support for the elite sport

system). Beijing: People’s Sports Publishing House of China.

Lin, S., 2006. From fragmentation to coordination – the policy growth of mass and elite sports in

China. Journal of Anhui Science and Technology University, 20 (1), 59-62.

Liu, D., 2008. Evolution and contemplation of the reform to substantiate single sport associations

in China. Journal of physical education, 15 (9), 21-25.

Liu, D. and Zhang, L., 2008. Research on marketing development and fund-raising mechanism

of China’s National Sport Associations. China sport science, 28 (2), 29-36.

41

National Basketball Association (NBA), 2017. Former Houston Rockets star Yao Ming named

president of Chinese Basketball Association [online]. Available from:

http://www.nba.com/article/2017/02/23/yao-ming-named-president-chinese-basketball-

association [Accessed 23 March 2017].

Nye, J.S., 1990. Bound to lead: the changing nature of American power. New York, NY:

Basic Books.

Nye, J.S., 2008. Public diplomacy and soft power. The annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science, 616 (1), 94-109. doi: 10.1177/0002716207311699.

Olympic Council of Asia (OCA), 2016a. Games: Asian Games [online]. Available from:

http://www.ocasia.org/Game/GamesL1.aspx?9QoyD9QEWPeJ2ChZBk5tvA== [Accessed

9 June 2016].

Olympic Council of Asia (OCA), 2016b. OCA praises Hangzhou Asian Games following

conclusion of two-day visit [online]. Availabel from:

http://www.ocasia.org/News/IndexNewsRM.aspx?WKegervtea1wqBRlBoiHRA==

[Accessed 26 May 2017].

Pan, J., 2012. A study on the management system of the ‘government-led’ elite sport system in

China and its operation mechanism (Unpublished MSc dissertation). East China Normal

University, China.

Peope.cn, 2015. The major sports nation needs to develop winter sports: the goal of ‘getting a

population of 300 million in China involved in winter sports’ is not utopian [online].

Available from: http://sports.people.com.cn/n/2015/0216/c22176-26574831.html

[Accessed 25 May 2017].

42

People.cn, 2017. The CSA’s new policy spawned wide debate: the regularities of football

development have to be understood [online]. Available from:

http://sports.people.com.cn/n1/2017/0526/c22134-29301006.html [Accessed 27 May

2017].

Rong, G., ed. 1987. The history of contemporary Chineses sport. Beijing: China Social

Sciences Publishing House.

Shanghai 2011, 2011. 14

th

FINA World Championships – Shanghai 2011 [online]. Available

from: http://www.shanghai-fina2011.com/en/ [Accessed 9 June 2016].

Sports Commission of China, 1995. 1994-2000 nian aoyun zhengguang jihua gangyao [The

outline of the strategic Olympic glory plan: 1994-2000]. Beijing: Sports Commission of

China.

Sports.cn, 2007. 2007 Beijing Taekwondo World Championships [online]. Available from:

http://zhuanti.sports.cn/07taekwondo/index.html [Accessed 9 June 2016].

Sports-Reference, 2017. Olympic countries: China – winter sports [online]. Available from:

http://www.sports-reference.com/olympics/countries/CHN/winter/ [Accessed 26 May 26

2017].

Tan, T.C., 2015. The transformation of China's national fitness policy: from a major sports